This is part of a series of articles on the basics of product management and building products that people need.

In this article, we discuss the “growth product manager” role, how and when it appeared, and how it differs from the roles of marketing managers and core product managers. We will also examine the main tools that growth product managers use.

As the product manager profession matured, it began to specialize into different areas. We previously discussed that one of these areas is the task that the product accomplishes. In this respect, the product manager of a B2B task tracker and that of a casual mobile game have very different skill sets.

Another dimension of specialization is the type of product work that the product manager focuses on: Does the PM work on creating value or delivering it to users? It is across this line that core PM and growth PM separate.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

↓ All posts of the series:

→ Addressing user pain points vs solving user problems better.

→ Product manager skills: evolution of a PM role and its transformation.

→ Product metrics, growth metrics, and added value metrics.

→ Customer retention levers: task frequency and added value.

→ How to measure the added value of a product.

→ Should a product be 10 times better to achieve product/market fit?

→ Product/market fit can be weak or strong and can change over time.

→ Two types of product work: creating value and delivering value.

→ What is the difference between growth product manager, marketing manager, and core PM.

A Brief History of Growth Hacking

Product management appeared as a distinct role in FMCG companies in 1931. The role responsible for communicating product value to users crystalized into a separate role much later.

Some might say that communicating value has historically been the responsibility of marketing teams. This is not entirely true. Marketing has been historicly focused on communicating value in specific channels, brand building, and explaining the benefits and capabilities of the product to the target audience. Product teams, on the other hand, were tasked with creating the value itself. However, in many companies, there was a grey zone between these teams that no one owned.

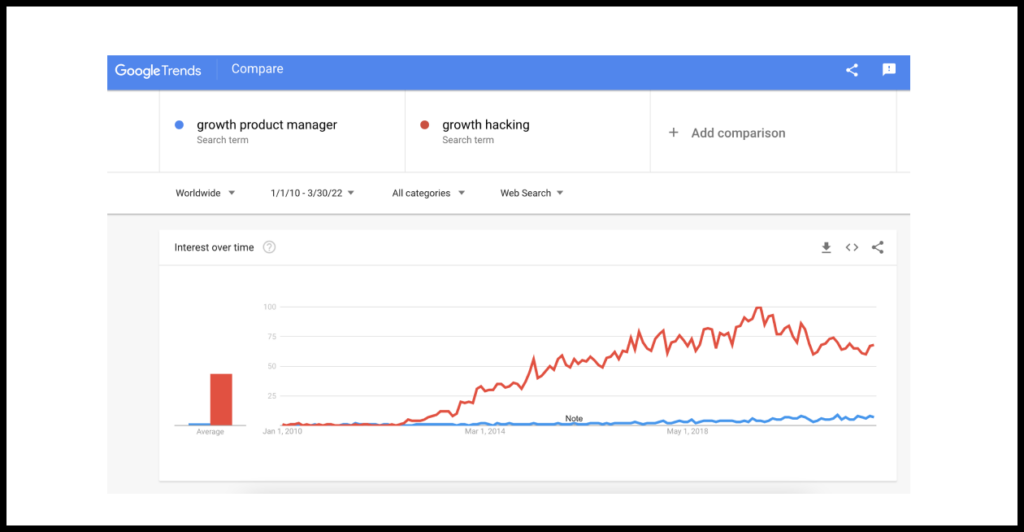

We can assume that the responsibility of conveying the value of the product to users began to form into a separate role as late as 2010 with the advent of the term “Growth Hacking.”

The term Growth Hacking was introduced by Sean Ellis, partner and co-creator of GoPractice educational products. It was then popularized by Andrew Chen in his essay “Growth Hacker is the new VP Marketing”.

Sean was inspired by his experience scaling LogMeIn (acquired at $4.5 billion) and building a growth team at Dropbox (a $10-billion public company).

At these companies, Sean realized that growth work is not limited to marketing, and it goes deep into the product. But at the time, in most companies, product and marketing work were isolated from each other.

As internet connectivity grew, mega platforms appeared, including app stores, online marketplaces, social networks, and search engines. Against this background, companies’ success became increasingly dependent on spotting opportunities to grow and acquire users at the intersection of product work and marketing.

Classical marketers simply didn’t possess the skills required to seize these opportunities, such as working with data, launching product experiments, optimizing funnels, building viral and content growth loops, creating integrations with platforms, and working closely with engineers and designers.

Growth Hacker aggregated all these skills in one role. This person would be responsible for delivering the value of the product to the maximum number of users from the target market. But she would work not only on growth channels (paid channels, media, brand, search) but on the entire funnel, from acquisition to activation and monetization.

It is important to understand that this concept was not fundamentally new. Before Growth Hacking, there were specialists in companies who realized that many levers for growth lie at the intersection of product and marketing (a good example is a Growth team at Facebook). But formally defining this type of work as Growth Hacking made it possible to popularize the concept among wider audience.

Unfortunately, as often happens with something new and popular, Growth Hacking quickly entailed practices that were out of context. Under the guise of working on growth, many “specialists” employed dubious methods focusing on short-term results but creating long-term growth costs for their companies. Looking for cheap “growth hacks,” such specialists inevitably slipped into “dark patterns” – manipulative, dishonest, and—most importantly—unreliable methods of creating the impression of growth. These practices were unrelated to the original idea of Growth Hacking. Eventually, the term “Growth Hacking” began to have increasingly negative connotations over time.

Despite this, the need to solve the original problem didn’t go away. Companies still needed to find ways to leverage new opportunities for delivering value that arose at the junction of platforms, the product, and classic marketing channels. This is where the a new role began to take shape: the growth product manager.

Who is a Growth Product Manager

The growth product manager joins the product team when the team has reached product/market fit, which means it has proven the product’s value for at least one user segment.

The responsibility of the Growth Product Manager is to deliver this value to the maximum number of target users through:

- Choosing the right product form

- Choosing the right monetization model

- Optimizing key funnels

- Working on activation and first session

- Removing friction from key user flows

- Reducing the time between getting acquainted with the product and realizing its value

- Maximizing the potential of the main growth channels.

To better define the boundaries of this role, let’s discuss how it differs from a Core Product Manager and from a Marketing Manager.

Difference between Growth Product Manager and Core Product Manager

The core product manager (aka the classic product manager) focuses on creating added value, that is, a more effective way to solve the problem of target users. On the other hand, the growth product manager finds ways to deliver the product’s value to the maximum number of people who can benefit from it.

Coca-Cola example

Developing the optimal recipe for Coca-Cola is a classic core product job. For example, one of the important aspects of such work may be creating a drink with original taste but without calories (Coca-Cola Zero).

Building systems to deliver the value of such a product is growth work.

For example, different contexts will require different forms of packaging for Coca-Cola Zero: glass bottle, large plastic bottle, and special powder-based mixing system for restaurants and bars.

To launch a new market, the team can tackle the problem of maximizing the proportion of people who have experienced the value of the drink. The tools can be either a classic marketing campaign or organizing promotions where people will be given small cans of Coca-Cola for free.

To increase product availability, the team can provide the owners of small stores with Coca-Cola-branded refrigerators.

Education product example

Now let’s look at an example of an educational product from GoPractice. Early versions of the Simulator comprised a series of Google Docs, regular calls to discuss material, and Q&A sessions with a small group of students. At this stage, the task of the team was to build an educational program that would help students achieve their goals.

When the course reached a point that it was solving people’s problems, work began on packaging this value and finding ways to deliver it to the maximum number of target users—growth work.

At this stage, the team had to answer many questions:

- The form of the educational product: webinars and homework assignments, posting material on a third-party LMS platform or marketplace, internal development of an interactive platform that simulates real work situations with the ability to go through the material at your own pace.

- The product monetization model: One-time payment, subscription with trial, free chapter plus subscription to unlock the remaining chapters, separately sold mini-courses.

- Distribution channels: Paid advertising, search traffic, word of mouth, viral growth loops, community building.

After launch, growth work became even more critical:

- The original mechanisms for buying the Simulator were not suitable for B2B clients. The team had to build additional functionality to sell to companies: group purchases, special registration flows, licenses, the ability to track the progress of a cohort of students.

- The self-paced course wasn’t suitable for all users. One solution would be to create an option where students go through the course with a cohort led by a mentor. This would allow to expand the product/market fit to the adjacent user segment.

Pinterest example

Casey Winters shares an interesting example showing the difference between the two types of product work:

“My first year at Pinterest we built a Maps product and a Q&A product, neither of which had any material impact to the business and were later deleted. In year two, we changed the ‘Pin It’ button to say ‘Save’ and got a 15% increase in activation rate just from that.”

This is an example where the team was able to better explain the essence of the key action to users, just by changing the name of the button. As a result, more users understood what could be done with Pinterest and were able to experience the value of the product.

What is the difference between a Growth Product Manager and a Marketing manager?

The next logical question is, what is the difference between the growth PM and the marketing manager? To find out, let’s look at what levels each of these specialists use for work.

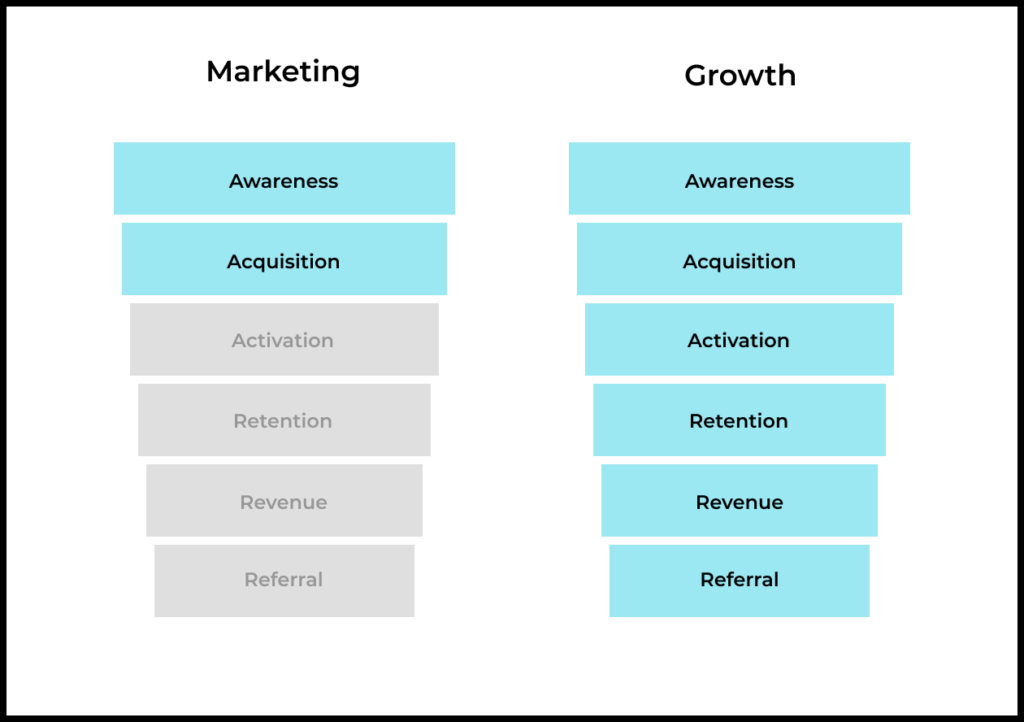

Classical marketing specialists predominantly work at the Awareness and Acquisition levels. They are responsible for specific growth channels (Facebook, Google, organic search, TV ads, influencer or content marketing). They are engaged in building, managing, and optimizing these channels. Key metrics for marketers are the number of new users, leads, downloads, and marketing budget. If the volume of new users from Facebook has stopped growing, then a marketing specialist tweaks campaign settings, budgets, targeting, creatives, and landing pages.

Growth product managers work at all levels of the product’s value delivery funnel. This includes the upper levels (Awareness and Acquisition) and the rest, such as activation, monetization, and viral and referral loops.

Growth product managers can solve problems in the upper levels (channel levels) by making changes at the lower levels. For example, if retention of users coming from Facebook is not reaching a plateau, the problem might be solved by improving product activation or adjusting the level of aggressiveness of the monetization model. If the channel has become saturated, they might switch to building viral or content growth loops.

To work at these levels, you need different skills and team setup than a classical marketing department.

Some might say that good marketers go beyond the top two layers of the funnel. Perhaps they’re right. But in my experience, marketing teams rarely go deep into product territory.

A practical example of differences between growth and marketing approaches to solving a problem

LogMeIn is a remote computer access service valued at $4.3 billion.

Sean Ellis joined the company as VP of Marketing at the very beginning. In the early stages of the company’s development, the main growth channel was paid advertising, in particular paid ads on Google. But Sean had a problem: he could only spend $10,000 per month with a positive return on investment.

For a long time, Sean’s team has been trying to increase the volume of new users by working at the marketing channels level. They tested new channels, creatives, landing pages, but couldn’t break through the impasse.

At some point, Sean and the team decided to go beyond their area of responsibility and look deeper into the product. It turned out that those who experienced the value of the product became regular customers. But only a small part of new users got to the point of using the main features and understanding the added value of the product. The service required complex setup on multiple computers, which few managed to complete.

Realizing the problems in activation, over the following months, the team achieved a significant increase in the proportion of users who successfully installed the product and started using it. The activation rate increased from 5% to 50%.

This significantly increased the strength of the product/market fit. As a result, the retention and effectiveness of the monetization model improved as well. Sean was able to increase his Google AdWords budget by a factor of 50 (up to $1m per month). Even more important was the dramatic increase in the number of users who came through word of mouth—it became the main distribution channel for LogMeIn. A few years later, the company did a successful IPO.

In this example, the team unlocked growth though a specific channel by solving problems at the user activation level. This helped them to improve retention and monetization, which, in turn, made it possible to use paid growth channels more efficiently.

Main tools and focus areas in the work of Growth product managers

We discussed the history of the role of the growth product manager, and how it differs from the role of a marketer or a classic product specialist.

Let’s now discuss the main tools and focus areas of the growth PM:

- User activation: The goal is for as many new users as possible to experience the value of the product, understand that it is better than alternatives, and begin to use it to solve their problems.

- Optimization of key product funnels: Every product has a set of popular paths that users take. Identifying friction along these paths and removing it is another mechanism for improving the delivery of value to users.

- Increasing the use of existing or new features: Features within a product can be viewed as separate products that solve user problems: they may or may not have a product/market fit. The task of the growth product manager is to find users who can benefit from certain features in the product but are not using them yet. The growth PM must then find ways to help these users discover, experience, and continue to receive this value.

- Designing and setting up the monetization model: This is the task of selecting, implementing, and setting up a monetization model that will help deliver the value of the product to the maximum number of users. For some products, a more aggressive monetization model will help deliver value to more people by opening up access to more growth channels. For other products, a softer model opens up more growth opportunities.

- Identifying and developing growth loops at the intersection of product and growth channels: This is the task of building viral, content, and other growth loops to maximize the efficiency of attracting new users.

- Searching for new forms of value delivery: This task can be solved through integration with platforms, placement on marketplaces, as well as other, not quite classical approaches.

In the next series of articles, we will discuss each of these elements in more detail.