In the previous essay of this series, we discussed how established companies and products can grow by entering new markets through movement into adjacent dependent segments in the value chain. Today, we will talk about another growth path: building new products for an established user base.

We will explore several examples where companies have successfully—and at times, not so successfully—used this growth path. We will also try to define a set of questions that will help to make a more informed decision about choosing this vector for a particular company.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

Examples of growth through the creation of new products for the current audience

There’s a very simple logic behind creating new products for an established user base. The company has already acquired and built relationships with a specific audience, and it understands and knows this audience well. Consequently the company is more likely to succeed in creating a new product for this audience. There is extra value in this move as it may help the company to strengthen its relationship with current customers.

You can find examples of using this growth tactic everywhere.

From 1995 to 1999, Amazon was selling books online, gradually growing its audience and building logistics and a network of warehouses. Then the company began to sequentially launch new goods categories (e.g., audio and video discs, toys, household items, etc.). New categories covered more and more needs of the service’s current audience, and also created opportunities for further expansion.

Apple is regularly releasing new devices (new phones, watches, headphones) targeting the loyal audience of their brand. Chinese tech giant Xiaomi is moving in a similar direction. In 2013, the company presented a strategy called “Mi Ecosystem Companies.” Xiaomi decided to invest in 100 companies over five years to create its own devices in all major hardware categories. By 2016, there were 55 companies within this ecosystem. Of these companies, 29 were incubated from the ground up by Xiaomi. Four of them were already worth over $1B in 2016.

Angry Birds is one of the first popular games on smartphones. The loyal base of its fans has become the foundation for dozens of new games, animated series, two movies and many other products and businesses built around its beloved characters.

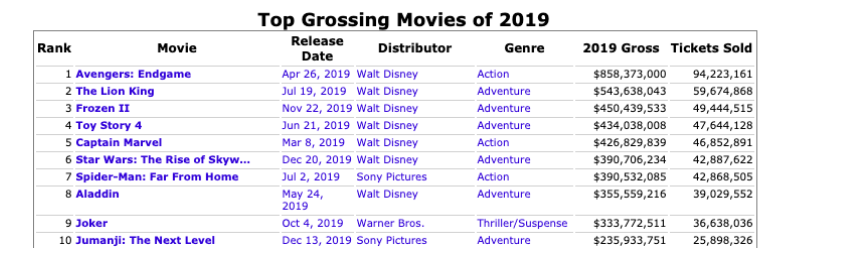

Disney has acquired a number of popular franchises (such as Marvel and Star Wars) and now regularly releases new films for fans of each of the cinematic universes. Other film studios are moving in a similar direction, mainly launching sequels to successful films or movies in popular cinematic universes. This approach proved to be less risky and more profitable than launching a completely new product in the market. Look at the list of the Top Grossing Movies of 2019. You are unlikely to find anything fundamentally new there.

Many tech giants have grown by launching new products to their loyal audience through their distribution channels

Many modern tech giants used the growth strategy of launching new products to their loyal audience through their developed distribution channels.

Here’s how Marc Andreessen describes this process in an interview with Elad Gil, the author of High Growth Handbook:

«In fact, the general model for successful tech companies, contrary to myth and legend, is that they become distribution-centric rather than product-centric. They become a distribution channel, so they can get to the world. And then they put many new products through that distribution channel. One of the things that’s most frustrating for a startup is that it will sometimes have a better product but get beaten by a company that has a better distribution channel. In the history of the tech industry, that’s actually been a more common pattern. That has led to the rise of these giant companies over the last fifty, sixty, seventy years, like IBM, Microsoft, Cisco, and many others.»

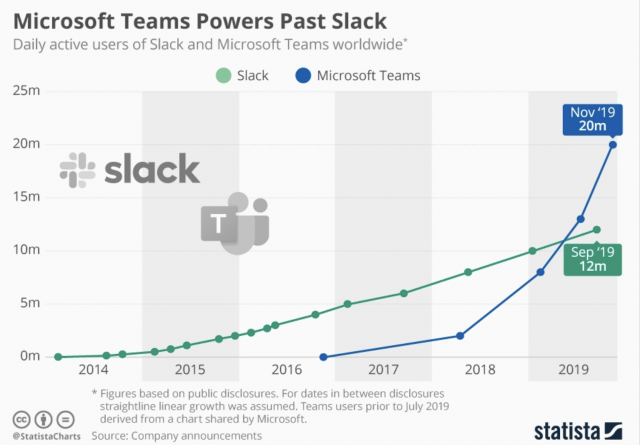

A vivid example is Microsoft Teams, which crushed Slack by using the above model to introduce new products to the market. Microsoft made a doppelganger of the successful product, and then used its distribution channels to deliver the product to the market at a much faster pace than Slack. Read more details about the dynamics of the work messenger market here.

Startup acquisitions provide opportunities to quickly deliver product value to an established user base

Launching new products for existing audiences through built-in distribution channels is such an effective growth model that it has become one of the main reasons large companies find it profitable to acquire startups.

Instead of designing new products within corporations by employing highly paid engineers and managers, it is usually more profitable to buy a ready-made product that has proven its value. The logic is for big companies to let thousands of small teams with low wages and surviving on their own or their investors’ money test a large number of risky product hypotheses. As soon as one of them creates something valuable, the big company will intervene and acquire the successful team and its product and quickly deliver this new value to its large audience.

Ultimately, it turns out to be much less costly than checking thousands of product hypotheses inside the company. It is more profitable for corporations to spend their resources on developing current products or moving in new directions where they have an “unfair” advantage.

Here’s what Ben Thompson says about it:

“The first group that benefits from large tech company acquisitions is end users. The fastest possible way for a new technology or feature to be diffused to users broadly is for it to be incorporated by one of the large platforms or Aggregators. Suddenly, instead of reaching a few thousand or even a few million people, a new technology can reach billions of people. It’s difficult to overstate how compelling this point is from a consumer welfare perspective: banning acquisitions means denying billions of people access to a particular technology for years, if not forever.”

New products for the current audience != Launching new products in dependent related niches in the value chain

I consider it important to separate the following two growth paths: launching products in dependent segments of the company’s value chain, and launching new products for the current audience of the company.

Launching a new category of goods on Amazon and launching the marketplace on Amazon Prime are examples of creating new products for the current audience of the company.

An example of moving along the value chain into dependent segments is Amazon’s launch of products under its own brand in categories dominated by third-party merchants on Amazon, or creating their own logistics infrastructure.

In the first case, the degree of uncertainty is much higher, since the company doesn’t have any preliminary evidence of the demand for the new product. In the second case, the company knows in advance that a particular product is in demand, and has the leverage to control its use (logistics companies get delivery orders from Amazon).

Ways to assess the effectiveness of growth through launching new products for your audience

Despite a large number of successful examples of using the launch of new products for a loyal user base as a growth strategy, this method doesn’t always work. Below we will examine a number of questions whose answers will help you make more structured decisions about the appropriateness of choosing such a growth path.

The added value of a new product

One of the important questions that usually escapes attention when launching new products within an existing business is: What added value will your product bring to your existing audience?

If the only reason for success that you can think of is the access to the current audience of the company, then it would be wise to stop and re-evaluate the feasibility of the project.

If your customers are already using similar products made by competitors, or they can be using them but aren’t because they don’t need them, then providing them with a similar service doesn’t make sense.

The ability to use the existing distribution channels and access to the customer base should be considered as an additional push for a new product. But if there is nothing to “push” (say the product doesn’t create any added value for the target user segment), then there won’t be much benefit in having access to the product’s current audience.

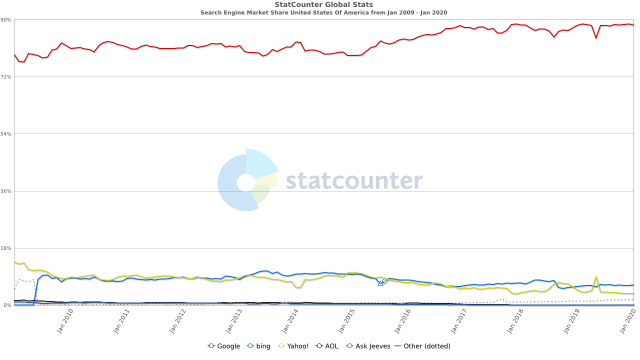

Users of Microsoft Windows had a clear need for a search engine, but Bing and its predecessors from Microsoft had zero (or even negative) added value compared to Google, which already enjoyed huge penetration among Internet users. Therefore, despite Microsoft’s distribution power and its huge user base, its search product was never destined to win a significant share of the search engine market.

Facebook made numerous Snapchat clone apps, but none of them yielded significant results. For a younger audience, these products didn’t create any added value in comparison to Snapchat (which is protected by network effects), and for the majority of Facebook users, such a product wasn’t interesting at all (just like Snapchat itself).

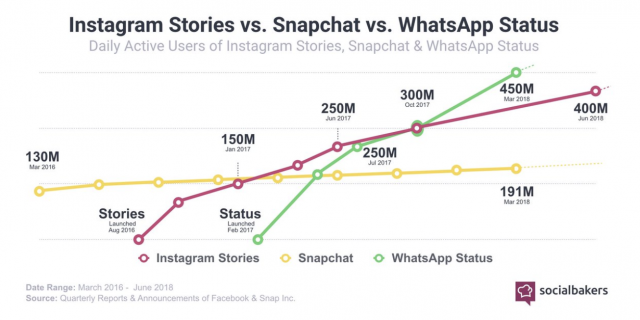

After drawing conclusions out of this situation, Facebook changed their strategy and launched Stories in Instagram, Whatsapp, Messenger and Facebook. It turned out that this product clearly had an added value. First, Snapchat hadn’t yet reached a substantial share of Instagram/Facebook/Whatsapp users. Second, the quality bar for content shared in Stories was much lower than in the feed, which led to an increase in the volume of content being created and to new use cases for Facebook products.

You can see the results on the following graph, which demonstrates Stories’ audience growth rate across products. Pay close attention to the growth curve of Stories in Whatsapp, which introduced a new communication format in markets where it hadn’t existed before—that is, created the maximum added value in those segments.

Defense mechanisms of future competitors

This question follows the previous one, but it is worth asking it separately. Different products have different defensibility levels. In some markets, such as mobile games, it is easier to win market share. In others, it might be almost impossible (the US ecommerce market dominated by Amazon, or the social media market dominated by Facebook).

The prospects of a new product largely depends on the defense mechanisms of rival products. The more effective the defenses of the product you are planning to take users from, the greater the added value of your product must be to compel those users to make the switch. It is important to keep in mind that different defense mechanisms exist at different levels. For example, it can be long-term multi-year contracts, network effects, or the cost of retraining employees and teaching them how to use new software.

To get an impression, let’s go back to the Microsoft Teams-Slack standoff. Microsoft Teams looks a lot like a Slack doppelganger, so for those who are using Slack, the product has little added value (apart from the fact that Office 365 customers get it for free). Moreover, the Slack user base is very well protected by its network effects, as well as organizations’ inertia in changing B2B solutions.

When you bring a new product to the market, it is important to see what is the product you are replacing. Granted, Teams’ added value for those who are already using Slack is minimal. However, when you look at users who are using email, Skype for Business or other outdated tools for work communication, Teams provides significant added value. And among Microsoft Office 365 users, which has more than 100M paying users, the share of the audience that can experience this added value exceeds 90%. That’s where the growth comes from.

Adapting a new product to the current value chain

In the article “The Value Chain Constraint”, Ben Thompson demonstrates that even large tech giants with unlimited resources often encounter failures when launching new products in value chains that are fundamentally different from the company’s core business. Creating and launching such a product on the market requires other skills, a different infrastructure, and a different organizational structure and company culture.

Say you are running a large and profitable bus company. You have studied your company’s audience and found out that many of them need banking services. This doesn’t mean that if your bus company establishes a bank, then its chances of success will be greater just because you have access to a loyal audience of passengers. These two products live in completely different value chains, which means founding a bank will be similar to launching a fundamentally new product for a new audience.

An interesting real-world example is Amazon’s problems in entering the groceries market. In 2018, Amazon Fresh saw a year-over-year decrease in the number of customers. Mind that this is the segment where Walmart, an Amazon competitor, is enjoying maximum growth rate.

This is because Amazon’s value chain is fundamentally different from that of groceries. In fact, Amazon will have to build everything from scratch to sell groceries, and in this regard, they lagged far behind Walmart, which is in a better position to bring such a product to the market (in this light, buying Whole Foods carries a totally new meaning). Due to the mismatch in value chains, the direct access to the huge customer base who regularly shop at Amazon doesn’t create any significant advantage in the new market. Although it would seem that in both cases, there are very similar user audiences who are making purchases.

Here is what Ben Thompson has to say about the situation:

«That, though, is precisely why groceries is worth examining: as I explained when Amazon bought Whole Foods, perishable goods are not well-suited to Amazon’s value chain. Superior selection has diminishing returns, quality varies on an item-by-item basis within a single SKU, and, most importantly, the quality of items degrades with time and transport. In other words, they are a great fit for stores, not distribution centers.

In this view, Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods was an attempt to acquire a first best customer for its grocery delivery operation, one that would efficiently store and sell perishable goods that weren’t suitable for Amazon’s traditional e-commerce model. And, to be clear, this strategy may yet succeed, but only to the extent Amazon builds a completely new set of capabilities and integrations that will probably end up looking a lot like Walmart, which has a massive head start it is clearly taking advantage of.

In other words, what matters is not “technological innovation”; what matters is value chains and the point of integration on which a company’s sustainable differentiation is built; stray too far and even the most fearsome companies become also-rans.”

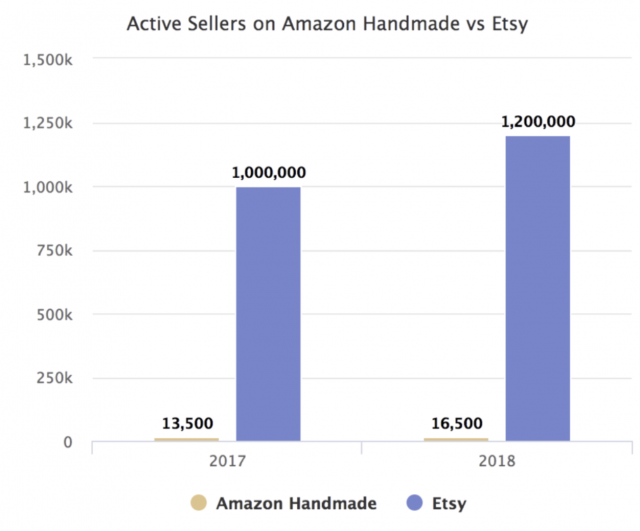

Another example of the importance of matching value chains is Amazon’s failure with its service Handmade, which was supposed to be the killer of Etsy. The key component in the value chain for the marketplace of handmade products is the unique supply, that is, the craftsmen who create handmade products. For many years, the Etsy team worked on onboarding craftsmen, visiting various exhibitions and local fairs, as well as creating many other mechanisms for attracting these producers. Without this important component, the huge purchasing power of Amazon customers, its distribution centers,and next-day delivery didn’t provide any significant advantage in the handmade goods market (moreover, many of these characteristics are of little importance to handmade-craft lovers).

The consequences of not adapting value chains with product growth manifests themselves not only in the fact that the product fails to receive any additional help from the parent company, but also in the fact that the company’s expertise and best practices in its current value chain may not work well in the new value chains.

I faced this situation when I was working on Workplace by Facebook. The team developing Workplace was based in London, which gave it a significant level of independence. However, many people in the team (especially those with prior experience in other Facebook teams) didn’t realize that an Enterprise B2B product doesn’t play by the rules of a B2C social product. This resulted in the team trying to develop and grow the product according to the principles and approaches that had worked for the main Facebook products. I have to say, this didn’t always lead to good results.

Feel free to read more about value chains in this essay.

The complexity of the organizational structure of the company after the launch of a new product

Another point you should consider before launching a new product for the current audience is whether the organizational structure of the company is suitable for effectively integrating all the processes necessary for growing several products at once.

When two products exist in separate value chains but share resources, teams or processes at the same time, then the two products begin competing for vital resources, requesting people and their attention, triggering all sorts of conflicts at the product level, in plans, priorities, and/or resources. This also leads to new departments being formed in the team (often, the organizational structure of companies directly reflects how they’re integrated in the value chain), whose members end up being suspended between the two products.

If a new product requires a new team with different skills (and this team will exist separately from the main one), then the process should be treated as launching a new product for a new audience. We will talk about this growth path separately in one of the future essays.

The potential of a new product compared to the main business

Can you imagine a company launching a successfully growing business worth a billion dollars, but then closing it down?

For most companies, this will be a strange decision, but quite normal for companies like Google, Facebook or Apple. Compared to the company’s total value, the share of such a product is insignificant, but it distracts the company’s attention and resources. And if there are a lot of such projects, then it makes it really difficult to manage this system.

Before starting the development of new products within the company, it is important to take time to assess the potential behind it. I don’t think that after several years of investing in a new product, you will be glad to find out that it will only increase your current business’ revenue by 10-15% at best.

Summing it up

When launching a new product inside an already established company, you want to make the most out of assets you created while developing your first product. One way to do this is to build new products for your existing audience.

This is a very effective, universally used growth path. But to increase your chances of success, you should ask yourself these questions: What added value does a new product create for the target audience? Is this added value enough to make users switch from competitors’ products? Does this new product exist in the same value chain? What is the potential of this new business? Is it big enough?

However, even if you are satisfied with the answers, do not forget that the world around you is much more complex than it seems at first glance. Sometimes there is a small unseen detail that can break a system that would work perfectly otherwise.

Therefore, even if a new product creates enough added value for your audience and is able to break through the defenses of competitors, fits into the value chain, and doesn’t break the company’s management system, then your next step should be to find the cheapest way to test the key hypotheses behind the new product. In most cases, a significant part of the risks related to launching a new product can be removed by using experiments and qualitative user research before heavily investing into the development of the product itself.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.