Classical economics is built on the assumption that people act rationally, which means their decisions are aimed at maximizing their benefits. This statement (which is a base for the classic economics theory), is a bit doubtful, partly because people usually don’t have all the necessary information to make the best decision in a given situation. But even within the framework of the available information, people tend to make irrational decisions.

In this post I will show you some interesting experiments that highlight relevant characteristics and patterns in humans’ decision making processes. Most of these experiments are about the way people behave when deciding about purchasing something, so you can easily apply them to your business or everyday life.

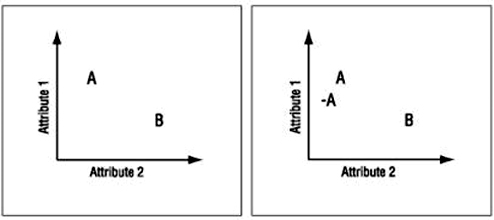

I have to say, I really like the picture below as it perfectly portrays the main idea of this article. Interestingly, squares A and B have the same color in this picture. (You can check it yourself using Photoshop or some other photo-editing tool if you don’t believe me.)

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

Pricing experiments – the bait principle

We rarely think in absolute terms, and we don’t have a universal measure to understand the value of a certain thing. Therefore, we tend to evaluate things by comparing them to others.

The book “Predictably Irrational” by Dan Ariely begins with a story about an experiment that we will discuss further on. You can also find the author’s story about this experiment in his TED talk.

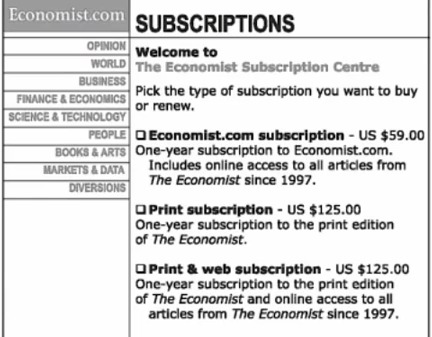

In the picture below you can see a magazine subscription page with three options:

- a web subscription ($59)

- a print subscription ($125)

- print + web subscription ($125)

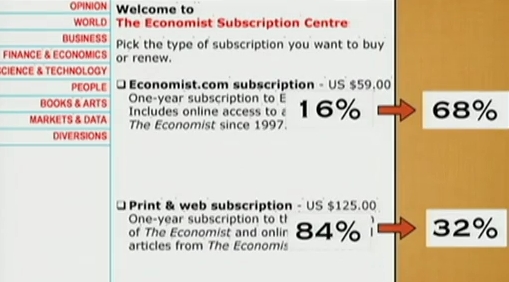

The first group of people in the experiment saw this version of the page. 84% of them chose the third option, and only 16% preferred the first one. None of them purchased the second option.

Then the second option was excluded, which left only two options:

- web subscription ($ 59)

a print subscription ($125)- print + web subscription ($ 125)

This time the preferences looked different: 68% of the people purchased the web subscription and 32% opted for the print+web.

It turns out that, despite first impressions, the second option wasn’t meaningless. In fact, it helped nudge buyers towards a more expensive tariff plan.

The same principle was illustrated by an experiment with a tour vacation package. At first, people saw two options: a tour to Rome (A) and a tour to Paris (B). That was a difficult choice to make and they couldn’t make up their minds for a long time.

Then, a different group of people were presented with a new offer. The tourists saw three options: a tour to Rome with free breakfasts (A), a tour to Paris with free breakfasts as well (B) and a tour to Rome without breakfasts(A-). This small modification changed the distribution of purchases dramatically, with Rome leading the race.

The picture below demonstrates the principle used in these experiments. People are not only inclined to compare options to each other, but also tend to so with those that are more similar.

How can we use it?

Add a special “bait” to your tariff line or product catalog, which will become “A-” for the tariff (plan) that you really want to sell.

The contrast principle

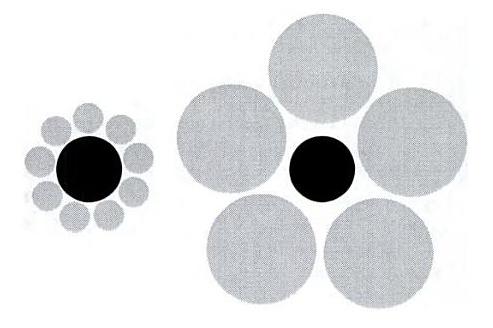

The circles drawn in the center of the image above are identical. But depending on their environment, their perceived size changes.

The idea of relativity and the limitations of human perception underlies almost all the experiments described in this article. People can’t isolate and analyze all the factors necessary for a “rational” decision-making, especially in new and unfamiliar situations where these factors are yet unknown. The lack of a ready-made pattern of behavior makes people rely on “simple” factors in decision-making (such as other people’s behavior, template principles, pre-designed baits, etc.), rather than the correct ones. People working in sales often use this principle to their advantage.

The bait principle, described earlier, is a special case of the contrast principle. The main idea is that people are not only inclined to compare things, but they will do it the context in which they currently are. And the given context can be altered.

We can spot the contrast principle being used all around us. Here are a few examples:

Salesmen in retail stores try to sell the most expensive things first, or at least offer them to customers. For instance, a person who came to buy a suit is first shown the suits. When the customer makes his choice, then the salesperson suggests appropriate accessories, such as a tie to go with the suit. Compared to the suit’s price, the tie looks very inexpensive and is an easy upsell.

The real estate agent shows her potential buyers a rather lousy overpriced apartment first. Then she takes the future home-owners to the apartment that she has in mind for them. Compared to the first option, the second home seems to be a perfect bargain and great luck.

You can usually spot a very expensive offer when choosing from tariff plans. This overpriced unit is not intended for sale. Its purpose is to make other options look more affordable.

A friend first asks you to lend him $2,000, and then goes down to $1,000 (which he originally wanted to get).

To evaluate the effect of the contrast principle try the following experiment: Bring three buckets of water – one hot, one warm, and the third one cold. First dip one hand in the hot water and the other in the bucket with cold water. Wait a while, and then take out both hands and dip them in the bucket with warm water at the same time. Can you tell the difference?

How can we use it?

You can modify the context of your customer when she is making a decision. You can also influence the order in which you demonstrate the goods, as it changes the customer’s susceptibility to prices too.

Does your insurance certificate number affect how much you are willing to pay?

Dan Ariely gives us another interesting experiment in his book. The purpose of this experiment is to verify the hypothesis that prices are determined on the basis of rational factors, e.g., the value of a particular product.

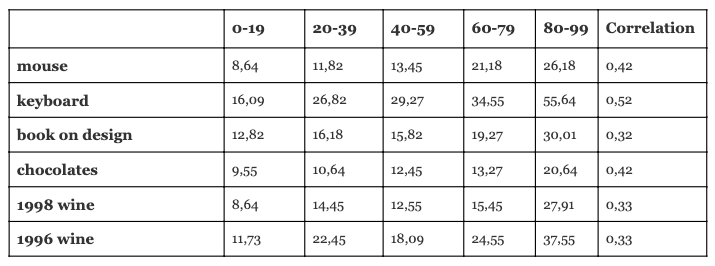

The test’s participants were asked to write down the last two digits of their insurance certificates, and then evaluate the cost of a number of goods.

Do you think the written figures affected the valuation? Yes, they did. There was a clear correlation between the last digits of the insurance certificate number and the cost estimates. It is fascinating that within each range of numbers, the ratio of goods prices is also present, which again suggests that people are guided by the available prices to assess the rest of the offered goods.

There were many experiments like that one. For example, court judges were asked to roll a die before passing sentence, and the length of their verdict correlated with the values they got on the dice rolled. Of course, the judges didn’t realize that the die roll had affected them.

In another experiment, participants were asked to remember the number hit on a roulette, and then estimate the number of dentists in their city. Again, their estimates correlated with the number they hit.

In yet another test, participants were asked to estimate the proportion of African states within the UN. The first group to record their answers was given a sheet with the number 65 on top of it, and the second group had number 10 on their sheet. The average result the first group wrote was 45%, while the second group’s average was 25%. The correct answer at the time of the experiment was 23%, but this is not important. The number that the participants saw on their sheets affected their decision.

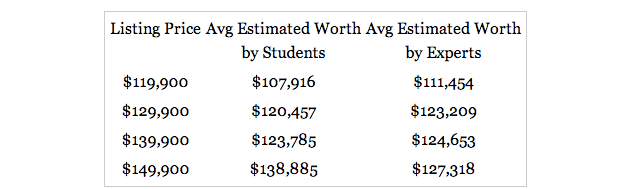

Here is another experiment showing that such “anchors” affect professionals of a certain field as well. The participants in this experiment were real estate agents and students.

All participants received the following material: The information about houses sold recently in a certain area, a list of houses that are on sale, and the price that each of their owners had set for them.

The participants were divided into four groups, and the materials they received differed only in the price set by the owner of the house. Based on the given information, the participants were asked to evaluate the real value of the house. Thus, they had objective data about the house prices in the area, as well as a subjective assessment of the value by its owner.

You can see the results in the table below.

Even though the experiment provided a lot of information about other houses and transactions in the area, the price set by the owner of the house affected the final assessment. Moreover, it affected not only the students, but the professional real estate agents as well.

How can we use it?

Do not lower prices. The price that you declare at the very beginning will become the reference point. You can also try to show your customers big numbers before starting to talk about the money.

The magic number 9

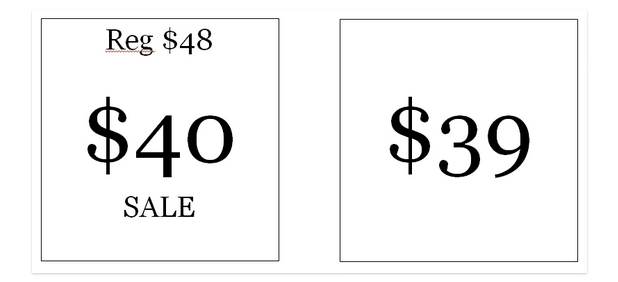

Employees at the University of Chicago and MIT conducted an interesting experiment.

They divided the subscribers of one clothing catalog into three equal groups and sent them different versions of the catalog. In the original catalog, some items cost $39, in other versions the same items cost $34 and $44.

As a result, the number of orders for these positions in the original group exceeded all the others, including the $34 option. It is difficult to find a logical explanation for this, but apparently the prices that end with 9 trigger some kind of automatic mechanism.

In order to study the effect of the digit 9 in pricing, there was another experiment, where they tried to compare the effectiveness of two price tags.

In this experiment, the left option showed better results.

But the winner of the first round had no chance when compared to the option presented below. The discounted price tag ending with a 9 won by a long shot.

How can we use it?

The digit 9 has become a mandatory component of any pricing. And despite the lack of any rational explanations, “9” works (and even if it doesn’t work in your case, you don’t lose anything).

The way information is presented to us influences our decision

One way to influence the human perception of a particular product is to change the way we talk about it.

For example, consider the following two events:

A: A drunken motorist runs over a woman.

B: A motorist runs over a woman.

Which of these events is more likely to happen? If you think that the probability of event A is greater, then you have joined the overwhelming majority—who happen to be wrong (if not, then good job!). Event A is a subset of an event B, so its probability is less than or equal to the probability of event B. The reason for this error is the presence of the adjective “drunk,” which gives the information more weight, concreteness and credibility.

Here is another example. The participants in the experiment were asked: “You are abroad and want to use some local airlines to visit a deserted island.” Then, in one case, tourists were told that if they fly with this airline once a year, there is a possibility of one air crash happening in a thousand years on average. The other group was told that on average, one in every thousand flights from this airline ends in a disaster. 100% of the tourists from the first group agreed to take the trip. In the second group, the percentage of positive responses dropped to 30%.

Mathematically equivalent statements are not necessarily equivalent psychologically.

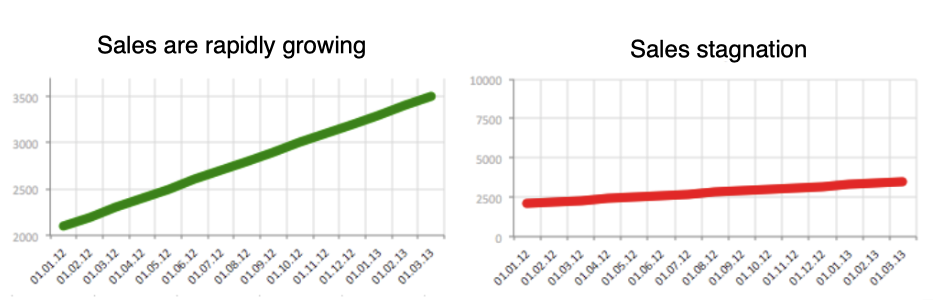

I also learned to apply this technique as an analyst. Below are two charts demonstrating revenue growth from two different companies. Which of them would make you feel better if you were the CEO?

In fact, both charts show the same data. What differs is the range of the vertical axis. The first chart is better suited for reports to investors. The second one is best for discussing annual bonuses for the sales team.

How can we use it?

The way you present the price and information of your product can easily affect the final decision of the buyer. Offering to proceed with a $1 per day tariff and the one that costs $350 per year are mathematically equivalent, but trigger different reactions in customers. The first option can be compared to purchasing a water bottle in a grocery store, and the second option is more like purchasing a mobile phone.

New categories and the dangers of small decisions

Every day, each of us makes many decisions. If we consider the pros and cons in each of the situations we face, our life will turn into a nightmare. Therefore, we tend to base our decisions on things we’ve experienced before, to make decisions easier. This approach works well in most situations, but sometimes it fails.

Do you remember your first Starbucks experience? You go to a nice place where they sell coffee for $3, while in most other coffee stores the price is much lower. But well, you are already there, so you decide to have a cup of coffee and enjoy the environment.

The next time you find yourself at Starbucks, instead of thinking about all the pros and cons (which is a good idea, as your daily coffee makes you spend about $1,000 per year), based on your previous experience (because you’d already bought coffee there and you liked it), you will make the same decision. This is how we form habits, and you probably know how difficult it is to get rid of them, including the bad ones.

This example is not an experiment with undeniable conclusions. But it illustrates the following idea well: People tend to be consistent (i.e., base their behavior on previous experience and decisions). People also tend to form new “rules” when they encounter something for the first time. Starbucks is very different from other coffee stores. Therefore, when interacting with them, people create new rules instead of resorting to existing patterns.

Here is another illustration of the idea mentioned above. When the sales agents of a health insurance company that was selling its services via phone asked people (who agreed to proceed) why they chose their company, the proportion of those who eventually decided to purchase the insurance increased significantly. As they thought about the answer to this question, the respondents subconsciously convinced themselves that they had made the right choice, further strengthening their decision and eventually leading to their making the purchase.

By agreeing to insignificant requirements, answering specially crafted questions, and making small decisions, we can often change our minds (and those of others) about certain things.

How can we use it?

If you want to change the rules of the game in a field that you are about to enter, try to portray your product as something new and different. Doing so will enable you to set the rules of the game from scratch and be the first one to establish the anchor. And when you install the anchor, do not lower the price; there will still be time for that (making a discount always sounds better than raising the price).

The influence of the situation and expectations on the price

Imagine a subway station where some unfamiliar musician is playing the violin. Now assume we replace the unknown musician with one of the most famous violinists of our time there. Will he make more money than the first musician?

Joshua Bell, one of the best concert violinists in the world played for free, for 45 minutes, on a violin worth $3.5 million dollars at a subway station. He managed to raise $32. Most people (98%) who passed by paid no attention to him, only 2% gave him some money, and less than 0.5% stopped to listen (those were the people who actually recognized him).

The numerical metrics didn’t look any better than those of ordinary musicians playing at the station. The bustling atmosphere of the subway leveled the outstanding musician with his mediocre peers, even though his talent had not changed. In many areas, people can’t objectively evaluate the skill and quality of their experience. Therefore, the relevant environment, in fact, the “flow” they are currently in, plays an important role in shaping their perceptions. What do you think would happen if an ordinary musician was invited to play at Carnegie Hall? Would the listeners notice the difference, or would their preformed expectations from visiting the famous concert venue raise the young musician the title of a new rising star?

Here is another interesting experiment that was conducted at MIT. A small tent was set up near the campus, where students were offered free coffee. After getting their coffee, the participants could have added some unusual ingredients to it such as cloves, nutmeg, orange zest, anise, sweet pepper or cardamom. Then they were asked to fill a questionnaire (how much they liked the coffee, how much would they be willing to pay for it, whether they would recommend it to their friends, and would they revisit such an unusual coffee spot).

The experiment lasted for a few days, but sometimes the researchers changed the conditions a little. The only thing they changed was the way the extra ingredients were served. In some cases, they served them on plastic plates with plastic spoons, while in others they placed the ingredients on beautiful metal plates with silver spoons.

The way the extra ingredients were presented didn’t change the fact that students wouldn’t take them (who would drink coffee with orange zest, after all?), but those who received coffee when the table was beautifully set appreciated the taste way more, and were also ready to pay more for it.

Here are some more experiments. In one case, the researchers added a little red food coloring to white wine. Afterwards, they asked a group of wine experts to evaluate the sweetness of the ordinary wine compared to the colored one (the two were identical, obviously). In 90% of cases, the tinted wine was considered sweeter.

In another experiment, researchers asked Coca-Cola enthusiasts to tell them whether they prefer Coca-Cola or Pepsi. After that, the participants were offered to try both drinks and to confirm or refute their previous statements. 70% of them didn’t change their minds, although the researchers had switched the content of the Pepsi and Coca Cola cans.

In one case, the participants were given brochures describing the capabilities of a new audio system. The only difference between the brochures was that the first one was published on behalf of the system’s manufacturer and the second one on behalf of an independent research center. The participants who had seen the second brochure were willing to pay twice as much as the first group for the audio system.

How can we use it?

When we make decisions, our perception is influenced by a lot of factors such as presentation, packaging, brand, opinions of people around us, experts’ opinions, our own expectations, etc. Each of these factors can ultimately determine how much a person will like your product and how much she will be willing to pay for it.

Free vs Paid

Years ago, Amazon started offering free shipping for orders over a certain amount. The idea was simple: You could order one book for $20 and pay another $5 for delivery, or buy an additional book for another $15 and get free shipping.

As a result, Amazon sales grew significantly in all regions except France, where the situation remained the same. You might think that the French were more rational or perhaps the free delivery didn’t motivate them enough. Well, not really. The reason was that Amazon employees in France slightly changed the terms of the offer: they reduced the cost of delivery to 1 franc (about $0.2) with the order amount above the required minimum. Once the delivery was made free, there was a rise in sales as well.

Another example is the Museum Night, when museum entrance are free of charge. Even people who are not interested in museums line up to get in for free. (Although I can hardly believe that the real culture-lust is not worth a few dollars.)

Another illustration of the enormous appeal of “free” stuff for people is the victorious march of f2p in the mobile market. Paid apps don’t cost much – just a few dollars, but they can’t compete with the free apps. Here is a simple example from my experience: during the time “Cut the Rope,” a game I worked on, was featured in the App Store’s Free App of the Week section, downloads instantly grew by tens of thousands of times. There are a few reasons for that. Perhaps the $1 price held these users back, or maybe making it free made the app so attractive.

But in this particular case, there was something else I was looking for. I decided to compare how those who got it for free and those paid for it went through the levels in the game. There was a hypothesis that those who got it for “free” should stop using the game faster and sooner than those who paid for it.

The hypothesis turned out to be wrong. The users of both the free and the paid version had identical behavior in the first 40 levels However, after level 40, the “free” players started quitting the game much faster. I interpreted this as those who received the game for free appreciated it less, so their motivation to go till the end or return to it after a couple of days was less. I will tell you more about the effect of the product price on our perception in the next section.

How can we use it?

The word “free” makes any product more attractive to its potential customers. If you have a way to distribute your product for free, at least partially (a trial option, a limited version), then make sure to use it. This approach will greatly expand the top of your funnel. Once done, you will simply have to learn how to convert these new users into the paying ones.

Does the price of a product affect its perceived value?

The following experiment was conducted in Boston at MIT when checking the effectiveness of a new painkiller. Participants were taken to the reception room, where they could view the results of tests on other painkillers. Then they were connected to a machine that generates electrical charge and did the first round. After each round, the participants had to use a computer to evaluate the pain on a special scale. Next, the subjects were given a pain medication, and a similar series of electrical shocks was performed again, measuring their pain perception after taking the pill.

But in reality there was no pain medication. The pill given to the participants was a simple vitamin C supplement. The test groups were also given different brochures. The first one said that the medication would be retailed at $3 per pill, while the second one priced each pill at 10 cents.

The results looked astonishing. With a vitamin C priced at $3, 100% of participants experienced relief. But the drug priced at $0.1 only worked in 50% of cases. The described effect is called the Placebo effect (the effect when the relief is not associated with the properties of the drug substance, but with the patient’s faith in them). As the experiment showed, the effect in this case correlated with the cost of the “pain medication.” Thus, the price itself can affect our experience in interacting with the product.

I observed a similar effect in my own business when I was producing and selling metal license plates (sold via partner brick-and-mortar stores and through our own online store). At the start, the prices we set were relatively low ($3-5). But in a few months, we raised the prices by 2-3 times, and the plates then cost $15-25. Contrary to our expectations, the conversion rate almost doubled, as well as the average order amount.

I have no idea about the exact reasons behind this, but I suppose that the following factors could have influenced the results:

- Metal license plates are a unique product, so people didn’t have the context to verify the adequacy of the price. In fact, their first contact with the product on the website established an “anchor” for products in this category.

- People bought plates as gifts. Raising the price to $25, we fell into the generally accepted price range of a gift (after all, people rarely spend as little as $3-5 on a present).

How can we use it?

Clearly prices is one of the barriers standing between a customer and a desired product. But in some cases, price can have a considerable effect on how customers view products, how they value it, and how much they like it. Therefore, when setting the price for your product, think about whether it will “help” people better if it costs more. Then you will have a win-win solution.

In the next section, I will talk about a few pricing experiments that we did when I worked at ZeptoLab, a global gaming company. ZeptoLab launched back in 2010 with the game Cut the Rope, featuring the cheerful green Om Nom character, whose biggest passion are candies. Since then, Cut the Rope games have been downloaded more than 1.2 billion times.

Pricing experiments at Zeptolab

Change 500 Superpowers to Unlimited

At one point, we made one small change to Cut the Rope. The objective of the game is to feed candy to a little green creature named Om Nom while collecting stars.

We were selling superpower packs in the game (special things that help to pass game levels). There were four packs respectively containing 25, 50, 150 and 500 superpowers.

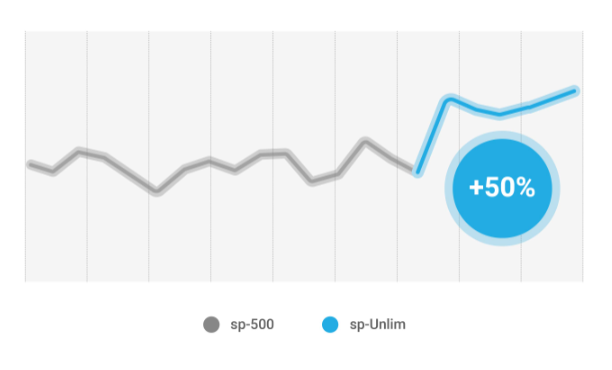

We increased the biggest power pack from 500 to infinity. Practically, nothing changed. 500 superpowers were more than enough for the entire game, and very few users had spent all of it. However, after the change was made, the revenue from this pack grew by 50% while the revenue from other packs didn’t change. We assumed people like the lack of restrictions, or maybe the infinity icon looked nice.

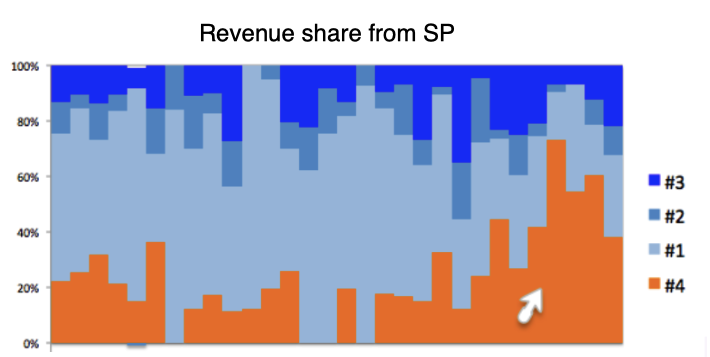

On the pic: Revenue from the 4th super power pack

Adding a paid shortcut to content that is difficult to obtain for free

This was another interesting case reflecting the influence of the presentation method on our perception.

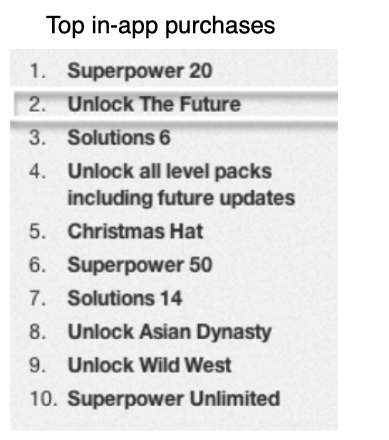

Each update to Cut the Rope adds new content to the game (a box with new levels). At some point, we added the Future box to Cut the Rope Time Travel. But to open it, players had to go through all the previous levels and get the maximum number of stars. Thus, we gave users the opportunity to get a box for free.

As a result, most users used an alternative: they simply bought the box. And a few users replayed the old levels to get the maximum number of stars (some of them bought power packs).

Interestingly, there was not a single negative review in the app store. On the contrary, everyone was extremely positive about the change. The future box became the second most popular in-app purchase in the game.

The opposite happened when we were launching Cut The Rope 2 on iOS. In Cut the Rope 2, each box had locked levels that could be opened by collecting clover on other levels of the box. To collect the clover, the players needed power boxes, which were sold or distributed as daily gifts.

The purpose of adding these locked levels wasn’t to make money. The hypothesis was that it will help to improve retention rate: people would come back, get power boxes through daily gifts, and replay old levels to unlock the additional ones.

Unfortunately, users viewed it as a scheme to get them to pay, and shared their thoughts in their reviews. I think it’s clear that in reality it didn’t bring us any money. A few days later we released an update where we simplified the described mechanics (a lot of users were grateful and changed their negative reviews and ratings after all).

What is the takeaway from all these stories? Users don’t appreciate it when you try to trick them out of their money, or when they think you are doing that. A better approach would be to give them the opportunity to get what they want for free (even with a lot of work involved), and give an alternative purchase option. In this case the purchase will be perceived as a small cheat to make life easier instead of a shady scheme to get users to pay.

From cheap to expensive and vice versa

I read many articles that recommend a special placement of tariff plans for a product. Then I decided to conduct an experiment in one of our games.

At some point, we replaced the order of displaying the superpower packs (SP) from ascending to descending.

Did anything change? Yes, it did. As a result, the revenues from different packs of superpowers were redistributed, but the ARPU remained unchanged.

On the graph below, the arrow indicates the week when the replacement was made. We can see that the revenue share from the 4-pack sales (the most expensive one) has grown significantly from that moment.

What does it mean? Placement affects sales. But in our app, despite the redistribution of revenue from pack sales, the change didn’t affect the overall monetization metrics. It may, however, affect yours.

Summing up

The perception of value is subjective and may be distorted and influenced. Therefore, many factors can influence the price a particular person is willing to pay for a product. Among such factors are competition, habits, environment, way of presentation, the behavior of people around, and so much more.

In this article, I collected a number of experiments demonstrating the irrational and unconscious behavior of people, especially when it comes to buying things. You can apply many of these experiments to your business (make sure to tell me about the results later).

Pricing is an important and integral part of creating products. But if you keep in mind that price is a reflection of the benefit (value) that you bring to your customers, then everything becomes easier. A key aspect of your business is maximizing the value of your product, rather than optimizing its pricing. That is why the potential effect of optimizing the pricing is usually less significant than any major changes you make at the product level.

I must admit, however, that playing with prices and the way they are presented is always a lot of fun. There experiments are easy to conduct and their verified success metrics allow you to get positive results rather quickly.

Sources:

When working on this article, I used many different sources. You can find the list below:

- «Pricing experiments you might not know, but can learn from», Peep Laja

- «Predictably irrational», Dan Ariely

- Robert Cialdini Principles of Persuasion

- The Black Swan by Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- «The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives», Leonard Mlodinow

If you liked the essay, then in addition to the list above, I recommend you to take a look at the books Freakonomics, SuperFreakonomics, and The Tipping Point.

P.S. If you have conducted interesting experiments with you product’s pricing, make sure to share in the comments below!

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.