GoPractice spoke with Dmitry Vasin, the Product Owner of the Revolut Trading from 2018 to 2020. Revolut is a leader in digital banking. At the beginning of 2021, it was the largest digital bank in Europe with over 15 million users and ~$5.5 billion valuation. During this period, Dmitry helped develop and launch the product.

Dmitry told us about the specifics of creating and developing a product in a strictly regulated market:

- Why it is important to involve people with solid industry knowledge in product development

- Why and how to combine a conservative approach with the desire to innovate

- How regulation affects the work of a product manager.

In the conversation, Dmitry discussed the mistakes his team made at different levels—technical, legal, product—and the lessons he drew to avoid such mistakes in the future.

For the convenience of the reader, we present the material in Q&A format. We also divided the conversation into two chapters and a brief conclusion.

The first chapter gives a general idea of the trading product from Revolut: what is its value, how it was launched, what it achieved in the market. The second chapter discusses the details of working in a strictly regulated market. In the summary, Dmitry provides some recommendations and reflects on what he would have done differently if he were to start from scratch.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

Chapter 1. Revolut Trading: Idea, Value, Launch

GP: Tell us what you achieved with Revolut Trading. Was it a successful product?

We launched in August 2019, and in the first six months, we reached an audience of 500,000 users, putting our platform ahead of our direct competitors. For example, the Freetrade service launched a few months earlier than we did, but by the beginning of 2020 their audience reached 300,000 users. Trading 212, which at that time was more than three years old, had an audience of about 400,000 users .

Now the audience of Revolut Trading has surpassed 1 million users. This doesn’t mean our competitors are inferior. Trading 212 now has an audience of almost 1.5 million users.

GP: How did you come up with the idea to develop an investment product in Revolut?

The idea itself was inspired by Robinhood. They had made an app that allowed American users to trade stocks easily and for free. The company was founded in 2013 and launched the app in 2015. By 2018, Robinhood had reached an audience of 4 million users and was valued at $5.6 billion. Today, experts estimate Robinhood’s valuation at $20–40 billion.

Revolut is a leader in digital banking. At the beginning of 2021, it was the largest digital bank in Europe with over 15 million users and ~$5.5 billion valuation. It was Nikolai Storonsky, Revolut’s founder, who came up with the idea to provide an investment platform to the company’s users. I was hired to implement it.

Prior to Revolut, I worked as a Technical Product Manager in the mobile app department of Tinkoff Bank. I had no experience in developing trading services, but I had already used investment products to purchase shares. During the interviews at Revolut, the HR joked that since I have physics and tech backgrounds, I’ll figure it out. Well, I’ll tell you now about how I figured this whole thing out.

The essence of the Revolut product idea was to make a tool for buying and selling stock in a way that would be understandable and accessible to a mass user base in Europe. At that time, most of these tools were complex and designed either for professional investors or for those who were ready to go big. In addition, people needed to invest time to understand tools like marker order, limit order, stop-loss order, and so on.

The goal of Revolut Trading was to create a product that people with no investment experience and knowledge could use to start investing in stocks.

GP: You had Robinhood as a successful example. Why didn’t you just copy them?

Robinhood gave us many ideas for what an investment product for newbies should look like. But this is just the tip of the iceberg. The devil is in the details.

A big part of an investment product is processes that are hidden from the user’s eyes, and these processes are specific to different markets due to different laws and regulations. For example, due to differences in regulatory policies across countries, Robinhood’s business model couldn’t be implemented in the UK (it is illegal there). Because of this, Robinhood hasn’t entered the British market yet, though they have announced plans to do so.

Another feature is the specificity of the market and the customers. According to our calculations, only 15-20% of residents in European countries were inclined to use investment services, while in the United States, this figure reached about 50%. This difference also had to be taken into account when developing the product. Robinhood could afford to simply provide an interface for buying and selling stocks. They could avoid providing information about stocks in the app, because people understood what stocks are and how they could Google the necessary information or use other tools to learn more about them. We needed to work with an audience that stood at a completely different level.

In the UK, many people need basic, very simple products. The need of basic information about investment here is significantly higher than in the United States, but not as high as, for example, Russia, where only about 5% of residents are inclined to invest. For this reason, “Tinkoff” was forced to prepare good information units, tips, all kinds of recommendations, essays in their blog and other useful bindings.

GP: Can you briefly describe the state of the market and what value you wanted to bring to it with your product?

The main hypothesis of the product’s value was that we can make investing simple and convenient for amateurs and beginners. We wanted to popularize and democratize investing into stocks.

There are many brokers in the European market that allow you to buy and sell stocks, but their solution is not suitable for newbie investors.

Some of them charge fairly high commission rates on trades. For example, an IG broker in the UK charged £4-5 per trade. If the user only wants to buy a few Tesla shares, such a high commission becomes an obstacle. Other brokers require users to make a large deposit upfront.

We understood that as soon as we offer a freemium product—that is, no commission, at least on the first trades—as well as remove any requirements for minimum investment, we will minimize barriers to purchasing shares and will create significant value compared to other products on the market.

Focusing on newbies also required some product-level simplification. Professional traders use desktop monitors and see a lot of information. In contrast, amateur investors will mostly do their trading on their smartphones, which doesn’t have much display real estate. Therefore, we had to learn how to convey complex things in simple language and remove what we can do without.

The expected result was a product in which everything is built around the Buy and Sell buttons. There is a card, an account with money, and this money can be easily exchanged for shares. There was no need for the user to understand what is happening under the hood, such as through which broker the connection to the exchanges goes, where the market data is delivered from, who is custodian, and so on.

GP: Were there any similar products? Was there someone preparing to launch a similar product at the same time as you?

Of course, we were not the only ones who decided to build an investment service for newbies in the UK; we had direct competitors. For example, Freetrade launched shortly before us. We also looked at the experience of companies such as eToro, DEGIRO, Plus500, Trading 212.

But we had a significant advantage. It was much easier for us to reach our audience because we were targeting existing Revolut users. Early on in development, we interviewed them, identified their needs, and tried to get the basic functionality up and running as quickly as possible.

GP: What did the product launch look like?

Revolut Trading product was launched as part of the main Revolut app. And at the time of the first release, Trading was hidden on the very last screen of Revolut behind the “More” tab. Moreover, the product was available only to users on the most expensive version of the subscription – Metal.

We launched at around 3-4 am. The developers turned on the Trading feature—after 30 seconds or a minute, the first users started registering within the service. We hadn’t made any announcements, broke the news or posted banner ads yet. The promo started only in the morning and during the next day.

This is how we launched the product on August 1, 2019. And so we realized that the audience is interested in it.

GP: How did you rate the success and value of the service after its launch?

Inside Revolut, there were (and still are) several levels of subscriptions, from standard free to advanced paid. The most expensive of them is called Metal, which is where we launched Trading. This decision pursued the following goals:

- Give Metal subscription users more service and value;

- Increase conversion to Metal from other subscriptions.

We monitored the influx of new Metal subscribers and observed a 40% increase in the first week after the launch of trading. This was an impressive number and told us that users were willing to pay for this service, and that was the success metric. Later, the product became available to all users, but we introduced special limits on simpler subscriptions.

In terms of business metrics, our goal was for 10% of Revolut’s MAU to become Trading users in the next year. If we break it down by months, then in the first month we expected 1-2%. After the launch, we saw this number and were very pleased.

Another signal that the product was creating value was that long-term retention was plateauing. After three two-week intervals (that is, about 5-6 weeks), retention curve plateaued at 30-35%. We calculated retention based on having at least one trade in Revolut Trading .

I calculated Retention based on the two-week intervals, since that was the average frequency of using the product for most users. The product was not meant for frequent use, i.e., targeted at traders who constantly trade (generally, it’s not very convenient to carry out such activity from a smartphone app). 80% of our users came in about once every two weeks to buy and sell something.

All of this indicated that people found value in the product and continued to get this value on a regular basis. Moreover, the product was in demand among the Revolut audience, which meant we created business value for the overall ecosystem.

GP: Did you manage to reach the target audience – newbies and non-professionals?

I think we did.

About 40-50% of Revolut Trading users at that time were people who had never invested before and made their first trade with us.

We reached this conclusion through two methods. First, we conducted polls in which users stated their experience, but as we know, users might not tell the truth. Second, there was an indirect method that helped us. Usually, those who have been trading for 2-3 years or are well-versed on investing have questions about accounts with tax benefits.

At some point, we even had a hypothesis that without these accounts (ISA – Individual Saving Accounts), we risked scaring off a significant part of users and not achieving any success. But it turned out that there wasn’t so much demand for this among the newcomers.

We managed to hook an audience that our competitors failed to attract. We achieved this precisely through the values that we initially had: to make the product as simple and accessible as possible for everyone, and not just those who already know what trading is.

GP: Who were the rest of the users?

Some of the users came from other services, such as eToro or Freetrade, because we don’t charge commissions on the first transactions. They were looking for a specific stock and they chose us because there were no extra charges.

Others came to Trading because they were already Revolut users and chose the convenience of keeping all their money in one place. It is much more convenient to have access to various financial services in one app instead of ten. On Revolut, you can get your salary, your insurance, your children’s accounts, transfers, convenient withdrawal of funds, and so on.

Revolut was fortunate that it already had an audience to offer the trading to. If you had to run a stand-alone app, it would be much more difficult to attract an audience. And this is a very strong advantage over Freetrade in the UK.

I’m focusing on the UK because UK users accounted for about a third of our audience. The rest were from other European countries.

Interestingly, Poland, for example, is not the largest market for Revolut, but there were a lot of Trading users from there. We started to find out why: it turned out that there are simply no other decent trading products in Poland.

GP: To the reader, it might seem like everything went smoothly and according to the plan. Was it really so?

Of course not. We faced many problems while creating and launching a product. Many of them were related in one way or another to regulatory risks (note by GoPractice: we will discuss regulatory challenges in the second part of this interview).

But some of the problems were mainly on our side.

For example, we were unable to properly onboard [Revolut CEO] Nikolay Storonsky, and he got very angry. The reason was that the KYC (know your customer) rules for onboarding in Revolut had changed in the previous two or three years, so for some old users part of the needed information was missing.

In such situations, we had to request the additional data from the customer, which roughly meant to take them through the KYC process again. This problem affected about 10-15% of Revolut users.

This caused some pain, because the users of the Metal subscription—and even more so some of the very first users of the bank, of course—expected a certain level of service, and when Trading was not available to them, they were unhappy about it.

Chapter 2. Lack of Industry Knowledge: Errors in Legal Design and Product Architecture

GP: It came as a surprise to you how strongly all processes were influenced by the fact that the product was created in a strictly regulated area. Tell us about it.

True. We ran into problems because of this issue and it affected the product and growth at almost all levels:

- Legal: we built an imperfect scheme and lost a lot of time trying to implement it

- Marketing: we had very limited advertising opportunities

- Monetization and business model: we couldn’t offer sophisticated tools for stock trading, such as leverage

- Product: we couldn’t work freely on user engagement and retention

- Technical: we built an architecture that didn’t align with industry standards

All this was because we were working in a regulated area and lacked deep domain expertise, that is, we didn’t have experienced people on the team who had already solved similar problems in this industry before.

GP: Let’s discuss those one by one. What were the legal issues and how have they influenced your work?

Brokerage, that is, buying and selling shares, is a licensed activity. Holding purchased shares also requires a license to act as a custodian depository. Revolut had neither of those.

One of the ways to start Revolut Trading was to get a license ourselves. This is an exhaustive process that requires time, paperwork, and a deep understanding of how the business will work.

To avoid wasting time, we decided to use an alternative method and find a company that would rent us a license. In addition to the license itself, such a company has the right to regulatory oversight. Simply put, they verify that our AML (anti-money laundering) and KYC procedures are in compliance with the regulator’s requirements, and they are responsible for the quality of verification with their license. These companies are known as “umbrellas” (because they cover you like an umbrella).

The services of these companies are expensive, but they can speed up the process. With their help, you can build all the necessary processes within the company without hiring your own compliance officer.

But it was not enough for us to conclude a contract with an umbrella company, a company that would allow us to trade shares of American, British and European companies. We also needed a place to store the shares—a custodian. This is also necessary in order to comply with the requirements of the regulator. According to law, it is the custodian who is responsible for ensuring that the money for the sold shares reaches the client.

So we came up with a three-party scheme: Revolut Trading, an umbrella company, and a custodian. I must say right away that such a contract was a very non-standard decision. This happened because we wanted to significantly reduce the cost of trading for end users, and we were looking for various unobvious ways to negotiate with partners – market participants. But it turned out that no one except us was interested in changing their work models. This complex scheme of three partners was coordinated for two to three months, with lawyers of each party meeting numerous times.

In the end, we still managed to agree—all the participants were interested in this partnership. But a week before signing the contract, one of the parties refused to sign the documents, as their lawyers said that such a contract is impossible from a legal perspective.

We had to look for new partners and rebuild the whole scheme again. It took several more months, during which we couldn’t work on the Revolut Trading product.

GP: So you thought you would save time, but ended up spending even more time inventing an unobvious solution that didn’t work in the end?

Right. But then we launched with another partner, American B2B broker DriveWealth, which covered both trading and holding shares. But they could only work with shares of American companies, so we had to forgo entering the European and British stock markets. But the signing of the contract and integration went pretty quickly.

When I left Revolut, this plan was still working, although the documents for obtaining our own license, as far as I know, were already ready.

GP: What was wrong with this plan? Why did you decide to get the documents for your own license?

First, it later turned out that getting a license for a small company was easier than we initially thought. It was enough to explain to the regulator exactly how we were planning to work, at the level of developments and proof of concept. The regulator will approve the design if he can confirm that future customers will not be harmed from the company’s actions.

Second, the license would untie our hands: it would allow us to add more functions to the service, independently determine the “risk appetite” (the level of risk that the company is ready to take upon itself—in conjunction with the umbrella it is quite conservative), engage in advertising without requiring approval from the license holder, sell ETFs, and provide ISA which are accounts with tax benefits.

GP: Was there no one on the team who could have foreseen these problems?

We had one interesting example. During the interviews, we asked candidates to come up with a legal scheme and plan to launch Revolut Trading product. As a result, 20 people sent 20 different solutions, although each of them already had ten years of experience. Before, we thought that our options were limited, but after seeing the plans, we realized there were a lot of different ways we could tackle the problem.

The difference in their approaches was mainly due to different previous experiences: some had worked on the custodian side, some in the front office. But among them there was no person who assembled a similar setup from scratch before, except for one person, Andre Mohamed, who became our Head of Wealth and Trading. He immediately warned us that the plan to enter three-party contracts would not work. But at that time, we had already decided on the scheme and didn’t listen to him. Consequently, we had to rebuild the model.

In any case, all applicants had prior knowledge, and they based their solutions on their experience, and all of us could discuss this topic. As a rule, in the field of regulation, there are no right and wrong answers. There are different solutions. Depending on the flexibility of the mind and openness to new things, you can try to agree on how to find unobvious but working solutions.

In order to create a new type of product and influence the industry, it is very important to find the balance between a conservative approach and new approaches that will affect the status quo. Looking back, I can say that we often went too far in search of novel solutions in places where we shouldn’t have.

GP: Did the lack of a license also affect the marketing and promotion of the product?

Yes, we didn’t have external marketing at all. I will try to explain as briefly as possible why it was like that.

Revolut, as the Appointed Representative and Tied Agent (which expresses the status in relation to the “umbrella” – the license holder) was obliged to approve any advertising materials. At the same time, our partner, as a rule, tried to refuse everything or delayed the approval for one or two months. The partner also obliged us to add clarifications to each of our creatives that this is a high-risk product and, roughly speaking, it is better not to use it.

Such advertising would only scare away newcomers, so during the first year after the launch, we didn’t have any external advertising at all—only information about the launch of the product in the blog. The lengthy approval process also made it impossible to do situational marketing.

Therefore, we could only promote the product inside the Revolut app. Among the promotion mechanisms, we had email and push notifications to the Revolut user base, as well as mentions in the company’s news and social networks. Inside the product, we showed the banner to users who had access to Trading.

If we didn’t have restrictions on the marketing side, then we could have grown much more aggressively and attracted users to the product through advertising. Again, the lack of sufficient regulatory expertise and understanding of the consequences of the chosen legal scheme had a strong impact on the development of the service.

GP: Regulatory restrictions have affected your work at the product level as well. Can you give an example?

Sure. But first, I will need to give a little more context about how the product was used.

According to my analysis, about 10% of new users bought stocks in large quantities and aimed at long-term investments without much activity. And there were those who were regularly gambling with their funds: once a week they bought, sold, bought again, sold again. It is difficult to estimate their share of the trades, but I calculated that they were about 20-30% of users.

But the biggest cohort, who constituted about 40% of users, went through onboarding, made a small investment, and then left. Notably, these were users who already knew how to use the entire functionality of the product: to buy, sell, fund an account. Simply put, these were the most experienced users. It was most interesting to work with users who became inactive, because they responded well to various changes in the product.

We placed the survey and found out that this happened due to the fact that they came, saw a list of stocks—and in general they were interested in the product and the market—but they had absolutely no idea about which stock to buy. Several companies like Apple or Tesla were familiar to them, but the others were not, despite the fact that there was a list of hundreds of the most popular companies.

The most obvious solution would be to provide personalized recommendations to our users. But, as you might have already guessed, it was impossible to do this.

GP: Why couldn’t you make a recommendation?

Due to restrictions on the part of the regulator, one cannot give individual advice without a special license. You’re only allowed to give objective information, i.e., indisputable facts.

Therefore, we had a hypothesis that if the app showed more information about the listed companies, various news, charts, indices, etc., it would help people to better understand which stocks were worth buying.

Most products do this, but it is pointless to copy them unless you understand why this is necessary from your own experience. After we added all these things, the inactive cohort began to shrink—and this served as a confirmation that we made the right choice.

Another discovery was that external triggers are the most important factor in buying and selling activities. For example, this trigger can be some big news about the companies listed in the app. Regardless of the features inside the app, as soon as such news surfaced, the behavior of users changes dramatically, and they run to make trades.

It turns out that in order for users to come more often, you must provide them with as much news as possible in the most convenient way to give them a good picture of what is happening on the market.

GP: You mentioned that the Robinhood business model failed to work in Europe. What did you make money on then?

Unlike Robinhood, which only provides trading services (and accordingly only makes money from trading fees), Revolut offers a line of financial products, including insurance, currency exchange, and cryptocurrency. Therefore, we could first offer an investment product to existing users as an additional service, and then think about how to monetize it.

As a result, we were earning money on two things.

First, we received a certain share of the subscription fee.

Second, we had paid trades. After users exhausted their free trades (their number depends on the subscription), they pay £1 per trade. Every pound earned in this way could cover the costs of one paid trade and four free trades: the P&L here was all right.

GP: Did you calculate P&L for Revolut Trading separate from Revolut?

Yes. And therefore we were able to detect the discrepancy on time.

And this is how it went: In the beginning, we launched 300 popular stocks such as Tesla and Amazon. At some point, we began to expand this list and add more, up to 1,000 shares.

Some of the stocks happened to be cheap and rarely traded. Under a contract with a partner, we paid a significantly higher commission for such shares than for all others.

For example, if a user buys 100 shares of Apple, we pay the partner a fairly low commission. But if a person buys a rarer share that is low-priced, then the commission could reach 100 pounds. This is where P&L began to diverge.

Consequently, we began to remove such stocks because they were very expensive for us. This is completely normal, since more than 20,000 shares are traded in the world and it is difficult to sell all of them.

Companies often limit the choice of stocks for more prosaic reasons—for each of them you need to draw an icon, pull up some other data—but not all of them are really needed. Even if you put out a list of 2,000 shares, 80% of users will still buy no more than 15 of them.

This sounds like Pareto’s law, but keep in mind that the composition of these fifteen stocks changes slightly over time. Relatively speaking, no one bought GameStop a year ago, but now they do. But facts are facts: thousands of other promotions add nothing but money loss and problems.

GP: Tell us how Robinhood makes money to make it clearer why their model could not be copied or partially borrowed.

I must say right away that I don’t know everything. But Robinhood is a full-fledged broker with its own buy and sell flow, which allows them to provide more ways to trade. For example, leverage (trading with leverage) is essentially the issuance of a loan from which you can get a percentage of earnings. Robinhood also makes money from this by including this type of trading in its subscription.

Another significant way they earn money, or at least cover their expenses, is possible in the United States but is prohibited in the UK. In the United States, they have PFOF (payment for order flow), where a broker fills orders not through the exchange directly but through the so-called market maker, a large player who undertakes to buy and sell large volumes in order to maintain supply and demand.

Let’s say a million Robinhood users want to buy one Apple share each, all at the same time. Then Robinhood turns to its market maker, who conventionally takes them in bulk from the exchange under more favorable terms, and gives them to users with a mark-up of a fraction of a cent. This delta, i.e., the difference, is divided between market maker and Robinhood.

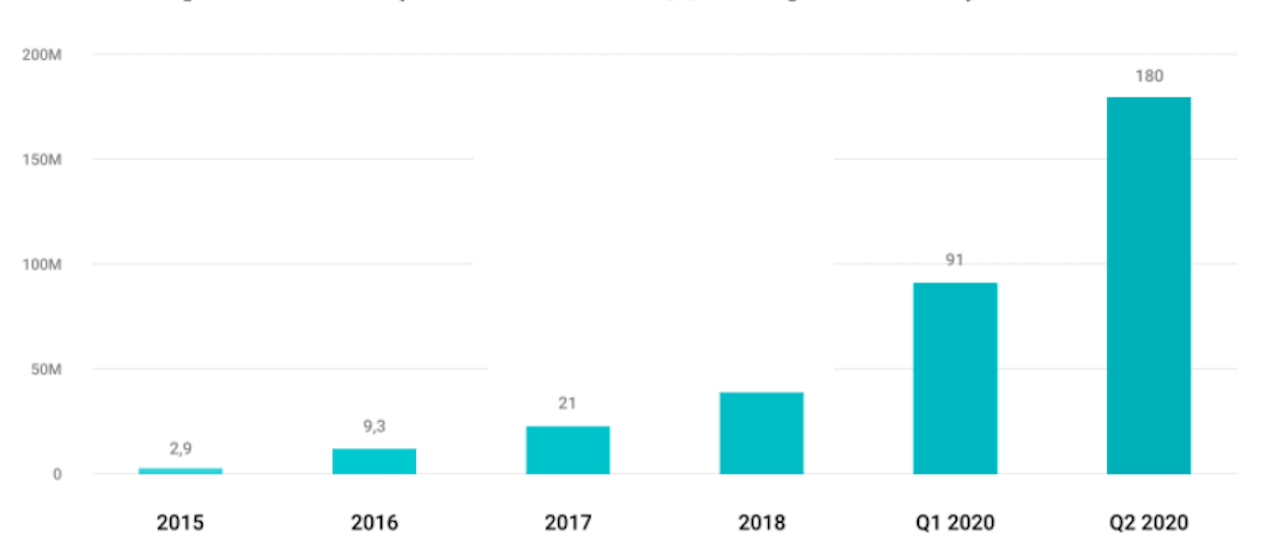

Robinhood Markets Inc. revenue from 2015 till Q2 2020 in million $

GP: What went wrong with the technical architecture of the product?

We did not have a single developer in our company who had previously written code for trading products. At that time, our backend developers were amazing professionals but had no experience in the domain of buying and selling shares.

Early on, we agreed on a generic architecture that was used in both the core Revolut product and Revolut Trading. It turned out to be at odds with industry trading standards. And in the end it cost us dearly.

In banking, we have “transactions.” When you pay for something, the transaction’s status changes, for example, from ‘pending’ to ‘completed’. We decided that we could apply the same architecture (transactions status change) to Trading. We should have one entity with a similar status system: ‘placed’, ‘pending’, ‘completed’. But in the real trading industry, not one but two entities are used: Order and Trade.

For example, a user places an Order to buy 10 Apple shares. This order can be executed in one Trade, in several, or not at all. When Order is executed, at least two entities appear – Order with the ‘filled’ (or ‘partly filled’) status and Trade.

As a result, due to the architecture, which failed to differentiate between Order and Trade, we ran into problems. First, we couldn’t simply generate reports on user actions required by the regulator. In the classic scheme, one could simply send a piece of the table. Second, we could not properly handle cases of partial Order execution or cases where Order was executed in two Trades.

To fix these problems, we had to create some sort of crutches. For example, we could have thought out the need to create tables for reporting to the regulator in advance, worked it out, and saved ourselves two to three weeks of development.

GP: How much time did you waste on this?

Errors and shortcomings accumulated into 6-9 months of work. During this period, everything had to be corrected and rewritten. And the problems with transactions and trades were not the only challenges we faced. For example, trade turned out to be unstable against heavy loads at the beginning of trading.

Such loads can occur in the morning, when people read the news, and at lunchtime in London, when the American stock market opens. At such moments, the hype grows, and in the first five seconds, people tend to buy or sell a lot of shares.

When clicking the Buy button, the user expects to buy the stock in question at the price displayed on the screen at that moment (although the service does not guarantee this). This is especially important when selling stocks. For example, when stocks begin to lose value, the user seeks to sell them as soon as possible. Most likely, there are many users who want to sell at the same time. If orders stop being fulfilled and there is a delay in the system because we did not anticipate the peak load, then many people will be terribly unhappy.

In other words, if the interface is a little unintuitive but it works stably and well, it is better than a perfect user interface supported by an unstable backend. The real work with the user does not take place in the UI, but under the hood.

Reliability is a very important factor in trading, which greatly influences the key metrics. If orders come in and are not fulfilled, then people will struggle once or twice, and then they will probably leave the product. Lack of security kills many products. In trading, stable service is almost as important as security.

Summing it up. If we did it from scratch again

GP: You’ve managed to build a successful product that is a leader in its market segment. But at the same time, there were quite a few things that did not go according to plan. How would you structure your work if you had to start over?

The main thing I would do is to invest time in understanding and gaining knowledge on the industry.

This can be done at several levels:

- Hire people with experience in this area – with knowledge of the domain and the regulator

- Figure it out on your own as much as possible

- Build processes based on this knowledge in a balanced way. Strive for something new, don’t reinvent the wheel.

GP: Let’s sum it up. Why is it so important to hire people with domain expertise?

At the start, I expected that Trading is just another product we could figure out at the top level and then deal only with the product part. It turned out that I was wrong. Maybe we would not have even launched Revolut Trading if Andre Mohamed, a person with a strong expertise in the field, had not joined us at some point.

While working on such a product, it is impossible to bypass the regulator. You can’t just come up with and launch a feature without consulting anyone—a regulator can fine you if this feature breaks the law. To avoid this, you need to understand in detail how the work of existing brokers is arranged. You shouldn’t come up with something of your own on top of generally accepted industry standards if it doesn’t create any added value.

It turned out that it is very important to hire not only talented developers, but also specialists with domain expertise who will help to avoid all of the above mistakes.

At the same time, it is very important to maintain a balance between the industry veterans and those who want to change the market. If this balance is skewed, you can either get a product that is too conservative and has nothing fundamentally new or one that has inventiveness at various levels. The latter leads to schemes that may not work at technical, product, or legal levels.

And, of course, it is important to figure things out for yourself as much as possible.

GP: How do you figure it out yourself? Where to find the necessary knowledge?

At the level of product work, it is useful to start building the product from the most risky parts. This will provide a lot of valuable knowledge.

For example, even before Trading, we were preparing the MVP of another product, and we worked in chronological order, starting with the onboarding, which the designer came up with first. This approach turned out to be ineffective, since we spent a lot of time and effort before we got to the key functionality, without which the product, in principle, does not make sense. Then I had to change a lot.

If we had worked through this most important part at the very beginning, we would have encountered acute problems much earlier and would have made better decisions. Having dealt with the main risks, we would move on to creating auxiliary structures that lead the person to the core value.

In working on Revolut Trading, we took this experience into account and began to build the product around the most important actions: buying and selling shares. In the beginning, we simply built the funtionality which allowed users to buy and sell one specific share. This allowed us to drive out the entire chain of related actions: from how to supply money to a partner to very subtle legal details.

GP: What about the industry knowledge?

When creating a product in a complex regulated area, knowledge of how the market and industry works is perhaps even more important than pure product and growth knowledge and skills.

If I had to start from scratch now, I would take three or four courses on how trading really works. There are a lot of such courses. For example, those who want to work for a broker must take a course and obtain a certificate or a certain license to do so.

I tried to get such information from people from other large companies. I also read articles on the Internet. It wasn’t enough. Knowledge obtained from third parties is all guesswork, nothing but speculation. They are not systematic and don’t help much. The example I gave above, with twenty different solutions from people with expertise, illustrates this problem to some extent.

When Andre Mohamed came to us, he said, “It’s simple. You open the most basic courses, take them, and you already know more than 90% of the people in the company.” Now I would definitely spend less time on conversations and more on learning in order to gain knowledge that can be systematically put together.

It’s like the parable of the elephant and the blind men, where each one touches different parts of the elephant, and as a result, describes it differently—it is impossible to paint a complete picture.