I have been familiar with the concept of the value chains for quite a long time. However, it wasn’t until I read Ben Thompson’s Stratechery blog (I highly recommend reading it at https://stratechery.com/) that I came across its practical applications in market analysis. Looking at products and companies from the point of view of their position in the value chain opens up a new perspective that helps to understand them, find not-so-obvious opportunities, and make more effective decisions.

Today I’ll talk about value chains within the context of expanding an established business or product to new markets. There will be more essays devoted to companies entering the new markets. In each, I will focus on different aspects of this process.

In this series of essays, I want to analyze the possible ways for businesses and products to enter adjacent and new markets. I will also discuss the advantages, nuances and pitfalls of these methods.

In this post, I focus on one of the most risk-free ways to enter a new market, which basically involves moving along the value chain towards the related dependent segments.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

What is a value chain?

I will use the concept of a value chain in a much broader sense than the one introduced by Michael Porter in 1985.

We will consider the value chain as the structure of interactions between different market players who create the necessary value to meet the market’s demand.

A similar use of this concept can be found on the Stratechery blog. In the early years of the blog, the author looked at the value chain as a way of tracking the flow of money in an industry. But eventually, he came to a broader definition that describes the value chain as how different companies interact to create the value needed to meet the demand of a particular market.

Companies build different integrations within the value chain. This integration defines the defensibility of their market positions, the level of profitability, and the ability to expand to related niches. If it sounds abstract and vague, don’t worry. We have some examples coming up.

Value Chain Examples

Depending on the problem you are trying to solve, value chains can be visualized with varying degrees of detail. For example, here is how Ben Thompson describes in one of his essays the differences between the way Amazon and Walmart integrated into value chain aimed at satisfying the retail demand.

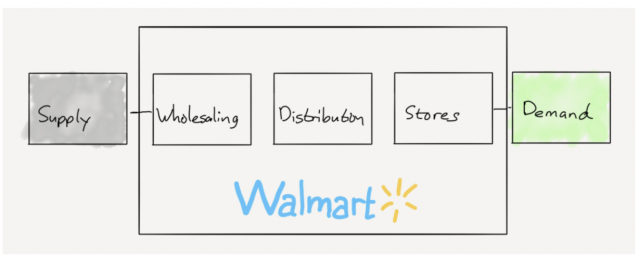

Walmart’s core business integrates the wholesale purchasing, distribution, and stores:

- First, Walmart is able to get the best price for their wholesale purchasing.

- Then, with the help of distribution centers and logistics infrastructure and special processes that ensure the freshness of perishable foods, it ensures the distribution of goods to the networks of their stores.

- Final demand is met through physical Walmart stores.

The Walmart value chain (Image credit: Stratechery blog)

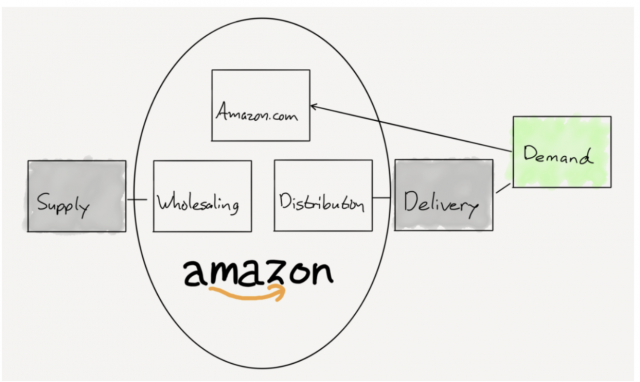

Amazon has created an alternative way to meet its retail demand:

- Amazon purchases goods from suppliers at wholesale prices.

- Amazon is also a marketplace and significant part of its inventory comes from third-party merchants (this is not included in Ben Thompson’s scheme, but I believe such a connection between supply and Amazon.com should be mentioned here, since the share of third-party sellers in Amazon’s GMV (Gross merchandise value) amounted to 58% in 2018).

- The final demand is met through Amazon’s online store, where customers order the necessary goods to be delivered.

- Quick and reliable delivery in this case requires the coordinated work of distribution centers, duplication of stock, quick fulfillment, as well as the participation of third-party logistics companies.

The Amazon value chain (Image credit: Stratechery blog).

The fundamental differences between how Amazon and Walmart are integrated into the value chain are as follows: Both companies were originally created to solve completely different tasks in retail and then organically developed on the basis of this foundation (such as purchasing food vs buying books, and then audio CDs and others categories of non-perishable goods) later on.

Now, the respective positions of Amazon and Walmart in the value chain largely determines which new markets each company can and cannot enter in a quick and efficient way.

Moving along the value chain into dependent segments is a predictable way to expand your business to new markets

What does the value chain have to do with expanding your business to new markets?

In fact, it has a lot to do with it. Analyzing a company’s position in the value chain may help find opportunities to enter a new market segment in many ways. I will discuss some of them in future essays. This essay, however, focuses on moving to adjacent value chain–dependent market segments.

Moving into adjacent market segments in the value chain is one of the predictable ways to expand the business to the new markets. Moreover, the company’s management tends to intuitively select such a development vector, gradually increasing the control of the system (building a vertically integrated system).

Amazon is a classic example of a company that is expanding to adjacent dependent segments of the value chain very aggressively.

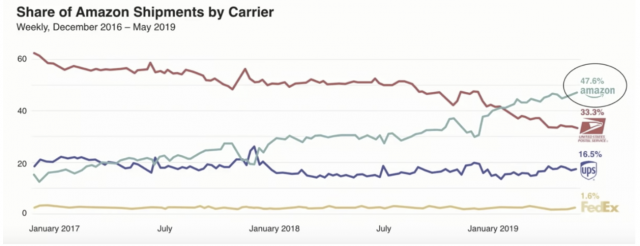

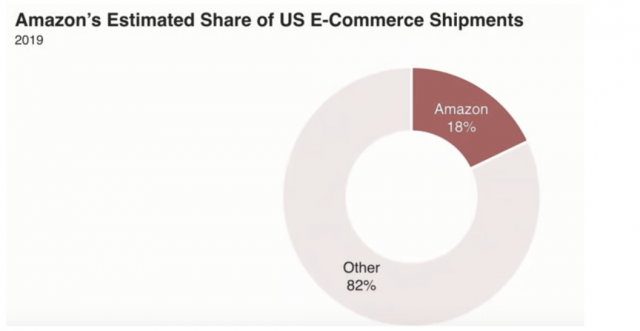

A few years ago, Amazon began to build its own delivery wing. Amazon now has over 20,000 trucks and 60 cargo planes under its wing. Over the past year, Amazon’s delivery has become its largest shipping channel, accounting for almost 50% of all of the deliveries Amazon has made.

While it is primarily serving its own delivery needs, Amazon already holds an 18% share of the US online delivery market. The next logical step would be to provide delivery services to other companies, probably at a lower price than the market, since Amazon doesn’t need to make this new business unit profitable in the short term. This is bad news for UPS and FedEx, which have been enjoying large profit and growth from Amazon’s booming ecommerce business (both companies’ revenues have almost tripled since 2000, and both of these companies are profitable).

Another example of a similar strategy is the manufacturing and selling of goods made under the Amazon brand. Amazon has done this in a number of categories that were previously dominated by third-party merchants. Amazon sees an interesting and profitable business segment that it can easily seize by taking advantage of its current position in the market.

Search engines are part of many value chains

The study of search engines provides many examples of how products and businesses launched through entering adjacent segments within the value chain. Due to the centrality of product search on the Internet, search engines have become a key component of many value chains. This has placed search engine companies at an advantageous gatekeeper position in many markets and helped them to maintain growth rates even after internet penetration slowed down on all the major markets.

For example, a large proportion of search queries are geo-related or related to organizations. Given this information, the logical step for Google, Baidu and Yandex was to create a predictable high quality experience for their end users by building their own mapping and location services. These services became a logical continuation of the search product at an early stage, but eventually got stronger and set off a race to conquer new adjacent segments of the value chain (such as traffic jams, routing, navigation, taxis).

Other similar examples might be Google Chrome, Google Translate and other services launched by the biggest search engine companies.

Moreover, these companies do not always have to build a product that will become a direct competitor to profit from an adjacent segment in the value chain. The most demonstrative example is the launch of advertising products on search engines, which caused a large-scale redistribution of profit within several value chains by creating competition between the players in their markets. This is how Google and Yandex created a mechanism that attracted a significant part of the companies that depend on search traffic and context advertising to their platforms.

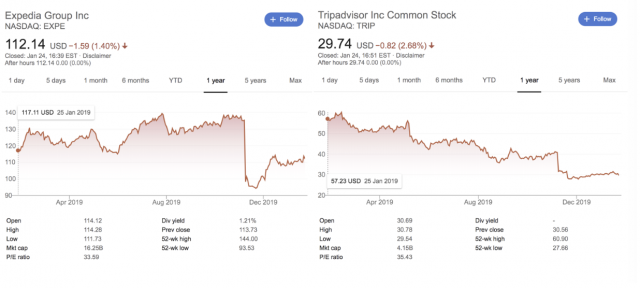

It is illustrative how Google now keeps squeezing large markets that are dependent on the company but have somehow managed to protect their profitability. Below you can find the stock price dynamics of Expedia and Tripadvisor for the past year. Both companies did not achieve their financial goals in the third quarter of 2019. As a result, the valuation of both companies fell by about 25% in one day. What did the companies have to say about this? Both said the reason for missing the targets was due to reduced visibility on organic search results.

For both companies, SEO is one of the key distribution channels. But with the user transition towards mobile devices, the increase in the number of ads in search results, and the presence of Featured Snippets, and the addition of special modules (for example, when you need to look through hotels using filters and say a map), the share of organic search traffic in the tourism segment began to plummet. This was a direct signal from Google that in order to get traffic from this search segment one will need to pay for ad placement (many of the features mentioned above provide paid prioritization).

A direct attack against a dominant player in the value chain will most likely fail

Not every company’s move into an adjacent segment in the value chain will lead to positive results. If the company plans to attack a player that occupies a stronger or even equal position, then chances of success are low.

Take VSCO, one of the pioneers of photo editing for smartphones and one of the most successful companies of its kind with a multi-million audience (the app has over 200M downloads). Its revenue exceeds a few million dollars per month.

Users primarily use VSCO to edit and process their photos before posting them on Instagram. If we were the VSCO product management team that saw this kind of use case, we would probably wonder, “If we already own the starting point of this user journey, then why not integrate it entirely into our service? Let the users edit and publish their images on VSCO, follow and talk to friends, and eventually view some ads.”

This kind of thinking probably pushed VSCO and a number of other photo editors towards making their own social networks, which, for the obvious reasons, had no chance of posing a threat to Instagram’s position, protected by the company’s strong network effects. At the same time, the reverse sounds quite possible: If Instagram decides to clone the popular editor and add its features to its own product, it will turn out just fine. However in most cases, social giants are not interested, with rare exceptions (we can think of adding MSQRD to Instagram, or Looksery to Snapchat).

How can we understand who has a stronger position in the value chain? This will require examining and understanding a particular market. In this study, it makes sense to look at who stands closer to the end customer, what are the defense mechanisms that different companies have, and what part of this value chain has a level of competition.

While the market is growing rapidly, the interests of all its participants in the value chain are usually aligned. As soon as growth slows down, the attention switches from outside to inside. At this moment, the players holding stronger positions begin to support their growth by expanding to new markets and capturing market share of other companies that depend on them. We have already discussed examples of similar behavior from search engines and Amazon. Here you can find a good analysis of the relationship dynamics within value chains for the PC and smartphone markets.

Examples of dependent players who have gained independence within their value chain

Value chains change slowly, but they change nonetheless. Sometimes the reason for this change is the shift happening in the world around us (i.e. the transition from the era of personal computers to the smartphone era), and sometimes it happens due to the competent actions of companies that allow them to change the balance of power.

For example, Booking.com was able to reduce its dependence on search traffic by creating a strong brand. Here is what Booking Holding’s CEO had to say about the SEO channel issue at the end of Q3, 2019, following the poor results of Expedia and Tripadvisor: “Regarding SEO, we saw some headwinds in the SEO channel that did create some modest pressure, but it’s a small channel for us.”

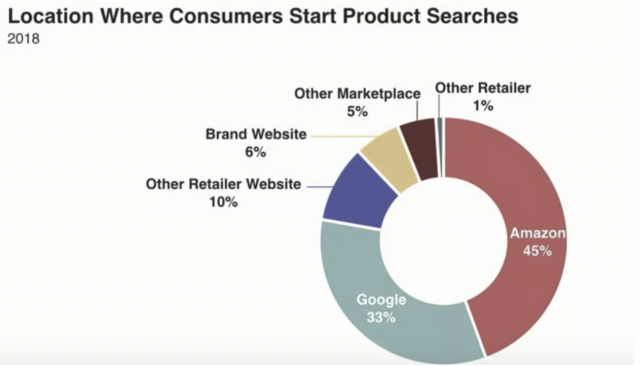

Another example is Amazon. Amazon is currently the main entry point for searching for goods in the US. The company accounts for 45% of all product queries, while Google’s share stands at 33%. Ten years ago, the situation looked totally different: Google was way ahead of Amazon.

Another source of change in the dynamics of relationships within the value chain is the way the world changes around us. For example, the rise of social networks has allowed artists and athletes to escape the control of producers, record labels, clubs, etc., and change the structure of their value chains. Previously, it was mainly the clubs/producers/labels who signed deals with sponsors, making them an essential part in any artist’s/athlete career. But now the system has altered, making the old players weaker. Artists and athletes have gained much more freedom and new opportunities to build direct relationships with their fans as well as brands and advertisers. But now, their dependency has shifted to social media giants.

Summing it up

Some companies, due to the nature of their first product, find themselves involved in a large number of value chains. This provides them with great opportunities to enter new business segments based on the foundation they’ve established. But there are some products that are self-contained, and for them, such a business expansion model turns out to be extremely limited. It might even be dangerous if the team mistakenly thinks there is an adjacent market where there isn’t.

Another important point is that one shouldn’t think of a vacant adjustment business segment as a call to action. The prospect of each opportunity should be evaluated in the broader context of other projects and their potential ROI.

Value chains are a great tool that allow you to look at your product or business from a new angle. It can help with the search for new growth points, as well as the identification of potential risks due to a dependent position from other companies in the value chain. Try to picture the value chain for your market and meditate on how your company, your partners and competitors are integrated into it. There is a high chance you might find something new.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.