Watching new and rapidly changing markets can teach you many things. The work communication market led by companies such as Slack, Microsoft Teams, and Workplace by Facebook is something I have been following for a long time.

Last year, before Slack went public, I did an analytical review of the data disclosed in Slack’s S-1 filing. At the end of that review, I shared my opinion that Slack experienced problems in the enterprise segment: the competition from Microsoft Teams and Workplace by Facebook for this market segment threatened Slack’s long-term growth prospects and its $20+ billion valuation.

A lot of things have happened in the eight months that have passed since I published that essay. A lot of new data has surfaced, with one of the biggest market intrigues fading away and a new one appearing. The leading characters once again reminded us of a number of fundamental rules the market plays by. And this is exactly what I am going to talk about in this essay.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

The facts about the race between Slack, Microsoft Teams, and Workplace by Facebook

Microsoft Teams was introduced to the market at the very end of 2016 and became available globally at the beginning of 2017. At that time, three-year-old Slack’s DAU already amounted to more than 4M users, which is an impressive number for a young startup in the B2B segment.

By mid-2019, Microsoft Teams took the lead in DAU, and by the end of 2019, Teams had outrun Slack with their 20M DAU versus Slack’s 12M (almost double).

It is not only about how fast Teams was able to catch up and then take the lead, but how dramatically the growth rates of the two products differ.

A good proxy of the new users’ dynamics of Slack and Teams is their app download figures. In my experience with Workplace by Facebook (I worked on Workplace by Facebook for a few years, but I am not working on it now), the new users of these services either install apps within the first few days or don’t install them at all. Therefore, the dynamics of the number of downloads of the apps should correspond to the dynamics of new users coming to the services (mind that this is not entirely true for older products due to the significant effect of the old users downloading apps again when they purchase a new phone).

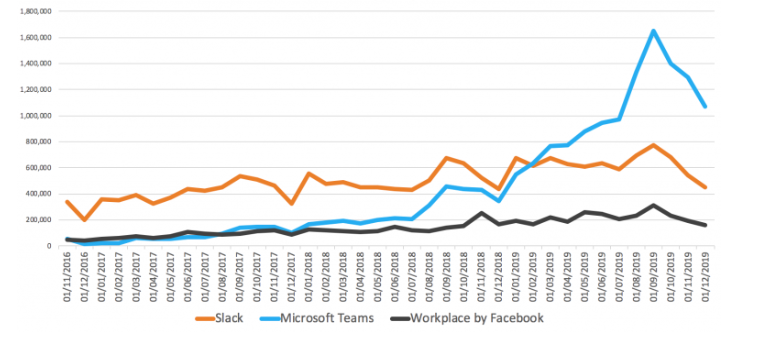

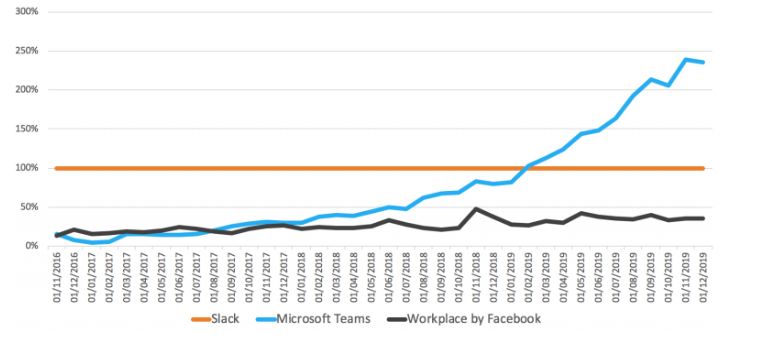

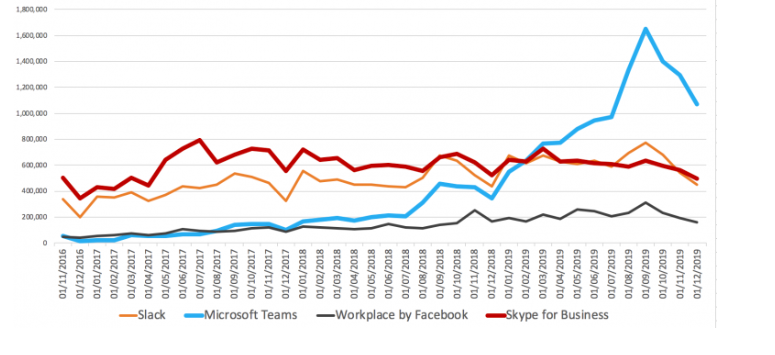

Below you can see the dynamics of Slack, Teams, and Workplace mobile app downloads over the past three years (since Team’s launch). I used the data from a great service called AppMagic.

On the pic: Slack, Teams, and Workplace apps downloads’ numbers (according to AppMagic)

The image becomes clearer if you scale the graph to set Slack’s downloads as the baseline (see below).

In 2017, the number of new users downloading Teams and Workplace was fairly comparable. Both of these services were gradually catching up with Slack but were still lagging far behind in terms of the number of new users (keep in mind that Slack had already had about 4 million DAU at the time its competitors launched).

In 2018-2019, Workplace continued to increase the number of its new users faster than Slack. Currently, Workplace monthly downloads numbers make 35-40% of Slack’s downloads.

In 2018, Microsoft Teams started to leave Workplace well behind and gradually closed its distance with Slack. By the end of 2018, Teams had caught up with Slack, according to the number of downloads per month. Shortly after, it flashed past Slack and left it in the dust. Presently, the Microsoft Teams app gets 2.5 times the downloads that Slack gets. The observed dynamics correspond to what we saw in the DAU’s chart above.

It is worth noting that, due to the fact that Slack tends to thrive in the technology segment of the market, it is likely that the proportion of users who download Slack’s app is higher than that of Microsoft Teams and Workplace. If so, the gap between Teams and Slack in terms of new user numbers is even greater than shown in the graph below.

On the pic: Slack, Teams, and Workplace apps downloads’ numbers scaled to Slack’s numbers (according to AppMagic)

Slack’s stock price began to tumble right after going public. You can see the sharp drop in the stock value right after Microsoft announced the DAU numbers for Teams in September of 2019. Now Slack’s valuation has plateaued. It is currently estimated at $12-13B (the value reached $20+ B at the moment of their direct public offering).

How did Microsoft Teams grow so fast: Understanding the importance of controlling distribution channels

What allowed Microsoft Teams to boost growth and outrun Slack in such a short period?

Was it the product dominance? Not really. Instead, it was Microsoft control of distribution channels that delivered the product to its massive customer base.

I have three hypotheses about which growth channels accelerated Microsoft Teams’ growth:

- A deeper and more aggressive integration with Office 365;

- The migration of Skype for Business users to Microsoft Teams;

- The launch of the free version of Teams in July 2018 for small and medium-sized businesses, and the subsequent growth via word-of-mouth.

Judging by publicly available data, here is what I think. The main driver behind Microsoft Teams’s growth is the deep integration with Office 365. Most likely, we also observe the early results of the users migrating from Skype for Business to Teams. I suppose we will be able to see a more vivid effect of this process next year.

Let’s discuss each of these hypotheses in detail.

Integration with Office 365

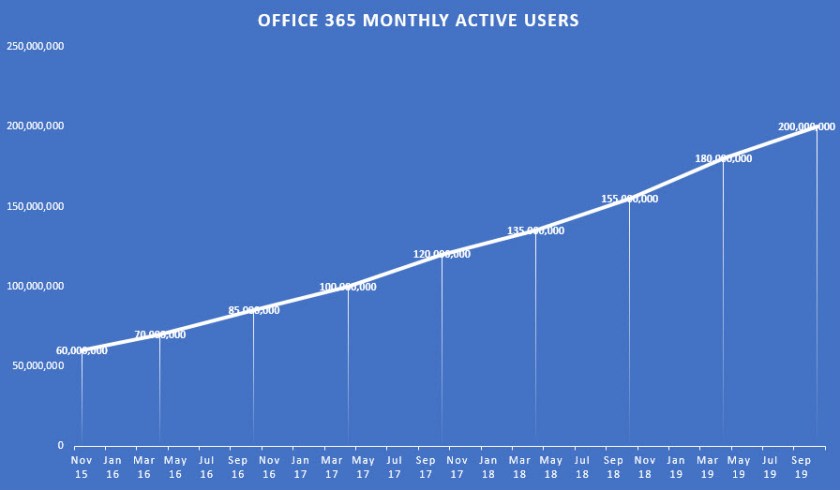

Microsoft products are deeply integrated into the workflow of many companies in the world. The audience from Microsoft Office 365’s main product (a bundle with all the Office products, such as Excel, Word, Powerpoint, etc.) surpassed 200 million MAU users by the end of 2019.

Office 365 also includes ProPlus, a special service that allows tech departments of any organization to install Microsoft services on their employees’ computers, as well as control the frequency with which the individual products within bundles are updated. Some of these products fall into the Monthly Channel (monthly updates), others fall into the Semi-Annual Channel (updated every six months).

In mid-2019, the Teams product was included in the Monthly Channel for the new version of Office 365 ProPlus. This meant that in companies using the new version of ProPlus, Teams would be installed on employees’ computers automatically with the next monthly update.

Microsoft spent a year and a half polishing the Teams product. Once it was good enough, the company began to gradually introduce it to its customer base through its powerful distribution channels.

After hearing about this, Slack representatives were quick to announce that Microsoft Teams overestimated their DAU numbers by including such pre-installed Teams’ clients.

But this is not the case. The documentation clearly states that an active user is one who explicitly performed an action such as sending a message, making a call, starting a chat, etc.

“We define DAU as the maximum daily users performing an intentional action in the last 28-day period across the desktop client, mobile client, and web client,” said Microsoft Vice President Jared Spataro. “Examples of an intentional action include starting a chat, placing a call, sharing a file, editing a document within teams, participating in a meeting, etc.”

Migration of users from Skype for Business to Microsoft Teams

Skype for Business corporate chat came to life in 2015, becoming a replacement for its predecessor, the Lync messenger, whose audience exceeded 100M users at the time. The new product combined features from Lync and Microsoft’s recent acquisition, Skype.

On September 25, 2017, Microsoft announced that Teams would at some point replace Skype for Business. Last year, the company saved the date: Skype for Business will no longer be available for new organizations starting from July 31, 2021, which is a year and a half from now. But until this date, the Teams’ product will live completely separately and won’t affect Skype for Business in any way.

Most likely, some organizations have already started the migration, which may impact Teams’ growth rate. However, this process is currently organic and is not forced by Microsoft at all. Given the end date for Skype for Business, we can expect that the migration process will only build up its speed, and is likely to become the second powerful driver for Teams’ growth next year.

The absence of any forced transfusion of users from Skype for Business to Teams is also evident in the dynamics of mobile app downloads for the products: Teams’ rapid growth hasn’t affected Skype for Business downloads at all.

On the pic: Slack, Teams, Workplace and Skype for Business apps downloads’ numbers (according to AppMagic)

The launch of Teams’ free version

In July 2018, Microsoft launched a free limited version of Teams aimed at small and medium-sized businesses. Despite the fact that the launch coincided with the first jump in the number of Teams app installs, I don’t think that the free version was the main driver of their phenomenal growth in 2019.

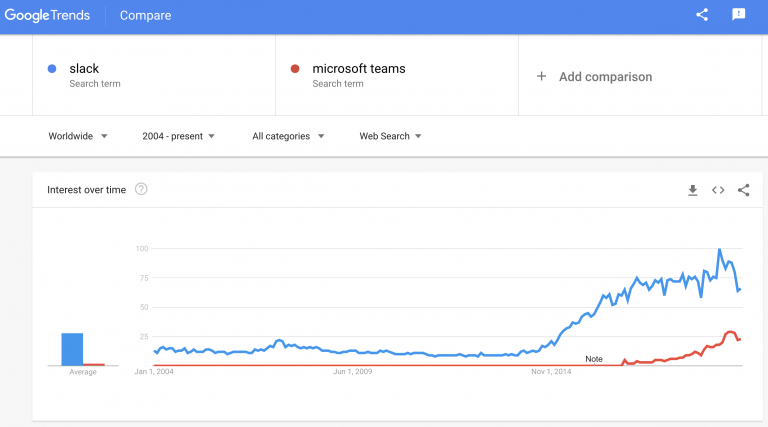

The main growth channel in the SMB market is word of mouth. I explained in detail how it works in a previous Slack’s review. Despite growing interest from the market, Teams loses much to Slack in terms of organic interest in the service, fueled by word of mouth (based on Google Trends). It is also worth noting that the numbers for Microsoft Teams might be underestimated in the graph below since many users can search for a product by simply typing “teams”. However, it is impossible to distinguish those who are looking for the service from the ones simply using the same word for their query.

I think that Microsoft launched Teams free version outside Office 365 (for Office 365 customers the product was already a free addition to the general bundle of services), in order to simply tick all the boxes and meet the industry’s standard, covering all the potential audience segments. But I don’t believe Microsoft is that much into the SMB segment because it has traditionally drawn most of its value from contracts with large corporate customers. I might be wrong, though.

In Slack’s case, the focus on SMB segment and corporate teams is part of their unique bottom-up growth strategy, a stepping stone toward attracting large companies. This strategy has worked to a degree and some large teams have already started using their product.

But Microsoft already has large corporate customers and it doesn’t make sense for them to use the same tactic to reach customers with whom they have already built a relationship. On the other hand, Microsoft might have wanted to win back the SMB segment, which they had previously lost to Google’s G Suite product.

Slack will continue to grow, but won’t become the market leader

Slack ushered in a new generation of messengers for teamwork. The product quickly proved that it creates significant added value over email and other general-purpose messengers (such as Skype), which took over users’ hearts in most tech and media companies.

Slack built an effective growth machine by using its bottom-up model: Using word-of-mouth, the free version of Slack finds a foothold in teams and then starts to grow inside companies (sometimes organically, and sometimes with the help of Slack’s sales team, and sometimes in both ways simultaneously).

These two innovations provided the foundation that allowed Slack to create a new market and become its dominant player in the tech corporate messenger segment.

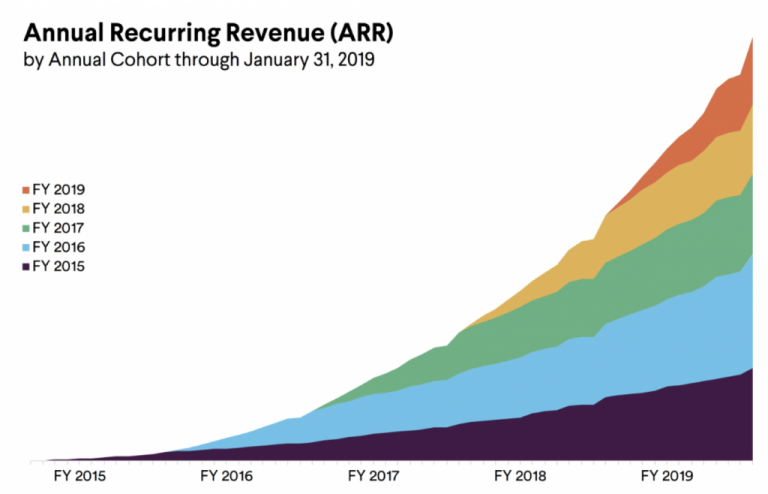

A similar growth model has also become the foundation of a sustainable business model with a negative revenue churn. This means that older customer cohorts pay more over time. This happens due to Slack’s increasing over-time penetration in organizations where someone has already started using the service, as well as due to these companies’ growth. You can read more about it here.

The creation of a new product type, the leadership in the tech niche, and most importantly, a growth model that was not dependent on the size of their sales department made it possible for Slack to build a fast-growing multi-billion dollar business and drew the attention and interest of huge investors in Slack as a company.

Yet when the company went public its valuation was mostly based on its future growth potential, particularly in the Enterprise segment ($28B a year, according to the Slack team’s estimates).

Much of Slack’s S-1 filing was dedicated to demonstrating how Slack is successfully expanding into the Enterprise segment and how well the current growth model provides a launch pad for this process. Here’s what the Slack team said in the S-1 filing:

“We offer a self-service approach, for both free and paid subscriptions to Slack, which capitalizes on strong word-of-mouth adoption and customer love for our brand. Since 2016, we have augmented our approach with a direct sales force and customer success professionals who are focused on driving successful adoption and expansion within organizations, whether on a free or paid subscription plan.”

Slack was too slow to conquer the market and had no built-in protection mechanisms

This is where the most interesting things surface.

By the time of its IPO, Slack had a working growth model, but in the six years since its launch, this growth model provided the product with no more than 5-6M paying users. It doesn’t sound too impressive if we compare it to Office 365’s 200M paying users, or Skype for Business (or Lync, if we are talking about way back) with its 100M users.

Slack had a very small market share at the time of its IPO filing, while its main growth potential lay in the Enterprise segment. The key question was whether Slack could transform its growth model and capture the market before Microsoft or Facebook made their move.

Here is what I had to say on the matter eight months ago:

“Microsoft already has access to a lot of large enterprise clients from all verticals and has been selling them products bundled in a single package for a long time. They recently added Microsoft Teams to the Office Suite, which is just as good as Slack in terms of functionality. Does Slack offer enough incentive to convince enterprise customers to forgo the benefits of their long-term relationship with Microsoft? ”

And now at the beginning of 2020, it seems that we have an answer to the above question. Slack, most likely, won’t become the leader of the market it has created:

- Microsoft Teams is already twice as big as Slack (20M DAU against 12M).

- By the end of next year, it seems the gap will be much bigger. Microsoft has just begun making use of its distribution channels.

- Microsoft’s distribution channels reach out to all industries, which will allow them to deliver the added value of a new generation of working messengers to markets that Slack hasn’t reached out to yet.

- Microsoft offers Teams to their customers for free (as an addition to Office 365). Even if Teams loses to Slack in terms of product experience (I personally don’t buy it if we talk about the world outside Slack’s home tech market), the price factor will make many organizations choose Teams over Slack. For this reason, the statement by Slack’s CEO that 70% of Slack customers paying over $1M a year are Office 365 customers sounds more frightening than encouraging.

Slack didn’t give up and tried their best to resist Teams

Slack is increasing its marketing and sales budgets. The company invests a lot in increasing its penetration in companies where teams have already started using their product. To do so, they even offer large companies the offer to pay for 1,000 annual licenses and get the rest of the licenses for free. But all of these measures don’t stand a chance to what Microsoft has up its sleeves.

After announcing last quarter’s results, Slack’s CEO mentioned that the Teams audience is less engaged than Slack’s, which won’t allow Teams to achieve the same effect that Slack has on teams and organizations.

Teams’ audience might not be as engaged as Slack’s. However, if a company has already switched to Teams, this fact blocks the path for any other direct competitor, in this case Slack, to enter this company. Slack’s added value pushed many users of email and Skype for Business to switch to it. But when comparing Slack to Teams, the differences are not enough to trigger the same effect at the team or company level.

Microsoft was quick enough to notice the startup that began to carve itself a niche in its market by capturing the use cases previously fulfilled by email or Skype for Business. Microsoft decided to create their competitor’s twin and use it to kill Skype for Business and partially Outlook on its own instead of allowing Slack to do it.

This is not the first time Microsoft has played this game. We can think of Internet Explorer vs Netscape, or Lotus/WordPerfect/Harvard Graphics vs Excel/Word/PowerPoint.

The scheme “default + good enough” still works just fine.

New intrigue within the race: Workplace by Facebook and Microsoft Teams fighting for “Firstline Workers”

In January 2019, Microsoft released a product update, where all the new features were aimed at first-line workers (sometimes they are called frontline workers).

First-line workers are employees who are at the forefront and are responsible for communication with clients (e.g., salesmen, waiters, cashiers, delivery, etc.). These people usually belong to the deskless workforce, thus, they do not have their own workplace, computer, etc.

Frontline workers have never been among Microsoft customers before. Most of them don’t even have an email account, since the cost of such an account would have been financially unjustified. Outlook, for example, costs $4-12.5 per month per user.

Such a change in product’s focus can be considered a signal that the Microsoft team is pleased with the results of protecting its borders from Slack’s attack, and is now ready to expand Teams onto the new markets.

And this is where a new intrigue comes into the spotlight. This time it’s between Microsoft Teams and Workplace by Facebook.

Key facts about Workplace by Facebook

Workplace by Facebook was publicly launched in October 2016. In February 2018, Workplace announced they had 2M paid users, and only 8 months later they claimed the figure had grown to 3M.

Workplace is not a direct competitor of Slack or Teams. Workplace serves a much wider function, connecting people from different teams and parts of the organization. Most of these people would have never talked to each other under normal circumstances (for example, employees of different Starbucks coffee shops). It is worth noting that Workplace also has chat for teams, but this is only one of the product’s many features.

Workplace targets large organizations, most of them located outside the tech sector. Its customers include Walmart, Starbucks, AirAsia, and many other large companies.

If you look at Workplace customers, you can see that the product resonated with the companies whose first-line workers are very numerous. Knowing that, the fact that Workplace is choosing to move in this direction from a product point of view can’t be an accident.

“Today we’re announcing new Workplace plans: Workplace Essential, Advanced, Enterprise, and a Frontline add-on. These plans will help organizations to connect frontline workers with the rest of the business, predict costs, and choose the tools they need,” said Facebook vice president Julien Codorniou in a statement in 2019.

In addition to this, Workplace is trying to solve the problem of integrating first-line workers into the company not only from the product’s side but from the business side as well. They even presented a special tariff for the first-line employees, which is much less expensive than the standard plan: It only costs $1.5 per active user.

Microsoft Teams and Workplace by Facebook’s fight for the first-line workers segment

The first-line market segment is a great opportunity. According to Gallup, today there are 2.7B first-line workers in the world and only 13% of them feel engaged at work.

This market segment has historically been deprived of communication tools, making such employees detached from the company they work at. A product that solves this problem will create a significant added value.

I find the current confrontation in this segment of the company communication tool market very intriguing. The starting lineup looks anything but boring.

Microsoft has no clear advantages in this market segment. First, they still need to prove that their current product can create value for first-line workers. Second, their current distribution channels don’t reach first-line workers (they don’t use computers, which means they don’t have Office 365 accounts). Most likely, Microsoft won’t have trouble reaching companies with first-line employees. But once they do, they will have to come up with something new to reach the end users. Third, the battle will take place on the smartphone battleground, not personal computers. And as far as we know, this has never been Microsoft’s forte.

Workplace stands in a more promising position to win this market. Workplace has already shown that its product creates value for first-line workers: their successful case studies include Starbucks, AirAsia, Walmart and some other big names. Workplace also has the advantage of not requiring any workshops to master their product (everyone is already using Facebook anyway, which means that the interfaces and Workplace features will be familiar to its users). Perhaps Workplace’s other advantage is that this market segment is already using Facebook tools to solve its business-related tasks (using Messenger, Whatsapp, Facebook Groups). This is only a hypothesis, but even if it is true, the task of transferring such ad-hoc and unconventional use cases to a new specialized product is yet to be solved.

Summing up

Slack has redefined the business messenger market, has found a unique and working growth model, and has built a decent brand. This was enough to create a multi-billion dollar company, but it wasn’t enough to become the leader of the new market.

Teams, which can be called a free doppelganger of Slack, currently distributed across Microsoft’s client base through well-established distribution channels, has already outrun Slack’s DAU numbers by a factor of two. Next year, the gap is likely to grow.

I think that at this point the battle between Slack and Teams is over. Microsoft has once again reminded us that without strong network effects or other powerful protection mechanisms, control over the distribution channels remains one of the main success factors.

After showing Slack who is the best, Microsoft is off to conquer the first-line workers segment, which has been deprived of any attention from the key tech players for many years. Here, the standoff will be between Teams and Workplace to win a 2.7B user market. Both products currently hold similar positions. I might even say that Workplace may have a slight advantage here. However, both of these companies are just starting to pave the way, so the best drama is yet to come. Stay tuned!