Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) is a well-known theory that examines products through the lens of the work customers “hire” them to do.

The concept has led to numerous interpretations, some of which evolved into complete frameworks.

In this article, we will examine the primary interpretations of JTBD and the frameworks built on them: Clayton Christensen’s original theory, Bob Moesta’s Demand-Side Sales framework, and Tony Ulwick’s Outcome-Driven Innovation.

We will also explore their differences and assess their suitability for various products and tasks.

The origins of different JTBD versions

“People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!”

This quote by the renowned American economist and Harvard Business School professor Theodore Levitt captures the idea that people need results, not products.

The JTBD theory follows the same logic. The theory was first popularized by American scholar, Harvard Business School professor, and business consultant Clayton Christensen in his book The innovator’s solution. Creating and sustaining successful growth. The term “Jobs to Be Done,” however, came into common use later.

In essence, the JTBD concept suggests that people “hire” products and services to complete certain “jobs” in their lives. Therefore, understanding these “jobs” is the most critical aspect of creating in-demand products.

While Christensen popularized the concept, business consultant Tony Ulwick played a key role in shaping it. In 1999, Ulwick shared his Outcome-Driven Innovation approach and real-world applications with Christensen, who later included these examples in his book.

Another influential figure in JTBD was Bob Moesta, who worked on the JTBD theory under Christensen’s guidance at Harvard Business School and later developed these ideas into his Demand-Side Sales framework.

The variety of approaches (with Christensen, Ulwick, and Moesta being the primary but not sole JTBD proponents) has caused a problem: there are too many interpretations of JTBD. These approaches use common terms but apply distinct emphases and definitions.

To help you navigate these frameworks, we’ll break down each approach, highlight key differences, and provide clear guidance on which framework works best for specific products and stages of development.

We will address these questions:

- What is the original JTBD theory really about?

- What is Bob Moesta’s Demand-Side Sales?

- What is Tony Ulwick’s Outcome-Driven Innovation?

- How, when, and for whom should these frameworks be applied?

Now, a brief comparison.

JTBD interpretations: a quick comparison

Important Note

In most publications, Christensen’s foundational work on JTBD is often referred to as a “theory” (Christensen himself calls it “Jobs Theory”), while Ulwick’s and Moesta’s works are considered as methodology or framework.

Indeed, Outcome-Driven Innovation and Demand-Side Sales are more practical approaches that offer specific steps and actions to achieve results.

Christensen’s works provide a conceptual description of the JTBD approach instead of a step-by-step methodology. Christensen’s JTBD is primarily a mindset or lens through which he suggests viewing customers and their needs to create the most relevant and effective products.

But Christensen argues that theoretical insights can be just as valuable as structured methodologies:

“While many in the business world associate the word “theory” with something purely academic or abstract, nothing could be further from the truth. Theories that explain causality are among the most important and practical tools business leaders can have.

Clayton Christensen, Competing Against Luck

Therefore, to avoid confusion and repetition, we will use the terms “theory,” “concept,” “methodology,” and “framework” interchangeably.

While there are other frameworks around the JTBD theory, we will focus on the three ones mentioned above as we deem them the most influential.

Now, let’s briefly compare Christensen’s approach with other frameworks—a more detailed analysis of each will follow.

Clayton Christensen’s Jobs to Be Done theory: overview

People hire products to perform specific jobs in their lives.

A job is an action or set of actions that enables a person to achieve progress in a given context. The need for a job is driven by motivation—factors that prompt a person to make progress.

Focusing on a person’s motivation and context, rather than product features or customer demographics, helps create successful products.

Christensen’s theory is more strategic and less practical compared to other frameworks.

Best fit for

Christensen’s framework is relevant for B2C and B2B products and for large-scale and smaller products.

At its core, Christensen’s Jobs to Be Done urges product creators to invest time in thoroughly researching the specific job their customer wants to accomplish and to help them achieve it more effectively.

Bob Moesta’s Demand-Side Sales: overview

People don’t need to be convinced to buy a product. Demand for a product arises when a combination of factors and life circumstances lead someone to seek a solution to a problem. The key is to show them that a specific product can perform the job better than their current solution. By empathizing with customers’ true motivations and experiences, companies can demonstrate how their products most effectively solve the problems people face.

The Demand-Side Sales framework is very practical and focuses on sales and marketing applications. It encourages research on aspects of the product that will resonate most strongly with customers.

Best fit for

This framework is especially suitable for sales-driven products where a deep understanding of customer motivations and emotional context aids in shaping the marketing and sales strategy.

It is also applicable to companies that develop products iteratively, prioritizing user needs and feedback.

Outcome-Driven Innovation by Tony Ulwick: overview

Each job consists of multiple intermediate desired outcomes. Together, these outcomes determine how effectively the product accomplishes the job. However, no product can perfectly accomplish the job for everyone, as different people prioritize different outcomes.

Therefore, creating an effective product requires identifying a specific audience segment who are not fully satisfied with existing solutions. The foundation of Outcome-Driven Innovation (ODI) is to find this segment, understand their pain points, and demonstrate the value of a more effective solution.

Ulwick’s framework is more structured than others and provides concrete actions for creating in-demand products.

Best fit for

This framework is most suitable for large companies with extensive product lines and the resources to conduct market research. The ODI framework’s focus on quantitative analysis and a structured approach to product innovation makes it ideal for data-driven businesses.

***

We will now explore each approach in depth.

Christensen’s JTBD theory

About the Author

Clayton Christensen, an American scholar, Harvard Business School professor, and business consultant, is well-known in the product community as the author of the disruptive innovation theory—one of the most influential business ideas of the 21st century—and as a prominent advocate of the Jobs to Be Done framework.

Core concepts of Christensen’s approach

Let’s walk through the JTBD concept step-by-step, beginning with its definition.

Defining Jobs to Be Done

Jobs to Be Done (JTBD) is an approach that helps uncover the true reason people use a product. In other words, it identifies the “job” people “hire” a product to accomplish.

What is a job?

A “job” is the progress a person wants to achieve under specific circumstances. It isn’t a single action but a process that brings the person closer to their goal.

What is progress?

In JTBD, progress represents a change in the person’s life. It includes not only completing the task (“I did X”) but also the emotional outcome (“I feel proud of doing X”) and social elements (“I want my family’s approval for doing X”).

The role of context

Jobs arise at the intersection of existing needs in people’s lives and specific circumstances in which these needs emerge (context). Understanding the context is key to uncovering why someone undertakes a particular job.

Example

Say, a person wants to buy a house. This statement is not very informative until we understand the context behind this decision.

What motivated them to buy a house? What events led up to this decision? At what life stage are they? What is their financial status? And so on.

Understanding the context provides a deeper insight into both the motivation and desired progress the person seeks to achieve. Maybe they are looking at the house as an investment—having saved enough money, they want to earn passive income with minimal effort. Or maybe they need more space to accommodate their growing family. In each scenario, different aspects will be critical for the buyer.

JTBD teaches to “dig” beneath people’s actions to discover their true motivation. The primary tool for this is the JTBD interview—customer interviews designed to discover the real reasons behind product use.

How to define the boundaries of a job

Christensen also distinguishes between jobs and needs.

Needs are fairly universal and don’t take into account the person’s context. For example, the need to satisfy hunger varies by context and requires different solutions: a quick snack before a meeting is very different from a post-workout protein shake to aid muscle growth. Hence, a statement like “a person wants to satisfy hunger” doesn’t help much in creating products that meet this need.

Jobs can be achieved in various ways, so an overly specific job formulation like “I want to buy 200 grams of Brand X butter at a Store Y” is also not useful. When defining a job, it’s important to strike the right level of abstraction and granularity: think neither in terms of needs nor as a set of very specific attributes.

Checklist for defining a job

1. It isn’t a trend.

2. It isn’t a high-level need.

3. It isn’t a specific way of solving a task using one product class.

4. It doesn’t imply a single way of solving the task.

5. It includes a task the person wants to accomplish or progress they want to make in life.

6. It includes the context in which the task arises. Different tasks have different contexts, comprising both external factors and internal emotional drivers.

7. It’s defined at a level of abstraction that sets boundaries but still allows room for finding a solution.

What influences the choice of a product to solve a JTBD

How does someone decide which product to hire for a job?

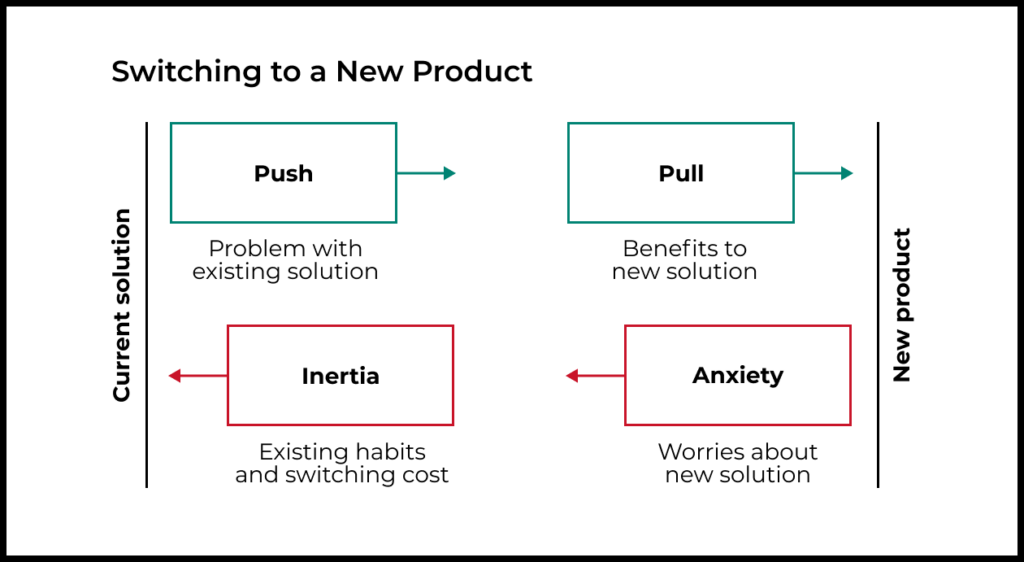

They probably have a solution already. But they might learn about a new approach that can complete the job more effectively. At this point, “four forces” come into play, which Christensen describes in Competing Against Luck:

1. First (F1), the person feels limitations or frustrations with their current solution and becomes open to alternatives.

2. Second (F2), after seeing a new product, they become interested and desire to try it.

3. Third (F3), they need to overcome the anxiety of learning something new.

4. Fourth (F4), they need to leave the comfort zone of their current solution.

In Competing Against Luck, Christensen illustrates how these forces work through his personal experience: For a long time, he resisted changing his mobile phone because the F3 and F4 forces (anxiety of learning something new and the comfort of the current solution) were stronger.

How to apply the original Jobs to Be Done Theory

Above, we covered the main aspects of the original JTBD theory. For a more complete description with many real-world examples, we recommend Competing Against Luck.

Here are the key points on applying JTBD in product management:

– Conduct JTBD interviews: Use these interviews to understand the user’s job and context.

– Prioritize backlog tasks: Organize your backlog based on insights from JTBD interviews to ensure you focus on the most relevant jobs.

– Leverage user job insights for product positioning: Leverage the understanding of user jobs to position your product in a way that effectively communicates the value to the target audience.

Demand-Side Sales by Bob Moesta

About the author

Bob Moesta, one of the co-creators of the original Jobs to Be Done theory, worked alongside Clayton Christensen at Harvard Business School. In the early stages of the theory’s development, Moesta helped Christensen enhance it with real-world case studies.

Later, Moesta founded the consulting firm The Re-Wired Group. Continuing to build on the original JTBD ideas, he developed his own framework for applying the concept in real-world business for marketing and sales—Demand-Side Sales. This framework became the foundation of Moesta’s 2020 book, Demand-Side Sales 101.

Key aspects of the approach

Moesta builds on Christensen’s initial ideas. His Demand-Side Sales framework aligns closely with the original JTBD theory, with some concepts further refined. We won’t repeat definitions from the previous section and will focus on the distinct features.

Focus of Demand-Side Sales

Customers should be viewed through the lens of empathy.

The current context and the desired future state define the progress the customer seeks. Without understanding a person’s context, it’s difficult to sell them a product.

This perspective shifts the focus from the supply side (“What should I do to get my product sold?”) to the demand side (“What are people trying to achieve that my product can help with?”). Hence the name, Demand-Side Sales.

Understanding why a customer wants to get a job done

The best way to learn why someone wants to complete a job is to interview them. The focus should not be on the product but on the state and circumstances that led the customer to “hire” a specific product.

Moesta explains more about conducting these interviews in this YouTube video.

One technique for discovering a customer’s true motivation is the “Five Whys.” Here’s how it works:

- Customer: “I need a drill because I need to make a hole.”

- You: “Why do you need to make a hole?”

- Customer: “I need a hole because I want a plug.”

- You: “Why do you want a plug?”

- Customer: “I need a plug because I want a lamp.”

- You: “Why do you want a lamp?”

- Customer: “Because it’s hard to see, and I want to be able to read better.”

In this case, the customer doesn’t need a drill; they need a way to read comfortably in low light. So, perhaps an iPad or Kindle could be the solution they seek?

When working on a product, it’s crucial to empathize with the customer and view the product through their eyes. Adding more features doesn’t always make the product more appealing. In fact, it often increases customer anxiety as they worry about getting lost in a complex product. This can lead to hesitation and, ultimately, avoidance.

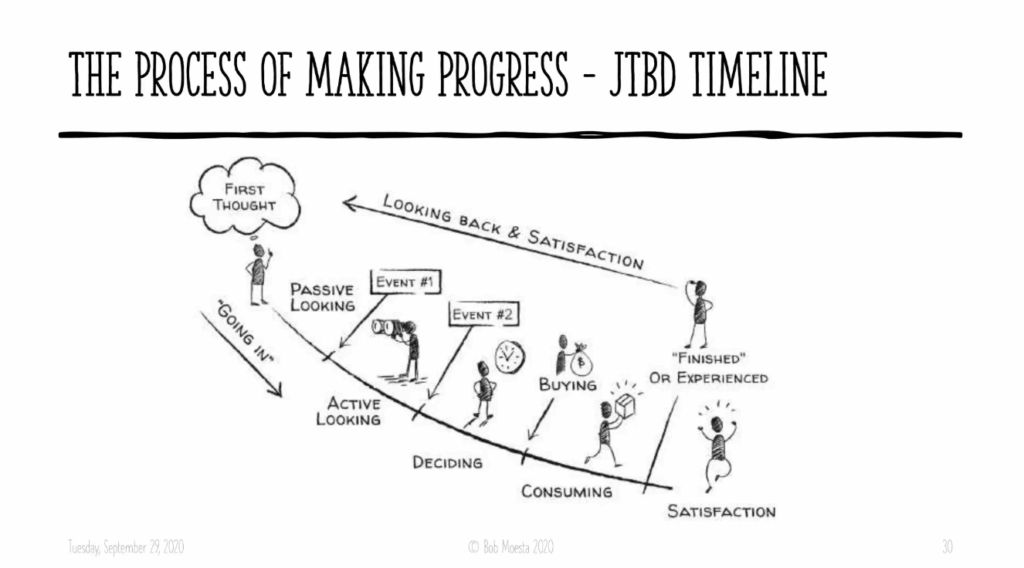

The six steps of the purchasing timeline

Another key component of Moesta’s framework is the six steps of the purchasing timeline.

These steps apply to the purchase of any product, from coffee to cars. The difference is in how much time a person spends moving through each step.

– First thought: The initial thought about the product or switching products. This thought can be triggered by anything. For instance, if someone wants a gaming console, the trigger might be the release of a new game, impressions from friends, or the desire for new entertainment. Without this first thought, demand doesn’t arise.

– Passive looking: Passive exploration of available options. In our example, this could mean browsing the electronics section in a store or talking to a friend who owns a console. The initial thought develops, but the person isn’t yet investing effort into a focused search.

– Active looking: Active research of available options. The need becomes more evident, the person might start looking up reviews, examining features, and comparing models. The outcome of this step is that they rule out options that don’t suit them and shortlist suitable products–not necessarily writing it down but keeping several options in mind.

– Deciding: Making the final decision. This is often the hardest stage. Here, the person realizes that none of the available options are perfect, and every product on the shortlist has tradeoffs. These could be related to price, features, or purchasing requirements. The person prioritizes these factors and discards the least critical ones, which will vary for each individual.

– Onboarding: First experience with the product. The person uses the product for the first time and decides whether it meets expectations. If it doesn’t, they may consider returning it, and in that case, they are unlikely to come back to this product again.

– Ongoing Use: Continued use. If the product passes the initial onboarding, the person starts using it (hiring it for the job) whenever the need arises. It’s at this stage that the person achieves the desired outcome—the state we discussed at the beginning of this section.

More details on the six steps can be found in Moesta’s post.

How to apply Demand-Side Sales

– Conduct JTBD interviews: Interview users to understand why they choose your product and the context that leads them to it.

– Build or refine products based on insights: Use insights from these interviews to build or improve products. Product features should address the jobs users want to complete. Test and iterate on prototypes based on user feedback—does the product help them get the job done more effectively?

– Focus marketing and sales on the job, not features: Align marketing and sales strategies with the specific job the product performs for a particular audience segment, rather than focusing on product features.

– Leverage the six steps of the purchasing timeline: Use the six steps to encourage product purchase. For instance, during the active research phase, create a sense of FOMO by emphasizing limited-time offers. During onboarding, make sure to communicate the product’s value in the shortest possible time to encourage continued use and reduce the likelihood of the user returning to alternative options.

Outcome-Driven Innovation by Tony Ulwick

About the author

Tony Ulwick, founder of the consulting firm Strategyn, is a key figure in developing and popularizing the Jobs to Be Done theory. He independently created the Outcome-Driven Innovation (ODI) framework and presented his findings to Clayton Christensen in 1999. Christensen later built on these ideas, which became known as the JTBD concept. In his 2003 book The Innovator’s Solution, Christensen referenced examples from Ulwick’s practical work at Strategyn.

Ulwick is the author of Jobs to Be Done: Theory to Practice, What Customers Want, and Business Strategy Formulation.

Ulwick describes his Outcome-Driven Innovation framework as follows: “If Jobs to Be Done is the theory, Outcome-Driven Innovation is the practice.”

Key aspects of the approach

Tony Ulwick’s Outcome-Driven Innovation emerged before Clayton Christensen introduced the concept of “jobs” and JTBD theory. Later, as JTBD became widely known, Ulwick positioned ODI as a practical application of JTBD in business.

Per Outcome-Driven Innovation, customers are well aware of their tasks and needs, even if they don’t know the exact solution they need to complete a job. Moreover, they clearly understand which factors are most important for completing the job—such as speed, reliability, or cost. These aspects ultimately define the desired outcomes the customer wants to achieve.

The problem is that most existing products only partially fulfill the job, meaning they cannot meet all the customer’s needs. Therefore, the task for any product creator is to understand customers’ desires and deliver the most effective solution tailored specifically for them.

Ulwick’s Outcome-Driven Innovation includes six steps essential for identifying opportunities and creating the most effective solutions for customers.

Six steps to creating effective products, or how to apply Outcome-Driven Innovation

Below is a summary of each of the six steps outlined by Tony Ulwick. You can find a more detailed description in Ulwick’s article.

1. Define the market and job

The job could be a goal, a task, a problem to be solved, or something people want to avoid.

Markets should not be defined around quickly changing elements like technology but rather around jobs that will be relevant to people over decades.

2. Identify customer needs

Each core job-to-be-done (meaning the job in its most broad description) that a person wants to complete has “desired outcomes,” factors that determine its effectiveness. These outcomes are measurable and can be optimized to improve the overall job performance.

For example, someone who wants to listen to music may care about “minimizing time spent creating a playlist in the correct order” or “minimizing sound distortion at high volume.” These desired outcomes affect the quality of the core job-to-be-done “listening to music.”

Qualitative research, such as individual or group interviews and observations, helps uncover these desired outcomes.

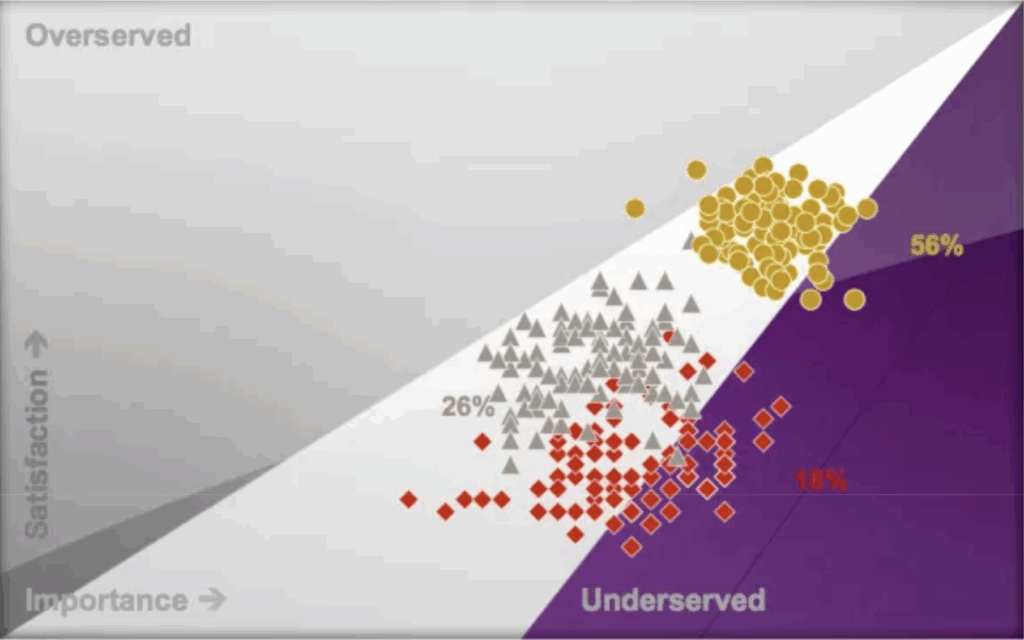

3. Assess how well current needs are met

After identifying the full range of desired outcomes around the core job, use quantitative research (surveys) to evaluate how well each need is met in the market. Customers should rate how well existing products fulfill their desired outcomes.

This assessment can help determine:

- How well customer needs are generally met in the market: which needs are underserved, and which are overserved.

- Opportunities to serve some customers more effectively (for underserved segments).

- Opportunities to serve some customers at a lower cost (for overserved segments).

- Strengths and weaknesses of existing market solutions.

4. Find hidden opportunities

Customers might have different priorities in the same market. For instance, some fast-food customers find the prices too high, others think the food is too greasy, and others are dissatisfied with portion sizes.

This diversity provides opportunities to create more effective solutions. It’s essential to find customer segments with unique unmet needs, but these segments cannot be identified by demographic or geographic characteristics; they require specialized research.

The segmentation process is as follows:

– Identify key variables: Conduct factor analysis on a statistically valid dataset to determine which desired outcomes best explain variance in responses, e.g., outcomes that some customers consider important but unmet, while others consider unimportant but fulfilled.

– Create clusters (segments): Use cluster analysis to segment the market into groups of customers with unique sets of unmet desired outcomes. These unmet outcomes become the basis for segmentation.

– Profile segments: Finally, use profiling questions (included in surveys to understand which variables create complexity) to discover why certain customers have more challenges than others in completing the job. The survey also gathers information on the segment’s size and customers’ willingness to pay more for better job performance.

These insights populate the Opportunity Landscape.

Segmenting customers is crucial, as it determines the product development strategy.

5. Optimize existing products for market opportunities

If a company already has products that could be more effective for certain segments, there are several strategies:

- Communicate specific benefits of products to segments to whom they’re most relevant.

- Launch advertising campaigns around unmet needs.

- Direct leads to solutions that match their needs through a brief questionnaire.

6. Develop new products to address unmet needs

ODI offers several options for this scenario:

- Incorporate relevant features from other products.

- Prioritize essential features in the backlog.

- Partner with other companies to address the needs of identified customer segments.

- Acquire companies or products that meet these needs.

ODI example from Strategyn’s practice:

Using outcome-based segmentation, for example, we were able to discover that about 30% of tradesmen who use circular saws to “cut wood in a straight line” had 14 unmet outcomes, while the remaining population of users didn’t have any unmet outcomes. This hidden segment struggled more than others to get the job done because they encountered complexities that others did not. […] Our outcome-based research methodology revealed the segment, the size of the segment, which needs were underserved, and the degree to which each need was underserved — the key inputs needed to make innovation more predictable. Strategyn’s client created a winning circular saw using this set of inputs.

Summary

The Jobs to Be Done approach is highly effective and has gained a strong following, making it especially valuable for product managers.

Though the original theory developed by Clayton Christensen lacks practical steps, it certainly helps acquire the mental framework necessary to understand how people come around finding and choosing certain products in their lives.

Other frameworks built on or enriched by the JTBD theory, notably Demand-Side Sales and Outcome-Driven Innovation, offer more practical approaches to creating products. But as we showed in this article, they vary in the steps they require and the types of products they work best for.

Learn more

— How to design and run JTBD research interviews: guide and templates

— How user segmentation helps PMs improve products

— Qualitative research in product management: the guide

Illustration by Anna Golde for GoPractice