Discussions of unit economics sometimes get sidetracked by formulas and business jargon. But you shouldn’t need a special course just to get a handle on this critical concept. Unit economics can actually be easy and even intuitive.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

What unit economics is

Unit economics answers the question “Do you profit from your user (unit)?” So you calculate:

- How much you spent to acquire that user.

- How much you made from that user.

There’s all you truly need to understand unit economics, in just 30 words!

For most online businesses, “user” will be the relevant unit. But other units are possible, too.

For example, Uber might use “ride” as its unit of analysis. In that context, unit economics shows whether or not we (as Uber) make money from a specific ride.

The approach for calculating unit economics remains the same: you calculate how much money you spent to provide that ride, and how much money you made from it.

To keep things simple in our examples here, we will keep “user” as our unit of interest.

Why unit economics matters

When you spend more money to acquire a user than you make from them, it doesn’t make sense to scale your business. You’ll eventually run out of money and your business will fail.

The power of unit economics is in telling you whether the business is ready to grow. Whether a certain sales channel is ripe for scaling. And by how much you need to increase the user’s lifetime value (LTV) or reduce the cost per acquisition (CPA) to get into the positive zone.

When we talk about unit economics being “positive” or “negative”, we are referring to whether you make money from each new user (positive) or lose money (negative).

When in negative territory, you lose money and scaling your business is downright dangerous. (Like in the old joke “We lose money on each sale but make it up on volume.”) But with unit economics that are positive, you’re primed to invest in growth.

How to calculate unit economics

To calculate unit economics, you compare the expenses for acquiring a group of users versus the profit that you obtained from those same users. If you know these numbers, fantastic—you’re practically done already.

Unit economics: the formula

The unit economics formula boils down to comparing two numbers, the LTV and the CPA:

- If LTV > CPA, you have positive unit economics. You make more money from users than you spend on acquiring them.

- If LTV < CPA, your unit economics are negative. The money you make from each user is less than the amount spent to acquire them.

If you don’t have CPA and LTV numbers at hand, here are the steps you’ll need to perform for a given user cohort:

- See how much money you spent acquiring users.

- Divide the expenses by the number of users in that cohort. The result is the cost per acquisition for users in that cohort.

- Calculate gross profit for the user cohort.

- Forecast the future gross profit for that cohort.

- Calculate the LTV for the cohort’s users.

- Compare the LTV and CPA to measure the cohort’s unit economics.

Calculating unit economics, first step: See how much money you spent acquiring users

Identify a user cohort of interest to you and calculate how much money you spent to acquire it.

“Cohort” is just another way of saying “a group of users having one or more things in common”. So any of those could be a cohort:

- Users acquired in March

- Users acquired in March from Facebook ads

- iOS users in Germany acquired in March from Facebook ads

- And so on

By identifying cohorts, you can compare groups of users who came to your product at different times. You can also perform comparative analysis between different acquisition channels, devices, platforms, regions, etc.

Be sure to calculate unit economics separately for different cohorts. That way you can see how the economics vary for different segments. It’s very possible that you have good unit economics for some user segments but not for others. If you lump all users together, you risk missing useful insights.This may also be a good time to refresh your knowledge of cohort analysis.

Calculating unit economics, second step: Divide the expenses by the number of users in that cohort to find the cost of acquiring a single user in the cohort

You’ve just calculated how much money you spent to acquire a certain cohort of users. Now take these expenses and divide them by the number of users in the cohort.

Let’s say that you acquired 1,000 users at a total cost of $500. Then you simply divide $500 by 1,000. The result is 0.5. So the Cost per Acquisition (CPA) for your cohort is fifty cents.

Calculating unit economics, third step: Calculate gross profit for the user cohort

Gross profit refers to how much money you make after the variable costs necessary for obtaining that income (this is also known as COGS, or Cost of Goods Sold).

Your company might use a totally different term, and that’s fine. What’s important is the number, no matter what it happens to be called. We want to know the gross profit: in other words, the profit remaining after subtracting variable expenses.

As a general rule for understanding what qualifies as a variable expense, start by thinking about any expenses that grow proportionately with revenue. A few examples:

- If you sell a mobile app on the App Store, then you should subtract the commission you pay to the store, since you pay this amount for every single sale you make. But you shouldn’t include expenses for your game’s development team. These are fixed expenses that do not directly impact the per-copy cost of your product.

- If you develop and sell complex B2B software, and you have a team of engineers working on product integration specially for a big client, then you should subtract these integration expenses. But you shouldn’t subtract core development expenses related to the software itself, which are fixed R&D expenditures.

- If you sell mittens online, your variable expenses for each transaction will consist of the wholesaler’s price, shipping, payment processing fee, and other related expenses.

You’ve got the idea.

One of the most common mistakes with unit economics is to use revenue instead of gross profit. For some types of businesses, this mistake won’t be critical. For many SaaS businesses, for example, revenue is almost identical to gross profit anyway. But for many other services, this mistake could be incredibly expensive, since their revenue involves much greater expenditures (such as Uber or Dropbox).

Read on here for more on why it’s so important to use profit as the denominator for unit economics.

Calculating unit economics, fourth step: Forecast the future gross profit for that cohort

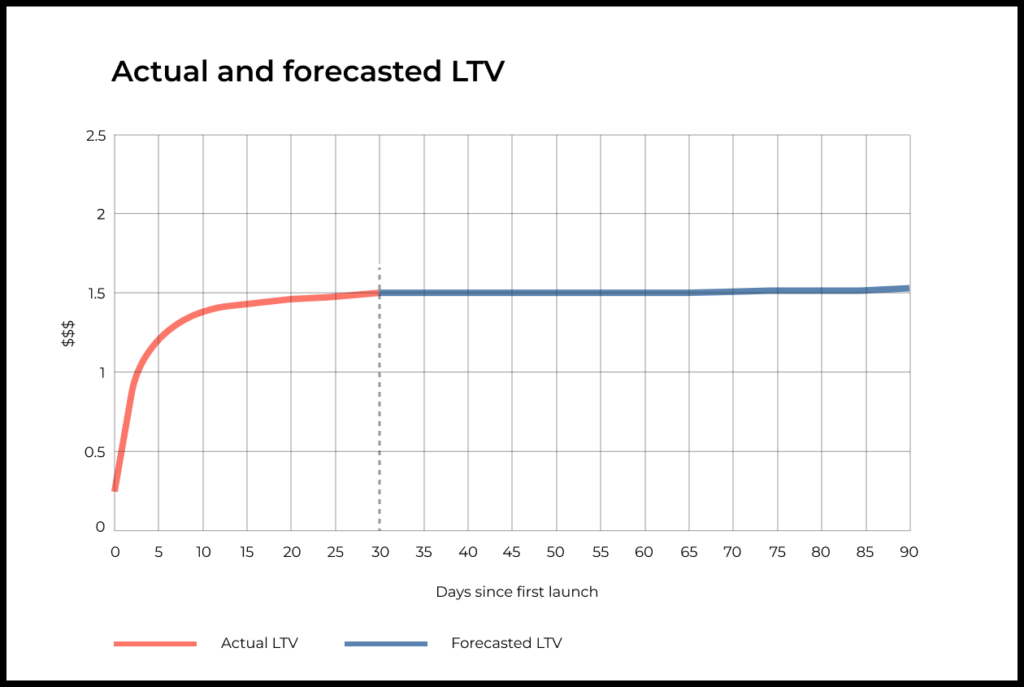

If just a few weeks have gone by since you acquired your user cohort, these users are likely to keep bringing revenue (as well as profit) for a long time yet. So with unit economics, we are less interested in the current ratio of profit to acquisition costs for a cohort than in how this ratio will change over time. To predict gross profit, you can analyze how gross profit changed for other cohorts in the past. Then use this to predict what will happen with your current user cohort.

Read more about cohort analysis and its predictive power here.

Why do I need to forecast future gross profit?

Most of the time, you want to calculate unit economics and make key decisions sooner, without having to wait until Month 5 or Month 12 and see what the actual values are then. Therefore, it’s important to be able to predict gross profit based on just one or two weeks of real data. We are basically talking about a way to predict LTV. This isn’t easy, but it’s doable.

For how many months out should I be forecasting profit?

The answer will depend on your product and situation:

- Companies with venture financing often aim to make back their acquisition outlays within 12–18 months (and sometimes even longer).

- Bootstrapped (self-funded) companies can rarely afford to wait more than 2–6 months to make back acquisition costs.

- For many products, LTV plateaus pretty quickly. That means the flow of cash from acquired clients dries up at a particular point in time. For these cases it’s useful to calculate LTV up to the month when the curve begins to parallel the X axis.

Calculating unit economics, fifth step: Calculate the LTV for the cohort’s users

In the previous steps we’ve calculated the current gross profit from a cohort and forecasted the gross profit from that cohort until moment X after signing up.

Now we divide the expected gross profit as of moment X by the number of users in that cohort.

This gives us the LTV for a new user at time X after sign-up.

Calculating unit economics, sixth step: Compare the CPA and LTV

Take the Cost per Acquisition (CPA) from Step 2 and the gross profit per user at time X (LTV at time Х) from Step 5.

Compare these two numbers to see whether your unit economics are positive.

Congratulations! You’ve got unit economics figured out.

A simple example: applying this method to unit economics for a mobile app

Let’s walk through all those same steps, but with numbers. We’ll be calculating the unit economics for a mobile app within the cohort of users acquired from Facebook ads during a specific month.

We will base unit economics on our forecast for Month 6: this is the payoff period that the app team thinks best fits the business model.

Here is what we know already:

- In January, we acquired 2,500 users from Facebook ads.

- We spent $2,000 to acquire them.

- We know the month-to-month changes in revenue from this group during the January to April period (as seen in the following table).

- Variable expenses equal 15% of revenue each month. So gross profits are 85% of revenue.

May is around the corner as we start crunching the numbers.

Here is the cohort of 2,500 users acquired in January via Facebook ads:

| Month | January | February | March | April |

| Monthly user revenue | $1,000 | $600 | $480 | $440 |

| Variable expenses | $150 | $90 | $72 | $66 |

| Monthly gross profit | $850 | $510 | $408 | $374 |

Step 1

We already know the expenses for acquiring the user cohort: $2,000.

Step 2

We calculate the cost of acquiring each user.

We know that it took $2,000 for us to acquire 2,500 users.

$2000 / 2500 = $0.8

Ergo, the cost per acquisition is eighty cents.

Step 3

We have calculated that cumulative revenue for users in January–May was $2,520. We also know the month-by-month breakdown of when this revenue was booked.

Always use gross profits when calculating unit economics. That’s why we’ve subtracted variable expenses, which happen to equal 15% of revenue each month, from revenue.

So here is the cohort of 2,500 users acquired in January via Facebook advertising:

| Month | January | February | March | April |

| Monthly user revenue | $1,000 | $600 | $480 | $440 |

| Cumulative user revenue (all months) | $1,000 | $1,600 | $2,080 | $2,520 |

| Variable expenses | $150 | $90 | $72 | $66 |

| Monthly gross profit | $850 | $510 | $408 | $374 |

| Cumulative gross profit (all months) | $850 | $1,360 | $1,768 | $2,142 |

Cumulative gross profit for the January–April period totals $2,142.

Step 4

Let’s forecast the profit we’ll make from this cohort up to Month 6. The team assesses that a six-month payback period is well-suited to the business model for this hypothetical product.

Here is the cohort of 2,500 users who were acquired with Facebook ads in January:

| Actual | Actual | Actual | Actual | Forecasted | Forecasted | Forecasted | |

| Month | Jan (0) | Feb (1) | Mar (2) | Apr (3) | May (4) | Jun (5) | Jul (6) |

| Monthly gross profit | $850 | $510 | $408 | $374 | $363 | $360 | $358 |

| Cumulative user revenue (all months) | $850 | $1,360 | $1,768 | $2,142 | $2,505 | $2,865 | $3,223 |

Step 5

Now we’ll calculate the LTV for Month 6 for a user in our cohort. We take the cumulative gross profit for July and divide by the number of acquired users.

$3223 / 2500 = $1.28

Step 6

We compare the Cost per Acquisition (CPA) and LTV at the Month 6 mark:

- CPA is $0.80

- Month 6 LTV is $1.28

LTV > CPA. As of Month 6, the money spent on user acquisition is less than the profit we’re making from that user.

Our unit economics are positive.

But remember, all these calculations were just for one cohort. For all we know, the unit economics could be worse for users who have been acquired via other channels or differ in other important ways. That’s why segmentation is crucial whenever we talk about unit economics.

Even if the unit economics are negative for some of those other cohorts at Month 6, there’s a good chance that they could still turn positive later down the road at Month 12, for example. Perhaps the users from that cohort will have brought enough profit by then to break even.

In that case you still have to ask: Is that right for your business? Are you willing to tough out a payback period lasting 12 months or even longer? Answering that question will take more than just calculating unit economics.

What else to remember about unit economics

Segmenting users is crucial any time you calculate unit economics

We’ve just said it—and it bears saying again. Unit economics can be positive for some acquisition channels while being negative for others. The same applies to any possible way you segment users, whether by country, device, platform, or other characteristics.

Therefore, it is essential that you calculate unit economics individually for each acquisition channel, platform, region, and so on.

Units can represent a new user, paying user, or one who signs up for a trial

The “unit” in the term “unit economics” usually refers to new users. The unit could be a user who has converted to a paying user, or a user who has signed up for a trial. Either way is just fine. Just pick one and stay consistent when calculating the CPA and LTV.

There are some industry conventions you should know, however. For mobile apps and games, “units” tend to refer to new users. In SaaS, though, they’re paying clients. And in e-commerce, a customer who has made a purchase.

Pay attention to the problem of incrementality and attribution models

One of the thorny parts of unit economics is trying to correctly attribute users to specific acquisition channels and the related issue of incrementality.

Attribution is especially challenging for complicated products with a long sales cycle, products with an acquisition funnel spanning multiple devices or browsers, and products with a diverse multichannel marketing mix. This problem also comes up with channels such as TV ads, YouTube, podcasts, and blogger promotions.

If your attribution model is wrong, you’ll be recording acquired users as “organic”. This understates the profits attributable to your ad campaign, potentially causing you to underweight the channel. You could end up getting rid of a channel that is actually bringing in money, or at the very least fail to use that channel to its full potential.

Another very common problem is channel incrementality: even if we hadn’t advertised in a given channel, some of the users from that channel would have come to our product anyway via other mechanisms. Without getting a handle on channel incrementality, you run a high risk of overestimating the channel’s worth, causing you to throw more money on ads that aren’t getting results.

Moreover, channels can impact each other. Channels may simply bring back old users instead of acquiring new ones.

These are all important factors to keep in mind as you calculate unit economics for different channels.

ROI/ROMI vs. unit economics

ROI (Return on Investment) and ROMI (Return on Marketing Investment) are fine metrics that can take the place of, and are closely related to, unit economics. In English-speaking countries, “unit economics” as a term is relatively uncommon. Instead, good old ROI is the coin of the realm.

ROI reflects the return that you will receive on your investment in a given distribution channel. To calculate ROI for a channel, you perform three steps:

- Find the gross profit from clients acquired via this channel.

- Subtract the money spent to get those clients.

- Divide that number by expenses.

ROI = (LTV – CPA) / CPA

Recap

Stay simple and ditch the jargon if you want to truly master unit economics. Overcomplicating things will make it harder to understand what’s happening.

You can get useful practice by unpacking high-level metrics into their components. The best way is to tackle a specific case, not a fuzzy example that attempts to blend every business model simultaneously.

Read and compare:

- We spent $1,000 on advertising campaign X. Users who came thanks to campaign X brought $2,000 in gross profit.

- With advertising campaign X, we acquired 100 users. The cost per acquisition was $10. The conversion rate (of new users to first purchase) was 10%. The average paying user made 3 purchases of $100 each, generating revenue of $300 per paying user. Variable costs for one copy of the product equal $33.3.

We’re saying the same thing in both examples. It is easier to understand what’s going on in the first one, of course. The second one is more complicated but suggests levers that are available to us for nudging the process.

Unit economics should be simple. So don’t make it any more complicated than it has to be.

“It can scarcely be denied that the supreme goal of all theory is to make the irreducible basic elements as simple and as few as possible without having to surrender the adequate representation of a single datum of experience.”

Albert Einstein