Slack Technologies, the developer of the popular namesake team collaboration messaging app, recently applied for a public offering on the stock market. This is not a classic IPO, but a “direct listing,” also known a “direct public offering.” This means Slack is not raising money by directly selling shares and instead allows early investors and employees to sell their shares in the public offering. Music streaming service Spotify held a successful direct listing last year.

This story caught my attention for a simple reason. In August 2016, I joined the team developing a still-undercover product called Workplace by Facebook—a direct competitor to Slack. I worked on the product for 2.5 years. Back then, I dreamed of having an opportunity to look inside Slack’s business metrics.

It may seem that Slack has revealed a lot of data about the business in their S-1 filing, a document that is almost 200 pages in length.

The reality is, they haven’t. The company had already disclosed in various ways much of the information compiled in their report.

But if we combine the data disclosed in S-1 filing and the experience I gained while working on Slack’s competitor, we’ll be able to uncover interesting details that will paint a more holistic picture.

I must say that this article contains my personal thoughts on the matter, jotted down while going through their S-1 filing, and should not be considered as investment advice.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

Slack’s top-level business metrics

- Slack doubles its revenue every year: $105.1M, $220.5M, $400.5M (respectively from 2016, 2017, 2019).

- Gross margin remains at the level of 87-88%. This doesn’t sound bad at all, although it isn’t unexpected from a fully digital product that costs several times more than its direct competitors.

- There is a lot of talk in the press about Slack’s unprofitability; the company shows a net loss of about $140M per year. But if we take a look at the cost structure and growth drivers (we’ll get to this later), then the losses won’t look like a problem. You can read more about this here.

- Slack estimates the market opportunity of workplace business technology software communication platforms at $28B per year. My own evaluation of the market stands at about the same number.

- Slack’s S-1 reminds us of the true costs of venture capital. The founders are left with 8.6% and 3.4% of the company. Meanwhile, the biggest shareholders are VC firms Accel Partners (24%), Andreessen Horowitz (13.3%), and Softbank (7.3%).

Number of free and paid Slack customers

- Approximately 588,000 organizations use Slack.

- However, the concept of “organization” is rather vague in the report: “We define an organization on Slack as a separate entity, such as a company, educational or government institution, or distinct business unit of a company, that is on a subscription plan, whether free or paid. Once an organization has three or more users on a paid subscription plan, we count them as a Paid Customer.” So, if there are 15 IBM teams using Slack, does it count as one organization or 15? It’s not clear.

- 88,000 of these organizations are paid customers, and over 500,000 organizations use Slack’s free subscription plan.

- Therefore, 15% of the active organizations are paying for the service. But this doesn’t give us a lot of information. Imagine 100 new companies register with Slack, but 99 of them stop using it after a while, and one remaining company purchases one of Slack’s paid plans. In this case we can say 100% of active companies are paid customers. But looking at it from a different perspective, only 1% of new companies become paid customers.

- My assessment of a long-term retention rate from a new organization into an active one for Slack is 5–10%. This is a very rough estimate. Moreover, long-term retention rates differ greatly depending on industry and acquisition channel.

- This estimation is based on my personal experience and the following quote from an old interview with Slack’s founder: “Most people who fill out the form and hit submit — more than 90% — never invite anyone or start using the software.”

- If this estimation is correct, then 588,000 active organizations indicate that 5.5–11 million new organizations joined Slack over the service’s entire lifetime. This means that Slack gets about 115-230k new leads per month.

- If the estimate of the total number of organizations is correct, then the conversion rate from a new organization into a long-term paying customer stands at around 0.8-1.6%. If we factor in the average churn for SaaS (approx. 50% of new customer will churn over the first year), then the conversion rate from a new organization signing up with Slack into the one that pays at least once will stand at around 1.5-3.5%.

- In many ways, Slack’s cleverness is hidden behind its strong brand and a huge flow of new organic leads. We will talk about it further on.

Slack’s user engagement

- Slack’s DAU stays at around 10 million users (these are the users who either created or consumed content in the service at least once in 24 hours). The dynamics of DAU looks impressive.

- Slack had previously revealed its overall DAU and DAU of its paying users. But in the S-1 filing, it only mentions the overall DAU. This might signal that the growth of paying users has slowed down. Overall revenue growth is being pulled out by raising prices through the introduction of new tariffs and Slack for Enterprise taking a greater share of the revenue of the service.

- More than 1 billion messages are sent via Slack every week. This means that the average active user sends 14 messages per day. This is a good level of user engagement, but it’s not extraordinary or impressive.

- An average active user spends 42 minutes per day in the service. In comparison, active paid users spend an average 90 minutes in Slack per working day. These numbers don’t look bad. But when compared to the average 14 messages sent per user, they look dubious.

- The big question is, how does Slack calculate time spent in the product? A few years ago, they simply looked at the time the service was active on users’ devices. That has changed, but the company mentions no specific methodology in their filing, which makes it difficult to interpret the numbers.

Slack’s business model

Even without a report, Slack’s business model seems obvious, but the company laid it out eloquently in the filing:

“We offer a self-service approach, for both free and paid subscriptions to Slack, which capitalizes on strong word-of-mouth adoption and customer love for our brand. Since 2016, we have augmented our approach with a direct sales force and customer success professionals who are focused on driving successful adoption and expansion within organizations, whether on a free or paid subscription plan.”

Here are the key points:

- Slack gets most new customers organically through word-of-mouth(self-serve model).

- Some of the new organizations convert into paying customers.

- The sales team works with leads that qualify as large organizations.

- The goal of the sales team is to increase Slack’s penetration within large organizations.

Let us now reflect on some of these points in more detail.

The top of Slack’s funnel is driven by organic signups from word-of-mouth

“We offer a self-service approach, for both free and paid subscriptions to Slack, which capitalizes on strong word-of-mouth adoption and customer love for our brand.”

The first question that occurs after reading this sentence is, why doesn’t Slack accelerate growth by investing in acquisition through paid ad channels? It isn’t hard to verify that Slack almost doesn’t invest in Google Ads or Facebook Ads (there are some paid ads, but they’re mostly focused on branded search).

Here’s the short answer: The SMB (small and medium-sized business) segment’s economics doesn’t justify paying for ads because the return on investment is negative (ROI < 0). Meanwhile, direct advertising channels don’t work for the enterprise segment.

Now here’s a more detailed answer:

- The average cheque for Slack’s paying customers is $380 per month.

- If we ignore companies that Slack considers as enterprise customers (with more than $100k ARR), then the average cheque per month will be $230, and the average organization’s size will be 40 people.

- Thus, a self-serve client brings ~$2,760 in revenue in the first year and ~$2,400 in gross profit in the first year.

- If the goal is to get a positive return on investment (ROI) within 12 months, then, then a long-term paying client should cost $2,400 in the self-serve segment.

- With a 0.8-1.6% conversion rate into a long-term paying customer, a new organization should cost $20-40.

- But in B2B, leads from organic channels usually demonstrate 2-4 times better metrics than the leads from paid advertising channels. Let’s assume that in the case of Slack, the difference is 2x. This means in order to get ROI > 0, Slack needs to acquire new organizations at a cost of $10-20.

- This looks unrealistic if we consider the economics of paid advertising channels in developed markets, where the average cost of a new organization from Google Ads or Facebook Ads will be around $100-200.

- That’s why Slack invests nearly nothing in paid acquisition. It grows mainly through strong brand, word-of-mouth, integrations with other services and the subsequent cross-promos, the professional communities in Slack and tools for communication between companies.

On the one hand, Slack is shielded from competitors because it has a huge number of organic leads and due to the fact that paid acquisition doesn’t work in the market, it is nearly impossible to get close to Slack in the self-serve segment.

On the other hand, as you will soon see, the self-serve segment acts as a gateway to reach enterprise customers. But Slack’s competitors have other ways to reach these companies.

Net Dollar Retention Rate is the most interesting piece of data Slack revealed

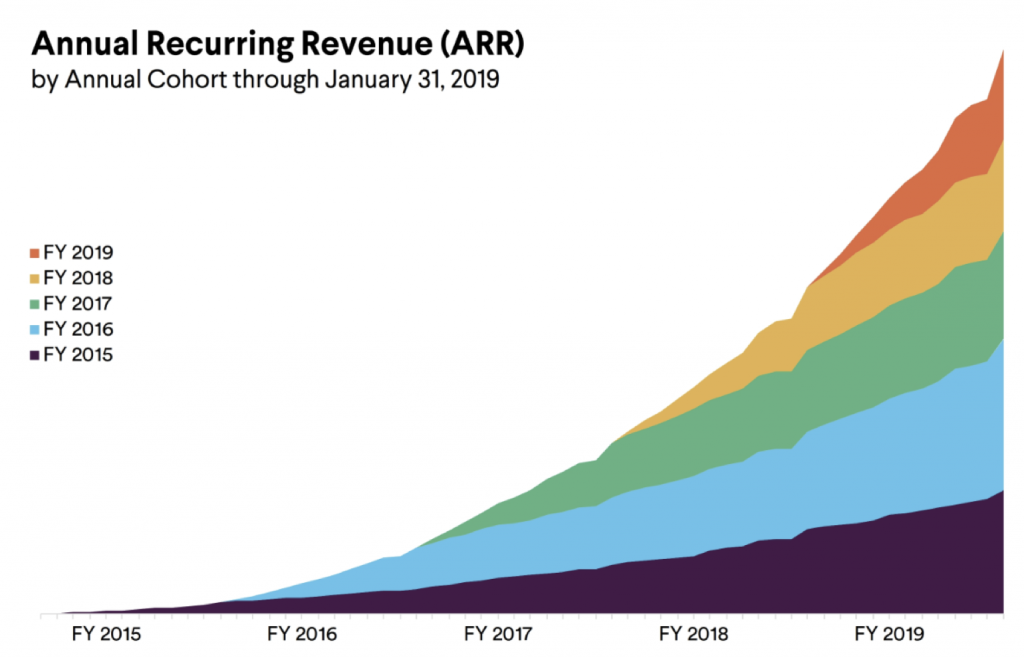

The following chart shows the growth of ARR (Annual Recurring Revenue) by cohorts based on the year when organizations first paid for using Slack.

ARR from organizations that first paid for Slack in 2015 continues to grow steadily in the following years.

For most products, cohorts shrink as they age. But in Slack’s case, we’re witnessing the opposite (this is also called Negative Revenue Churn). This is one of the main reasons why Slack is worth so much ($7B valuation at the latest funding round, $10B proposed valuation for the public offering).

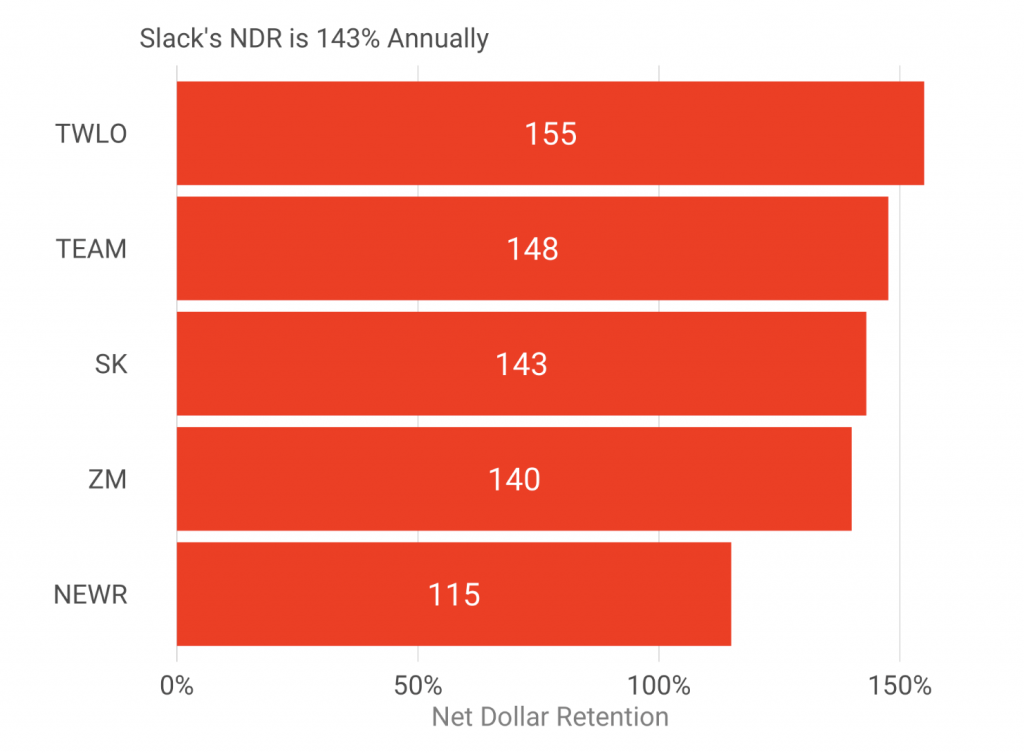

However, it is worth noting that such growth patterns are typical for products in this kind of market. Zoom, which recently went public, has a Net Dollar Retention of 140%. Twilio and Atlassian showed even more impressive figures at the time of their IPO (source).

The following are the main growth drivers:

- Expansion of the user base within companies that are already using the service: Slack is building up their sales team, which reaches out to companies that have already started using Slack, and does everything to get the remaining employees to switch to the service.

- The organic growth of customers: Companies that have started using Slack are hiring new employees and growing in size. More employees -> more Slack users -> Slack gets more money.

- Price changes: Slack raises prices directly or by introducing new tariff plans.

An interesting consequence here is that Slack’s growth depends more on how the team is developing the product and the growth of its current customers than on attracting new users and converting them into paying ones.

Acquisition, of course, is just as much important, but it has a rather delayed impact on the overall revenue growth.

Another consequence is that such growth mechanism depends greatly on having enough enterprise customers with many employees who have not yet started using Slack (it will be difficult to grow revenue from of old cohorts if all of them are SMBs with 40 employees).

If you look at the growth of new paying customers, it doesn’t look promising. Slack added 22,000 paying customers in 2017 and 29,000 in 2018. This is a 30% increase in new paying clients, but still not the kind of dynamics Slack would like to see.

Therefore, the main driver of Slack’s exponential revenue growth is the expansion of cash flow from its old customers.

Slack measures this process using the Net Dollar Retention Rate metric: They take all the customers who were already paying 12 months ago. They then divide the current MRR (Monthly Recurring Revenue) by the MRR for the previous 12 months.

Net Dollar Retention Rate for the last three years looks like this: 171%, 152%, 143%. That is, customers who paid a year ago pay much more in the following year. Which is fantastic. Net Dollar Retention Rate is gradually decreasing, but this is expectable due to the slowdown of growth in old cohorts.

Here’s what Slack’s report says about this:

“We disclose Net Dollar Retention Rate as a supplemental measure of our organic revenue growth. We believe Net Dollar Retention Rate is an important metric that provides insight into the long-term value of our subscription agreements and our ability to retain, and grow revenue from, our Paid Customers.

We calculate Net Dollar Retention Rate as of a period end by starting with the MRR from all Paid Customers as of twelve months prior to such period end, or Prior Period MRR. We then calculate the MRR from these same Paid Customers as of the current period end, or Current Period MRR. Current Period MRR includes expansion within Paid Customers and is net of contraction or attrition over the trailing twelve months, but excludes revenue from new Paid Customers in the current period, including those organizations that were only on Free subscription plans in the prior period and converted to paid subscription plans during the current period. We then divide the total Current Period MRR by the total Prior Period MRR to arrive at our Net Dollar Retention Rate.”

Enterprise is a problematic segment for Slack

If you have enough patience to go through the entire 200-page report, you will notice Slack repeatedly showcasing its success in the enterprise segment. This segment accounts for a significant part of the market ($28 billion spent on communication tools each year), and this is what Slack is striving for. This is the where their long-term growth lies and where they are getting Net dollar retention rate > 100%.

Here’s what the report says about this segment:

- Customers should have ARR > 100k to be considered enterprise customers.

- The number of enterprise clients in the past three years: 135, 298, 575

- The revenue share of the Enterprise segment in the past three years: 22%, 32%, 40%

- Revenue from enterprise customers over the past three years: $23M, $70.5M, $160.2M

- Average monthly spending by enterprise customers in the past three years: $14,200, $19,700, $23,200

- The largest customers have “tens of thousands of employees” or tens of thousands of active users per day—quite an ambiguous wording (“our largest Paid Customers have tens of thousands of employees using Slack on a daily basis”).

- For the last two years, almost all of the Slack product releases have been aimed at adapting the product to large organizations. Take for example Slack Enterprise Grid, adding Threads, Unread section.

At first glance, it does look impressive. But let’s take a closer look.

- Customers should have ARR > 100k to be considered enterprise customers. This means that organizations with over 1,000 employees using Slack fall into the enterprise segment. This is a rather low threshold. I assume it was chosen to get a larger absolute value of enterprise customers.

- Even with such a low threshold, Slack only has 575 enterprise clients. It is not much. Even Facebook Workplace, which entered the market much later (and doesn’t have such a phenomenal influx of organic leads), announced three months ago that it has 150 companies with more than 10,000 employees on the platform (source). And Teams, Microsoft’s Slack competitor, which launched even later than Workplace, has also achieved similar figures (source).

- Another way to look at 575 Enterprise customers is to compare it to the total number of organizations that have created a Slack workspace (5.5 – 11 million). Only 0.01% of them achieve enterprise status. Slack is very skewed towards the SMB segment, which suffers from a high churn rate and has very little potential for expanding revenue from its old customers.

- Major customers have tens of thousands of employees. It sounds impressive, but those who have worked with products focused on the enterprise segment know that there are many companies in the world with hundreds of thousands—and even millions—of employees (and usually they are outside the technology sector). A few examples of Facebook Workplace’s customers are Walmart, with 2.2 million employees, Starbucks with 250,000 employees, and Telenor with 37,000 employees (source). In terms of revenue, onboarding Walmart equates to signing up thousands of companies with 1,000 employees. This is not an attempt to say that Workplace rocks, but rather to mention that Slack finds it difficult to strike big deals.

- For the last two years, almost all of Slack’s product releases have been aimed at adapting the service to large organizations. This is true, but Slack doesn’t do it for fun. Slack loses most of its deals to competitors when trying to sign up enterprise clients, because the service works poorly for companies with over 500 employees, and even worse for companies scattered across different time zones. Synchronous communication, which is Slack’s forte, starts to falter under such conditions.

- And now regarding the blind spots that Slack was silent about in the report. The report has no clear breakdown of Slack’s customers by industry. This is an important question, since Slack initially grew in the IT and media segments. And it is unclear whether they managed to step beyond these limits, and how the product performs in more classical verticals (e.g. banking, retail, insurance, etc.). If Slack experiences problems there (as it previously has), then the market of $28B will be dramatically narrowed down to the niche of the technology business, which isn’t very impressive.

And here’s where things get really problematic for Slack:

- Microsoft already has access to a lot of large enterprise clients from all verticals and has been selling them products bundled in a single package for a long time. They recently added Microsoft Teams to the Office Suite, which is just as good as Slack in terms of functionality. Does Slack offer enough incentive to convince enterprise customers to forgo the benefits of their long-term relationship with Microsoft?

- Workplace by Facebook was originally designed for large organizations and outperforms Slack product-wise in this market segment. Moreover, Workplace works great outside the technology sector too because the product’s interface is very familiar to the masses, which means companies save a lot of money and time since they don’t need to do any employee training.

In the next 5-7 years (indeed, B2B and especially the enterprise sector are slow-paced markets with one of the longest transaction cycles) it will be thrilling to see how Slack responds to these threats and challenges.

Summing it up

- Well done for Slack. They won over the self-serve market segment and no one even comes close to them.

- Just as much as Slack enjoys its growth in the self-serve segment, they make the best out of it using it as a source of enterprise leads for the sales team, which then spreads Slack inside large corporations.

- Slack is growing rapidly and will continue to do so in the next few years (mostly due to the expansion of revenue coming from the old cohorts). However, what happens next is still a big question.

- Slack’s long-term growth depends on how much of the enterprise segment they’ll be able to conquer, and whether they’ll be able (or perhaps they already have – this is not clear from the report) to expand beyond the segment of tech companies.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.