Regular use of a product can become a habit. In the previous article we zoomed in on dopamine’s role in this process. This time we will look at a way of thinking about habit formation called the Hook Model, proposed by Nir Eyal.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

The importance of dopamine in habit formation

Let’s recap the role of dopamine in forming habits. It acts as a neurotransmitter, helping the brain to remember behavior patterns that are potentially beneficial for the person and lead to a reward (such as a rush of pleasure hormones after performing a particular action).

Dopamine creates a “loop” that makes us repeat those actions. And when the reward is random or uncertain, dopamine increases even more, which makes the habit even harder to resist. Bigger amounts of dopamine mean a larger chance that the habit will be reinforced.

↓ This is the short series on how people get in the habit of using a particular product, what tools can be used to promote this, why this won’t work for all products, and how to apply this knowledge in practice as part of a product team.

→ How product habits are formed and what dopamine has to do with it.

→ Hook Model: encouraging a product habit to improve retention.

→ Not every product is habit-forming, but all products can have loyal users.

Principles of the Hook Model

Nir Eyal presented the Hook Model in his 2014 book “Hooked: How to Build Habit-Forming Products”. This model reflects how dopamine works in the process of habit formation.

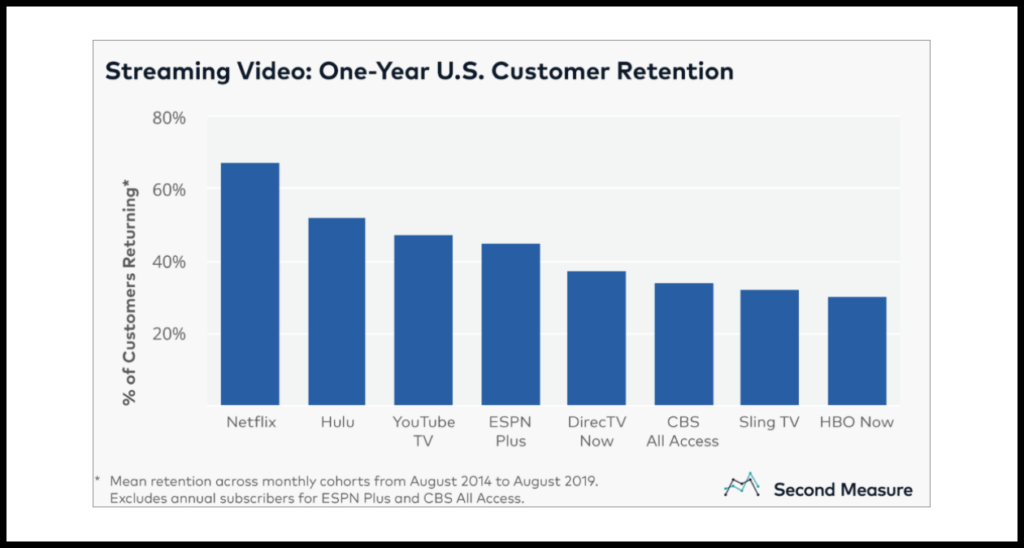

How do businesses benefit from making habit-forming products? A habit obviously improves retention by increasing the frequency at which the user gets the “job” done, and it can also increase the user’s lifetime value (LTV) and pricing flexibility.

How the Hook Model works

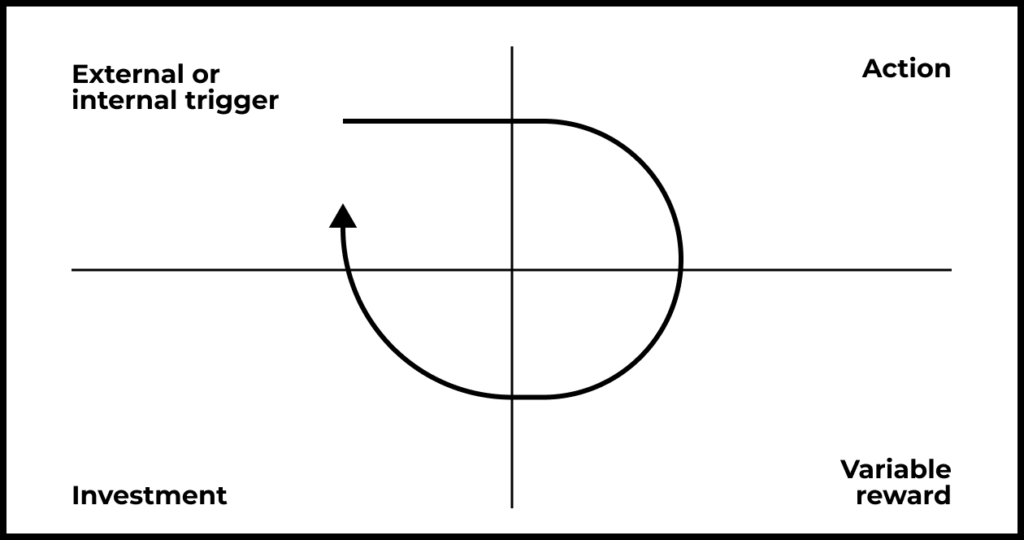

The Hook Model consists of four steps:

- Trigger

- Action

- Variable reward

- Investment

Trigger: The user’s call to action. Triggers come in two types: external and internal. External ones might include push notifications, ads, emails, news stories, or app icons. Examples of internal ones are boredom and loneliness.

Action: What the user does after the trigger, such as publishing a photo or answering a message. At this stage, it’s important to understand the user’s motivation and capacity to perform the action. Performing the action should be as simple and straightforward as possible.

Variable reward: What the user gets in return for that action. Variable rewards are unpredictable, which leads to release of more dopamine.

In a mobile game, the reward could be different bonuses or satisfaction with progressing in the game. In entertainment, the reward could be a funny video. For a social network, a like or a message from someone else. The main thing is that both the timing and the type of the reward be as variable and unpredictable as possible.

The Hook Model includes three types of rewards:

- Reward of the hunt: Valuable information or a great deal within an app

- Reward of the self: Confirmation of mastery at a skill, such as a player defeating ever-stronger bosses and leveling up

- Reward of the tribe: Social approval in the form of likes, comments, and reposts

Investment: After the user receives a reward, the product asks them to do “work” (fill in their profile, indicate their interests, learn new features, invite friends). Investment is aimed at improving the user’s future experience and boosting the odds that they’ll return to the product.

Thanks to the user’s actions at the Investment stage, the product becomes increasingly valuable to them over time. For example, the user’s contact list grows, they progress in a game or upgrade their character in it, or they accumulate playlists with favorite songs and movies.

“These commitments can be leveraged to make the trigger more engaging, the action easier, and the reward more exciting with every pass through the hook cycle.”

Nir Eyal

For a habit to take root, the user needs to pass through this cycle many times so positive experience can reinforce the association between action and satisfaction. The result is an internal trigger acting as a stimulus to return to the app. Internal user triggers are a sure sign of a habit.

Examples of habit-forming products

Let’s try on the Hook Model for size as we break down popular and successful products in terms of Trigger, Action, Reward, and Investment.

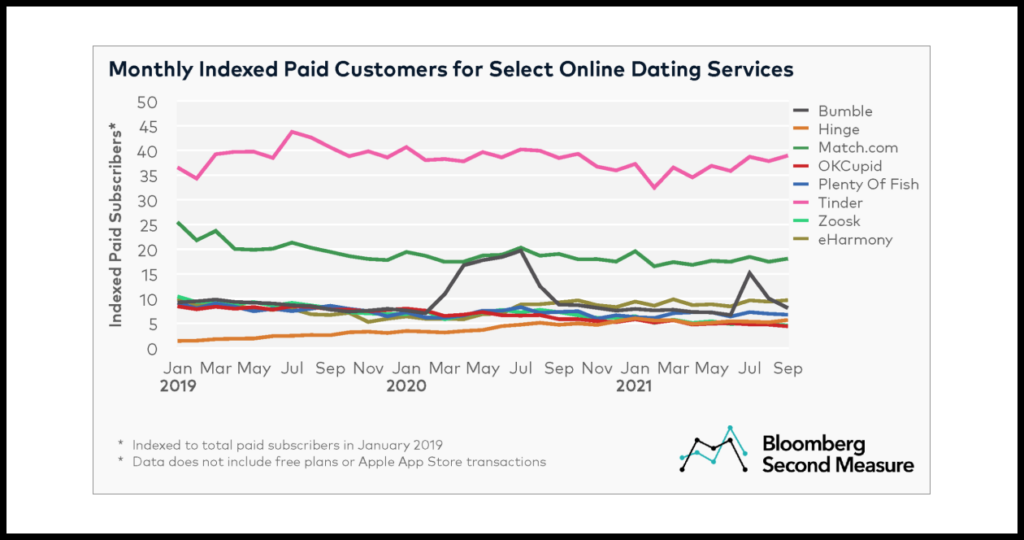

Tinder

User scenarios for Tinder, launched back in 2012, are an excellent illustration of the Hook Model in practice.

The product’s most common use case is to find someone for a date. Tinder uses mechanics that push the user to regularly come back to the app, even if no particular session actually accomplishes the job of “find a date”. Here is how the habit is formed:

Trigger: App icon, message from another user, match notification (external); boredom, feeling of loneliness (internal).

Action: Viewing and swiping other users’ profiles, sending messages.

Reward: “Someone likes me!” (matches and superlikes), “Someone wrote to me!”, “I’m interesting to another person!” (messages).

Investment: Create an original profile with interesting and attractive photos.

In the context of a dating app, investment primarily means optimizing one’s profile to get better results: both in quantity (how many matches and likes) and quality (appeal of the profiles they see). An incidental but very important result of this investment is the user’s list of contacts and matches. If the user deletes their profile, they will lose all this information.

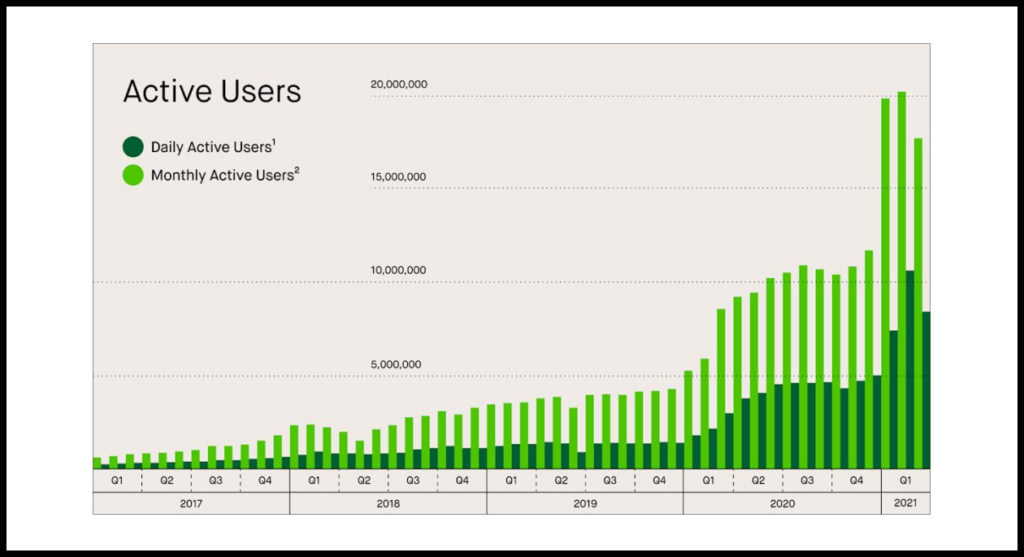

Robinhood

Robinhood is an online brokerage offering commission-free stock trades. Created in 2013, the product truly caught on after the start of the pandemic in 2020. New behavior patterns from investors were a major contributor. During the peak of ”shoot the moon” action in early 2021 with r/WallStreetBets and GameStop shares, Robinhood became a major market intermediary.

The app owes its popularity to zero commissions, gamified investing, and a simple interface compared to products from classic brokers. Learn more about Robinhood and its ilk in the GoPractice interview with Dmitry Vasin from Revolut Trading.

Now apply the Hook Model to Robinhood:

Trigger: Rise or fall in share prices, news about relevant companies, push notifications about changes in portfolio or specific holdings.

Action: Buy or sell shares.

Reward: Emotions from buying or selling shares and booking a profit or loss.

Investment: Create your own portfolio, pay for premium membership.

This loop is then repeated, but the specific triggers and actions might change over time.

It’s easy for a user to experience fear of missing out (FOMO) when they see a company’s share price rising. They rush into the app to buy shares, which brings pleasure and restarts the loop, since now it’s even more interesting to track the share price. Gamifying trading and making the stock market seem fun and welcoming are two complaints heard about Robinhood from critics, who claim that some users have developed a gambling addiction.

Robinhood rejects these criticisms, as well as the claim that the Hook Model inspired the app’s design. That said, in 2012 Robinhood’s future founder Baiju Bhatt met with Nir Eyal. Bloomberg has an interesting read on the topic.

Netflix

Think about how a Netflix habit is formed in terms of the Hook Model:

Trigger: News of a new release, recommendations from friends, app notifications, gnawing boredom.

Action: Watching a movie/show.

Reward: Emotions from watching that movie/show.

Investment: Leave a rating, recommend to a friend, post a review on social media. Investment improves recommendations for the user by training the algorithm to deliver more personalized recommendations.

The recommendation algorithm also helps to reinforce the habit and associate the app with dopamine release. If the user is offered relevant content, they are more likely to return and less likely to abandon it. A comedy lover isn’t going to keep using a streaming site that suggests only gloomy dramas and crime shows.

Candy Crush Saga

One of the most successful match-three games. Gameplay is simple: line up three or more of the same item in a row in order to clear it and win points. Complete levels by scoring enough points in a certain number of moves. Difficulty increases by means of various obstacles.

The mechanics of Candy Crush Saga are typical of most casual and hypercasual mobile games.

Here is the loop for a player of Candy Crush Saga:

Trigger: Push notification, desire to kill time, boredom while waiting in line, downtime at work.

Action: Launch the app and finish a level.

Reward: Get reward for completing a level. Advance in the story or on the map.

Investment: Buy in-game currency and boosters to help complete levels.

Casual mobile games are perhaps the truest “proving ground” for the Hook Model. These games do not require much of their users, but can offer constant and diverse rewards.

Habits can be about the context, not the job

Note that in our examples with Tinder and Robinhood, the user’s habit does not attach to the job that the product is meant to accomplish.

The process of looking for a date or monitoring your stock portfolio does not, by itself, create a habit. Any habit is a result of mechanisms built on top of the product’s core value, enabling users to experience that value more often and, in all likelihood, get that job done more effectively.

What these mechanisms look like:

- For Tinder, getting more matches means social validation and romantic interest from others.

- For Robinhood, FOMO and the thrill of stock trading can be important for retaining users.

But for Candy Crush Saga and Netflix, the product’s job—to get quick satisfaction, kill time, or relax—is virtually inseparable from the habit. The habit here is part and parcel of the job itself.

Healthy vs. harmful habits

Clearly, the Hook Model can be used for creating both good and destructive habits. If abused it can create addiction, which robs a user of the ability to say no.

As mentioned in the initial article of this series, we won’t try to draw a bright line between “habit” and “addiction” in the context of digital products.

As for what the author of “Hooked” has to say about using the Hook Model for good, Nir Eyal recommends that product teams examine personal experience to see whether a product creates a dangerous addiction that damages the user’s mental health or wastes their time to no benefit. But he does not give any straightforward method for creating a user habit that does not carry the risk of addiction. Eyal is confident that most product use does not fall under the category of addiction or harmful habit:

“For the vast majority of people, technology is not an addiction. It’s a distraction.”

We will neither criticize nor defend the Hook Model’s impact on the industry or end users. For an opposing take, read product designer Per Axbom’s essay “How Nir Eyal’s habit books are dangerous”.

In 2019, five years after publishing “Hooked”, Eyal came out with “Indistractable”. The book is targeted at a broad audience interested in techniques for regaining control over their attention.

Concluding thoughts on the Hook Model

Teams can decompose the process of forming user habits into steps and apply this knowledge to the product creation process. One example is the Hook Model, which reflects dopamine’s impact on habit formation.

The Hook Model consists of four stages—Trigger, Action, Reward, and Investment—which when repeated will form a habit. The user becomes subconsciously motivated to use the product.

Habits are an excellent driver of user retention and pricing flexibility. But they attach only to products that users have the potential to use regularly and whose use is associated with pleasure, that is, with an emotional reward.

In the third article of this series, we will look more closely at why not all products can be habit-forming and what makes a habit different from loyalty or high switching cost.