In the previous essays of this series, we discussed how established companies and products can grow by entering new markets through movement into adjacent dependent segments in the value chain and building new products for an established user base.

Today we will talk about growing through expanding your product to new audiences. Here, the most typical growth paths are geographical expansion and movement up and down the market (B2C – SMB – Mid Market – Enterprise).

We will explore several examples where companies have successfully—and at times, not so successfully—used this growth path. We will also try to define a set of questions that will help to make a more informed decision about choosing this vector for a particular company.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

Launching a successful product for new audiences

One of the possible ways for a company to grow is to expand a successful product into new market segments. Here’s how it works:

The company has already invested a lot of resources into building a product that has proven its value for a specific segment of the audience. So why not launch the same product for other similar segments? Yes, there might be some adjustments needed, but the price seems to be rather small compared to the investments that the company has already made.

The two most common growth options of expanding a successful product into new markets are: (1) geographic expansion and (2) moving up and down the market (B2C – SMB – Mid Market – Enterprise).

Geographic expansion

Example 1: Uber proved its product’s value when they first launched their service in San Francisco. The logical move was to quickly scale up the working model and expand the product’s availability to other cities and countries.

Example 2: Airbnb was a huge success in New York. The logical assumption was that their model should work in other major cities as well.

Moving up and down the B2C – SMB – Mid Market – Enterprise chain

Example 1: Dropbox originally launched as a B2C product. But gradually, people started to use it to solve work-related problems. The logical step was to adjust the product for the needs of businesses and start selling it to this new segment.

Example 2: Slack initially had its big break among small tech teams and companies. Over time, the company began to purposefully move up the market towards the Enterprise segment, where the big money was. Many other companies are growing in a similar way in the B2B markets (in most cases, companies choose to move up the market, as the move usually promises higher margins, greater stability and higher LTV).

Each of the described paths has its pitfalls and risks. Below we will discuss a list of questions that will help you make an informed decision about whether this growth path fits a particular product under specific circumstances.

Important questions to ask when choosing a growth path

We already touched upon many of these questions in the last part of the series. In this essay, we will pay closer attention to the specific aspects of these questions in the context of each of the identified growth paths that involve launching a successful product for a new audience.

Q1: What is the added value of your product for a new market segment?

The fact that you have a working product in one market segment isn’t proof that the product will have substantial added value for another segment.

Most people will agree with this statement if you say it out loud. But when making strategic decisions about expanding the product into new markets, this issue usually eludes the management. Their confidence in the product, the apparent simplicity and affordability of entering a new market, and the obviousness of this growth vector nudge the question of the added value off the agenda. New markets, after all, are usually the low-hanging fruits of product growth and are an attractive first option for product teams.

When scaling geographically, the risk of lacking the added value is usually lower, but it is still there. In other markets (in other countries and cities), external conditions may differ (e.g., the market may be more competitive and advanced), which directly affects the added value your product provides. For example, in some of the regions where Uber made its debut, there were already local ride-sharing services that had captured a significant share of the market, which greatly influenced Uber’s growth and development rates.

In this article Andrew Chen answers the question of what he would have done differently if he could go back in time and start growing Uber once again:

“If you were to ask Travis, what would he say? He’d probably wish he had gotten into China faster. By the time Uber showed up Didi was already large. ”

In comparison to geographical expansion, when you are moving up and down the market, the risk of lacking the added value is significantly higher. The needs of B2C clients, small and medium-sized businesses, and large companies usually differ quite dramatically. Consequently, this complicates (and sometimes limits) the process of moving up and down the market.

As an example, hotel and ticket reservation services for corporate clients and mass consumers may have a similar technology at their core, but will differ in many other ways. For instance, serving large and medium-sized companies will impose the following requirements on the product:

- The possibility to set budget restrictions for different employees and different types of trips.

- Alternative terms of payment for services (e.g., delayed payments at the end of month).

- The fact that companies will pay bills with a delay (usually once a month, and not at the time the purchase is made) increases the risk of cash gaps and requires special mechanisms to control this type of risk.

The described differences may lead to a product being successful in one market (e.g., B2C) but lagging behind competitors in another (e.g., the SMB segment). Or a product that has found a product-market fit in the SMB segment may not be so relevant for enterprise customers. This is why the market is divided into several segments, and each of them follows its own laws and requires different product features, distribution channels and a pricing structure (more about this later).

This doesn’t mean that expanding along the B2C–SMB–Mid Market–Enterprise chain is impossible. But in most cases, it is much more complicated and expensive than it seems at first glance. At the same time, the cost lies not only in the necessary investments for adapting the product and the entire organization to a chosen new market, but also in splitting the teams focus between different directions.

However, in some cases, the added value of a B2C product for B2B customers comes out organically, such as when customers start using a B2C product for their business purposes. In this case, the transition turns out to be much more natural, both at distribution level and at the modifications that need to be done to the product itself. Dropbox and Miro are good examples of this strategy.

Q2: How does the value chain of the new market compare to the current value chain?

The value chain reflects how different companies interact with each other to create a product aimed at satisfying the final demand in a particular market. Feel free to read more about value chains here.

In the previous part of the series about growth through the launch of new products to the current audience, we explored how the mismatch between the value chains of the new product and the current business of the company is an obstacle that few can overcome. Even tech giants with literally unlimited resources often encounter complicated issues because of this mismatch when expanding to new markets.

Value chain mismatches are relatively rare in geographic scaling. In most cases, when choosing new cities or countries to launch in, the company’s management intuitively seeks to choose regions with a similar market structure, i.e., they look for a similar value chain.

But that is not always the case. For example, when Western gaming companies try to launch a successful game on the Chinese market, they need to learn to work within the new value chain with other app stores, payment methods, and growth channels. Similarly, if the business is strongly tied to the real world (for example, in cases like Uber or Revolut) in new countries, you will have to adapt to local realities and regulations, as well as build new channels to acquire drivers, and sometimes customers.

With geographic expansion, the problem of changing the value chain is usually visible on the surface, so it rarely comes as a surprise to the management. But when moving up or down the market, the problem is often concealed. So, during the decision-making stage, the management rarely realizes the complexity and the amount of resources that need to be allocated when adapting the product to the new market segment.

Here you can read an essay by Brian Balfort, in which he reflects on why companies often fail to move up and down the market.

Large SaaS markets portray the fundamental processes underlying these failures. In most of these markets, we usually observe several large companies with products that are very similar. However, each of these companies operates in its own segment (SMB, Mid Market, Enterprise).

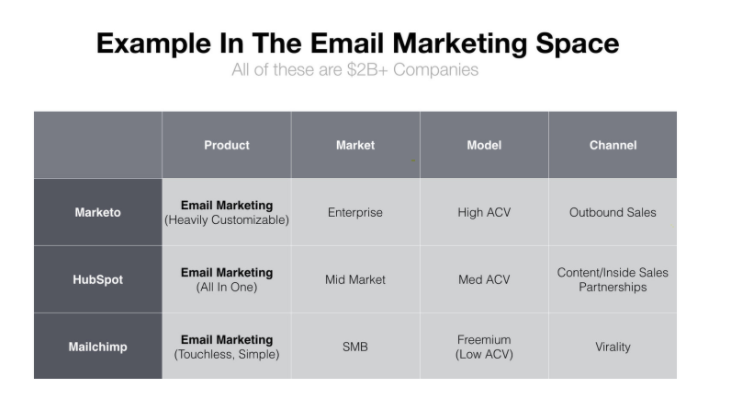

For example, if we look at the email marketing space we will see the following:

- Mailchimp has occupied a small business market segment with a simple product, a freemium monetization model, and organic and viral growth channels.

- Hubspot has come up with a product that combines many tools. They target medium-sized companies that they reach through a combination of content marketing and internal sales.

- Marketo is a classic product aimed at the Enterprise market, which is distributed through the sales team.

The technology and product foundations at the core of each of the above companies are not really different. Then why does each of them exist only in its own market segment and hasn’t captured the entire market? And why do we see a similar pattern in all SaaS markets (you can find more examples here)?

The reason is that different segments of the same market often exist in different value chains. Value chains are the ones that define boundaries for companies, and not the technology or the task itself. To move to an adjacent market segment, you need a modified and adjusted product, new distribution channels, a new business model and pricing structure, and a different team expertise.

If the market you want to expand to exists in a different value chain, then you need to study this value chain and honestly evaluate the investments necessary to adapt the current product, company structure and other processes to this market. You also need to honestly answer the question whether all of this has any conflict with the things that have already proven their worth and efficiency, with what your current business is built around.

Q3: What is the marginality and growth potential in the new market segment?

If the goal of the team is to increase profit (or revenue), then it is only natural that projects with a higher margin (or those that have bigger growth potential with the same amount of investment) will receive more resources and attention at the planning, resource allocation and decision-making levels. Projects with a low margin (those that have smaller growth potential) will end up at the bottom of the priorities list, i.e., won’t be executed.

Therefore, when developing a plan to expand a successful product into new market segments, it is important to evaluate the higher margin of the business in the new market segment, as well as its growth potential. If it turns out that the new market doesn’t look good according to these characteristics, then at all company’s levels where the resources are limited (which posts get more impression on the social media app on the social network, specific shelf space allocation in the supermarket, sales team resources, developer resources), the project will be considered low-priority. If you are the CEO, you have the power to choose a certain direction to grow, but if the goals of the organization system contradict with it, the project will decay.

A possible solution to this problem may be to allocate a separate team that will launch the product in the new market segment. But quite often, due to the already existing product, the technology and other inevitable intersections within the processes, it will be practically impossible to achieve the independence of the two teams.

In most cases, the described processes neutralize the chances of success when companies choose to move down the market, since in this case the margin usually decreases. Therefore, in the vast majority of cases, companies try to move up the market. This migration up the market in search of higher margins and growth is one of the fundamental forces underlying the Innovator’s Dilemma, which Clayton Christensen described in his book Innovator’s Dilemma and Innovator’s Solution (highly recommended).

There are instances of companies successfully moving down the market to segments with lower margins, but they are few and far between. We can think of Uber, who originally started from the premium segment (Uber Black), where the company was making sure the technology behind it works, and then moving to the mass segment of the market with UberX and UberPool products.

Q4: Is the organizational structure of the company ready for expansion to new markets?

We have already considered a number of aspects that must be taken into account when expanding to new markets. Several times in the process, we’ve directly or indirectly raised the question of how effectively can the team implement and support the required changes.

For example, during its geographic expansion, Uber management built a local team for each new market where they launched. These teams took on a number of functions specific to a new city or country where they were launching. In most cases, the new market required new mechanisms for driver and passenger acquisition, as well as adaptation of processes to legislation and market regulations, local support, etc. Meanwhile, the main product was developed centrally.

The described model worked well during geographic expansion for Uber and a number of other companies, where the product doesn’t require any radical changes to adapt to the new markets. But there are counterexamples as well, such as Ebay’s failure to launch in China. The company began investing in China in time with the rapid growth of the country’s online commerce market. Ebay even became the market leader in the early stages of its development there. But it eventually lost the race to Alibaba and JD.

Ebay’s key problem turned out to be its inefficient organizational structure, where most of the product and tech-related decisions were made centrally in CA. As a result, important projects for the Chinese market failed to make it to priority lists, which eventually led to local competitors overtaking Ebay. You can read more about this failure’s story in “Alibaba: The House That Jack Ma Built”.

Summing up

Extending the product into the new markets is one of the classic ways for companies to grow. Most often, we can see it in a way of geographical expansion to new markets or in moving up and down the market along the B2C – SMB – Midmarket – Enterprise chain.

Scaling geographically is quite a challenging task. However, it has the benefits of having predictable expenses, complexity and volume of the work needed. Therefore, if there is proper management quality at hand, most teams successfully cope with this challenge.

When moving up and down the market, there are many risks that remain hidden from the team’s view at the planning stage, making the task look much easier than it actually might turn out to be. When choosing this growth path, it makes sense to invest more time and resources into studying the market segment you choose to enter, as well as to assess the amount of possible changes and the necessary investments.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.