User habits can have a big impact on a product’s long-term success. We will kick off our discussion of habits with how people develop them and the ways in which popular products nudge users to keep coming back.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

Habit vs. addiction vs. loyalty

In the product context, it’s easy to blur the differences between habit, addiction, and loyalty. After all, any of these can inspire a user to frequently come back to the product and keep selecting it over the alternatives.

But let’s grapple first with the big question: when is user behavior a “habit” and when is it best called something else?

What a habit is

By habit we refer to an action that a person performs unconsciously (or semi-consciously) on a frequent and ongoing basis. Whenever that person can’t perform the action for whatever reason, they feel discomfort.

Examples of daily habits might include:

- Taking the same route to work every day.

- Putting keys in a particular pocket.

- Looking both ways before crossing the street.

Product-related habits could be:

- Reading newsfeeds and social networks every morning right after waking up.

- Checking in at different locations on social networks or services like Swarm from Foursquare.

We perform these actions without thinking and, if we can’t do them, we feel anxious or upset. Because these actions are so automatic, we free up our brain’s “operating memory” to use for thinking about other things.

It can be hard to draw a line between habit and addiction, especially in the context of digital products like social networks or video games. We would say that the key difference is that with addiction, all of a person’s actions are directed at obtaining the thing in question. All other areas of life suffer as a result.

Where (and whether) to draw the line between habit and addiction is beyond the scope of this article. Finding the answer involves questions of biology and ethics that we cannot address authoritatively here.

What a habit isn’t

Let’s try to draw a line, though, between a habit that a user has and their loyalty to the product.

Remember that a habit is an unconscious or semi-conscious act that is frequent or ongoing. Loyalty, by contrast, is often the result of rational choice and does not necessarily imply high frequency.

Examples:

- Buying appliances of a certain brand.

- Going to the same café again and again.

- Flying on a particular airline.

Loyalty can be the result of several factors:

- The user believes that the product gets the job done better than the alternatives. Uber might be cheaper and faster than a yellow cab, for example.

- High cost of switching. If a user is locked into the Apple ecosystem, it becomes prohibitively difficult to switch to devices from other vendors.

- Top-of-Mind and other factors in brand attractiveness.

↓ This is the short series on how people get in the habit of using a particular product, what tools can be used to promote this, why this won’t work for all products, and how to apply this knowledge in practice as part of a product team.

→ How product habits are formed and what dopamine has to do with it.

→ Hook Model: encouraging a product habit to improve retention.

→ Not every product is habit-forming, but all products can have loyal users.

Dopamine and its role in habit formation

Pleasant experiences shape behavior patterns as a result of dopamine, which is a hormone and neurotransmitter. In other words, dopamine is the “glue” that attaches pleasure to a habit.

We have simplified scientific explanations here in the interest of readability and accessible terminology. The full picture of dopamine’s workings, of course, is rather more complicated and best understood with a background in neurobiology.

One of dopamine’s roles is to reinforce experiences and push us to seek novelty. It has played a major role in human evolution. For more on its impact on behaviors, preferences, and even political views, check out books such as “The Molecule of More” by Daniel Z. Lieberman and Michael E. Long.

From an evolutionary perspective, dopamine helps to increase our likelihood of survival. By releasing dopamine, the brain reinforces behavioral patterns that seem to benefit the body.

Keep in mind that dopamine by itself is not a “pleasure hormone”. Rather, it creates associations with a pleasure-bringing action, motivating us to perform that action again.

Mechanism by which dopamine forms habits

What is the role of dopamine in forming habits?

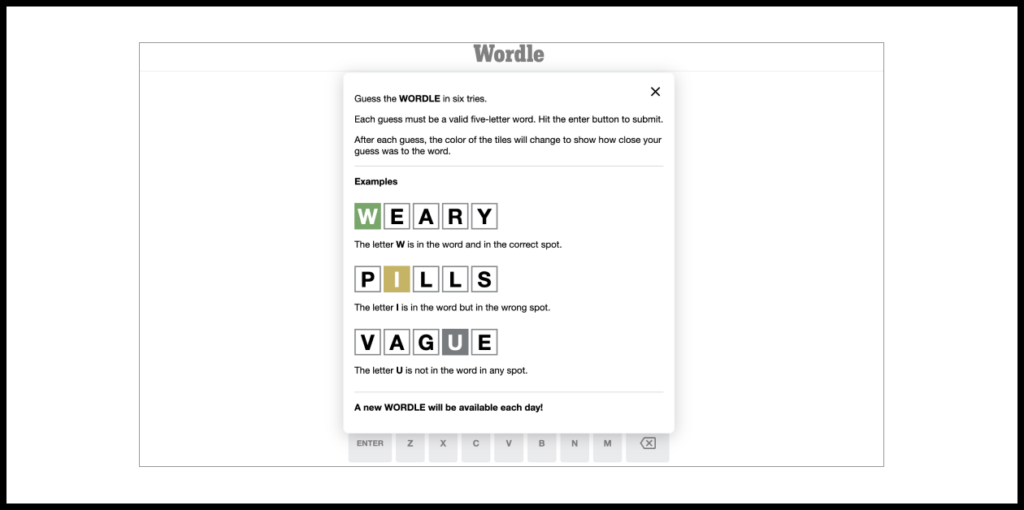

Here’s a basic example. A friend has shown you Wordle, a popular new game. You get six attempts to guess a five-letter word. When you type your guesses, any letters that appear in the mystery word light up.

So you haven’t heard of the game before but decide to give it a try. Down to the wire with no more guesses left, you successfully solve the puzzle and experience pleasure. Your brain now releases a hormone-rich cocktail that includes dopamine.

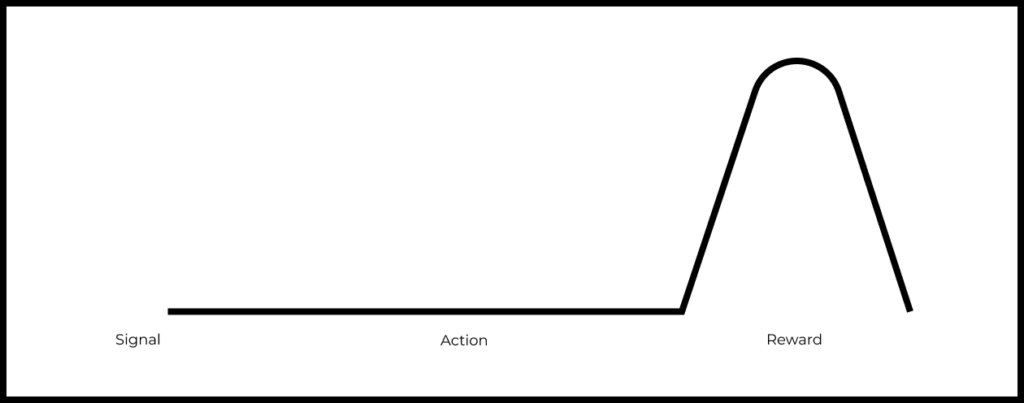

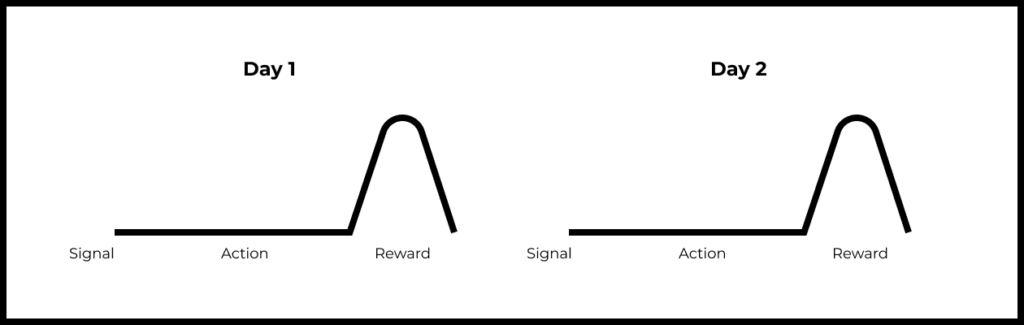

This process can be split into three stages: Signal, Work, and Reward. These are the stages identified by scientists such as American researcher Robert Sapolsky, whose experiments we will detail a bit later. In our Wordle example, the stages would be:

- Invitation to play (Signal)

- Opening the app and completing the level (Work)

- Joy of victory (Reward)

At the moment of victory, you experience pleasure and your brain releases a rush of hormones, including dopamine.

Then you play the game again the next day. This time you do even better and solve the puzzle almost immediately. The signal might be different from last time: maybe you saw someone bragging about their own win on social media or maybe you just remembered your experience from the day before. That same intoxicating cocktail of hormones shoots forth yet again and you feel happy (especially if you did better than your friend!).

The brain remembers that this action is pleasurable. The job of dopamine is to make you want to do it again and again.

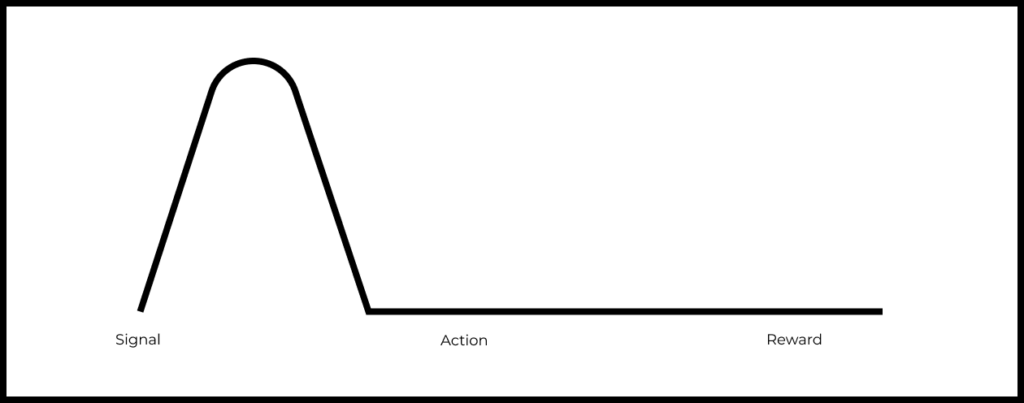

This works because the dopamine rush comes not when you get the reward, but when the signal appears. Now a habit has been formed: when the trigger appears, you want to complete an action.

You then start playing every day and the game becomes a daily habit. This is reinforcement, a critical part of the process of forming a habit.

Signals come in different types: they might be an internal stimulus (say, boredom) or external one (a friend’s message or push notification). We’ll talk more about signals in an upcoming article.

More dopamine facts

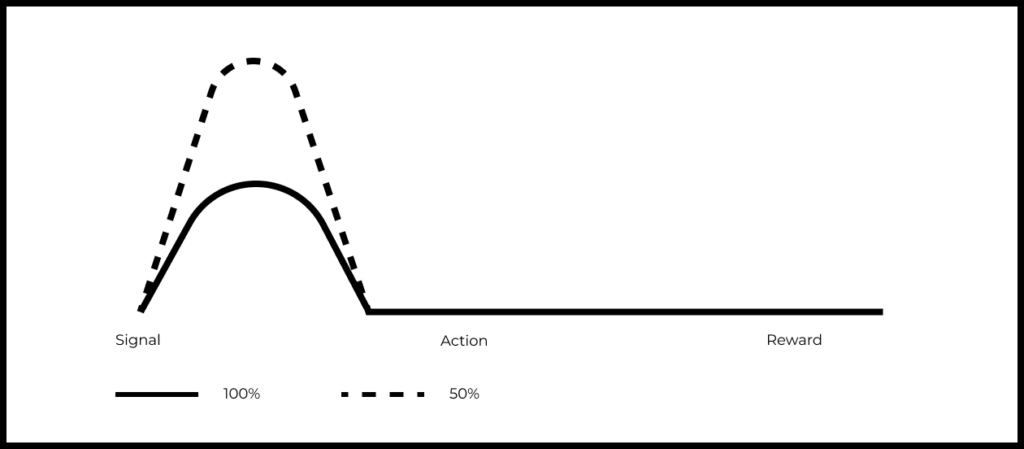

There are a few other things you should know about dopamine. Large bursts of it are generated when it’s hard to predict the likelihood of a reward. In one famous experiment described by Robert Sapolsky, monkeys release twice as much dopamine when the likelihood of reward for an action drops from 100% to 50%.

Doomscrolling is a byproduct of dopamine as well. In one 2020 study, scientists confirmed that even when information does not directly lead to a reward, dopamine will still drive information-seeking behavior. This mechanism works in exactly the same way as if the brain is expecting to receive a reward. In other words, information itself can be the reward.

How products encourage habit formation

With Wordle we saw the basic mechanics of how a habit is formed. The game itself is not complex. Although it starts by giving the player a dopamine rush, the game is monotonous so the amount of dopamine won’t increase over time. Eventually, the player will probably switch to more engaging alternatives that use more complex mechanics to maintain the player’s interest for longer.

Here are real-life examples of how unpredictable rewards stimulate higher dopamine amounts, and therefore increase motivation to perform a habitual action.

Example: TikTok (as a content creator)

When you post on TikTok, there’s no way of guessing your reward: who, when, and how many likes your video will get. The user gets a notification and, with it, a dose of dopamine in anticipation of opening the app. Engagement and frequency of interaction with TikTok grow after posting a video. But if you have only ten active followers and only those ten can see it, you probably won’t be as enthusiastic: it’s too easy to predict the result.

For a dopamine feedback loop to form, the user is prompted to perform an action with the potential to bring a bigger reward. This gets them more motivated to open the app:

- Got 1,000 views?

- What if you participate in this challenge?

- How about trying this sound?

Example: games

Some of the mechanics in casual mobile games, like slot machines, come straight from casinos. MMORPGs add an element of randomness to rewards when the player collects loot from a fallen enemy. Just like with social networks, the sheer unpredictability of the reward inspires the player to return to the game and perform actions that promise such rewards.

These mechanics for engaging users and reinforcing habits need to be recurring:

- I got this awesome item today, but which one will I get tomorrow?

- Will I be able to defeat the new boss?

- What will the next reward be?

Users may not always verbalize these questions, but the process of finding answers—combined with dopamine—will keep them coming back to the product.

Habits are powerful—and potentially harmful

Dopamine plays a key role in forming new habits. As a neurotransmitter, it helps people to remember behavior that leads to a reward, or at least whatever the brain considers to be a reward. A recurring Signal–Work–Reward sequence can make product use into a habit. This makes the user feel attachment and added value on an unconscious or semi-conscious level.

In the next article, we’ll delve into the Hook Model of habit formation created by Nir Eyal, author of “Hooked”.