We discussed in our previous article why it’s important to reduce time to value. The more quickly a new user can experience a product’s added value, the more likely that the user will choose that product instead of the alternatives.

There is a catch, though. The time to value can be reduced only within certain limits. For a hypercasual mobile game, a user might be able to experience value just 30 seconds after opening the game for the first time. But in the case of a task tracker like Jira by Atlassian, a corporate user might need weeks to experience the “aha moment”. No matter how well you streamline the onboarding process, you simply can’t compress those weeks into minutes. In this article we will look at how to approach activation for a product based on its specific level of complexity and time to value.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

All posts from the series

01. When user activation matters and you should focus on it.

02. User activation is one of the key levers for product growth.

03. The dos and don’ts of measuring activation.

04. How “aha moment” and the path to it change depending on the use case.

05. How to find “aha moment”: a qualitative plus quantitative approach.

06. How to determine the conditions necessary for the “aha moment”.

07. Time to value: an important lever for user activation growth.

08. How time to value and product complexity shape user activation.

09. Product-level building blocks for designing activation.

10. When and why to add people to the user activation process.

11. Session analysis: an important tool for designing activation.

12. CJM: from first encounter to the “aha moment”.

13. Designing activation in reverse: value first, acquisition channels last.

14. User activation starts long before sign-up.

15. Value windows: finding when users are ready to benefit from your product.

16. Why objective vs. perceived product value matters for activation.

17. Testing user activation fit for diverse use cases.

18. When to invest in optimizing user onboarding and activation.

19. Optimize user activation by reducing friction and strengthening motivation.

20. Reducing friction, strengthening user motivation: onboarding scenarios and solutions.

21. How to improve user activation by obtaining and leveraging additional user data.

Why time to value is product-specific

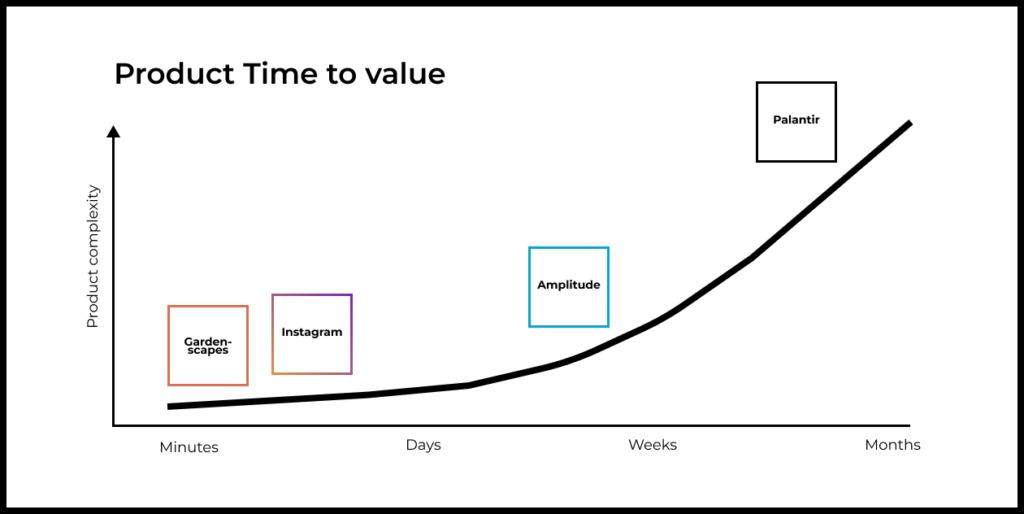

The amount of time needed for new users to experience added value will vary from product to product.

You can (and should!) reduce time to value as much as possible. This is an important lever for improving activation rates, after all. But the time to value for any given product can be reduced only so far.

Take the match-3 casual game Gardenscapes, for example. The journey from launch to experiencing value takes just minutes. The game immediately hooks the user with familiar and intuitive gameplay.

On the other hand, consider the product analytics platform Amplitude. Instead of minutes, the time to value will be measured in days or even weeks. A company curious about the product has to segment and configure events, integrate the Amplitude SDK, roll out a new version, collect data, analyze the data, get insights, and make decisions.

Only after that whole process can the company see how much easier it is to extract insights from data in Amplitude, as compared to relying on an overworked analytics team or combing through intimidating databases.

So for Amplitude, the decision to use the product is inevitably followed by days or weeks before the “aha moment” can happen. There is no way to reduce the time to value to a few minutes.

Perhaps, you object, potential clients could access an Amplitude demo account with dummy data to get a feel for how it works? True, undecided potential users might appreciate this as an additional tool for learning about the product. But a demo account would not give users the opportunity to experience added value for themselves or see the actual benefit for them of investing in learning and integrating Amplitude. And precisely that personal analysis is at the heart of activation.

Every product by its nature has a certain time to value. You can nudge the time to value downwards, but only a little. Once we acknowledge this fact, we can design the activation process to fit the product’s complexity and length of the value journey.

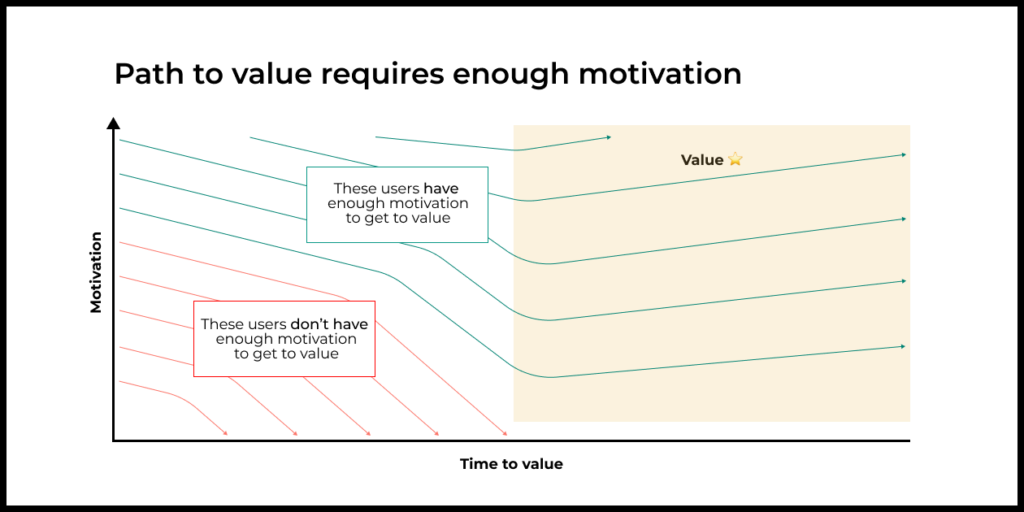

How the user intent threshold depends on time to value

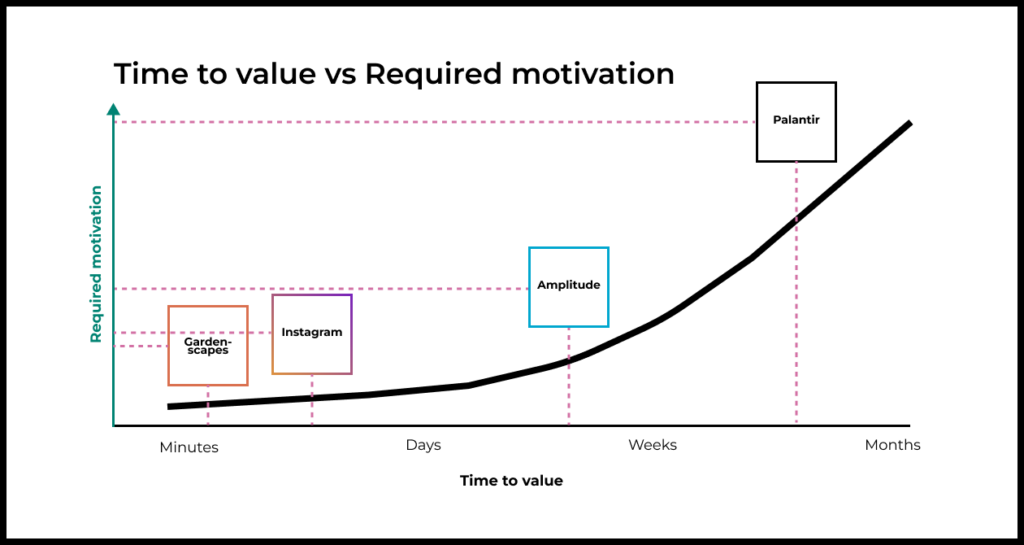

As a product’s complexity and time to value increase, the more motivation and intent your users will need to reach an “aha moment” and appreciate the product’s added value.

Here are a few real-life examples illustrating this.

Why misleading ads worked for match-3 casual games

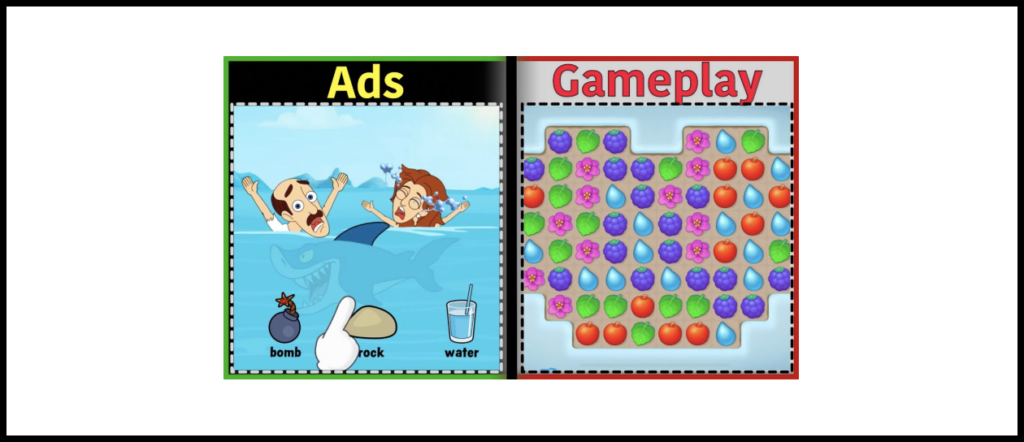

At one point, major game developer Playrix started making ads that featured puzzle mechanics not representative of actual gameplay. Ultimately, such online ads were banned because of their misleading nature.

The point of using fun mini-games unrelated to the game actually being promoted is that Playrix wanted to reach the maximum number of users within that promotional channel. If a (misleading) mini-game is engaging, it is more likely to be shown by ad networks to more users.

Any gains from these mini-games (from improved user acquisition) would have to offset in-product conversion losses (by users who abandoned the game due to unmet expectations). Otherwise, the unit economics would not work for the developer and the ad campaigns would run at a loss.

We can assume that this tradeoff still paid off, judging by the fact that such mini-games and promotional strategies have long been used by other major casual game developers.

But why would an ad demonstrating non-representative gameplay work at all and bring profits to the developers of Gardenscapes and other popular match-3 games?

The biggest match-3 games are very strong products aimed at a mass audience with minimal time to value, good retention, and high lifetime value (LTV). Even users who have come to the product with misshapen expectations can still appreciate the short time to value, simplicity, and fun gameplay. The relatively low intent of users brought in by misleading advertising is still enough for many of them to experience the product’s value and be happy enough to make purchases.

As a product’s time to value decreases, so does the threshold level of intent necessary for a new user to appreciate the product’s value.

Why display ads don’t work for complex B2B products

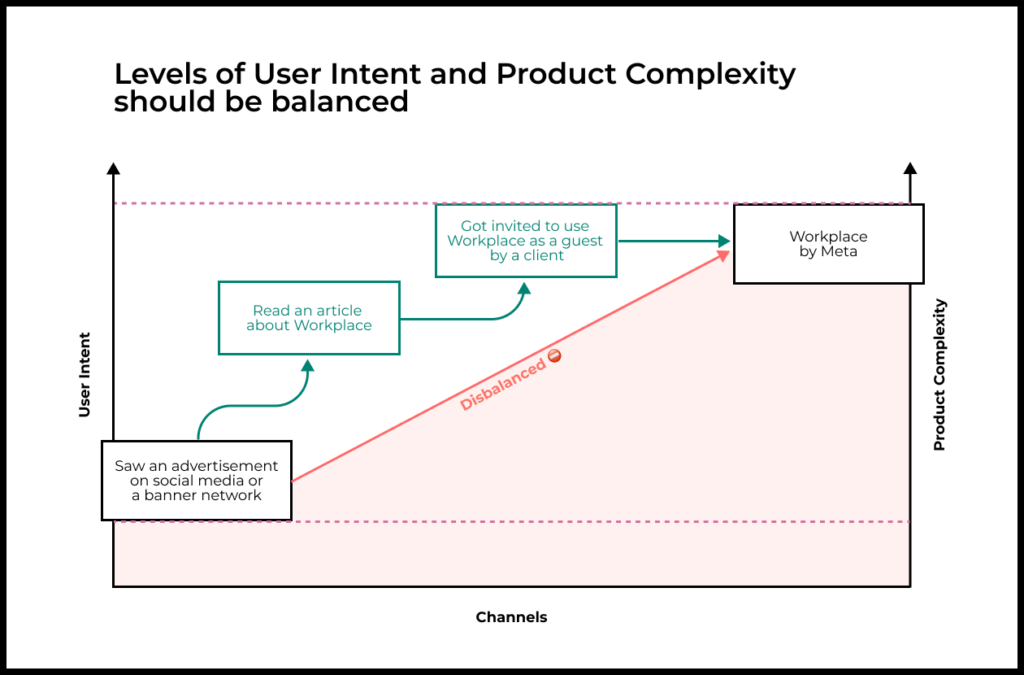

Now let’s look at Workplace by Meta, a rather more elaborate product.

Workplace is a service for company-wide communication and collaboration that has been particularly successful in non-tech industries like banking, insurance, retail, dining, government, and non-profits.

I joined the Workplace team before the public launch and continued working there for three years. For much of that time I was on the team responsible for attracting and activating small to mid-sized businesses.

Our team spent a lot of time and effort trying to attract new companies from our target segment with display ads. We wanted display ads to work so badly largely because it seemed that tools from our parent company Meta (then still Facebook) could crack that channel open for us.

We used both Meta’s ordinary advertising products available to everyone as well as custom integrations with other services used by businesses (Pages, Ads Manager, Groups).

Most of these efforts had so-so results. Companies brought in by display ads would tend to convert 10 to 20 times less often than companies that had come organically.

The thing is that Workplace is a complex product with a long time to value. A company must undergo a considerable journey before finally experiencing value. The first user has to create an account for the company and then convince their colleagues to switch to Workplace from email or another service. Then they have to configure spaces for collaboration, invite colleagues, wait for said colleagues to create accounts, and only then start migrating various use cases to Workplace from other services.

For Workplace to catch on, there usually had to be a very motivated first user with backing from top management. An ordinary employee or mid-level supervisor would not be influential enough to change how their company communicates. These decisions require a champion with a lot of “pull”.

Workplace is a complicated product with a long time to value as well as significant obstacles on the user’s journey to value. The problem, for us, was that display ads by their nature will tend to attract users with low motivation and intent.

Picture a user scrolling through Instagram out of boredom. Suddenly an ad there describes a new way of communicating with colleagues. Some users might be interested in this, but they are not in a setting or frame of mind to start re-structuring communication at their company.

This disbalance—between new users’ level of intent and product complexity—was the main reason why display ads did not work for Workplace. The team might invest years into reducing onboarding friction and shortening time to value, but this still wouldn’t turn display ads into a growth driver. The reality is that for these channels, there was no product/channel fit.

This does not mean that display ads are never useful for promoting complex B2B products, however. Monday∙com is one example. You have probably seen them a few times in YouTube pre-roll ads. For complex products, display ads can be an important tool as part of a broader marketing mix. Such ads build customer awareness and demand that can be later developed with other channels and tools.

Balancing user intent and product complexity

We started this article by noting that every product has an intrinsic level of complexity and corresponding time to value. The examples above show how time to value and product complexity constrain the level of motivation and intent that potential new users coming to a particular product must have. This, in turn, affects the channels available to the team for product growth.

As we saw with match-3 games, simple products can sometimes get ahead even with the help of misleading advertising that draws in less-than-motivated users.

For complex products with a long time to value, we have to structure activation so that users start the in-product onboarding flow only when they are truly ready—with enough motivation and trust—to experience the product’s value.

That’s why sometimes, counterintuitively, it makes sense to add friction at certain stages of activation. This friction will improve timing and give better overall results. Examples might include having to personally contact the sales team for pricing or having to schedule a call in order to test drive a trial version of the product.By understanding a product’s level of complexity, we can select the right mechanisms for drawing in and activating users. These mechanisms need to filter out new users who don’t currently have enough motivation. And if done right, these mechanisms will ensure sufficient support throughout the user journey, all the way from sign-up to the “aha moment”.

Shaping activation around time to value

So as complexity and time to value increase, the more obstacles there are between sign-up and experiencing value. The more obstacles there are, the more motivation, help, and support that users will need to reach an “aha moment”.

It follows that the longer a product’s time to value, the more we should make the process for activating and onboarding new users sophisticated and personalized.

Let’s consider how this might work in the context of a specific product.

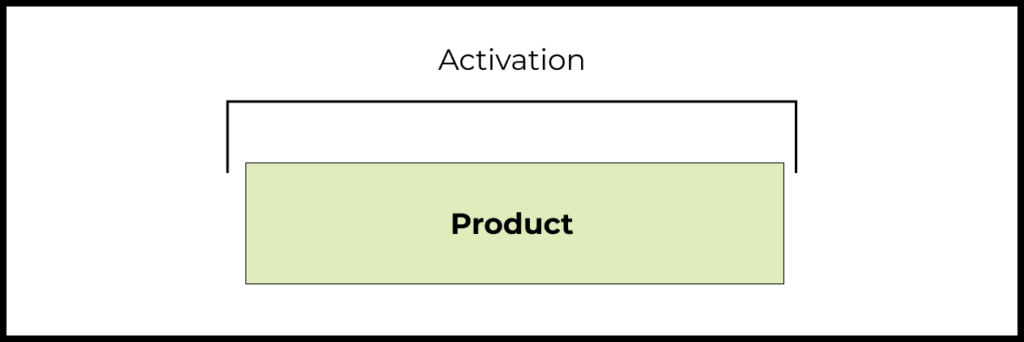

Building blocks for activation in a simple product

For a match-3 casual mobile game, user activation will occur mainly at the product level.

The team will concentrate on structuring the progression of levels within the game, teaching gameplay, integrating the plot, getting the user engaged, and deciding when and how to send notifications to users.

This is the level at which most product managers think about onboarding and activation. But as a product gets more complicated, it becomes harder to boost activation purely through product experience.

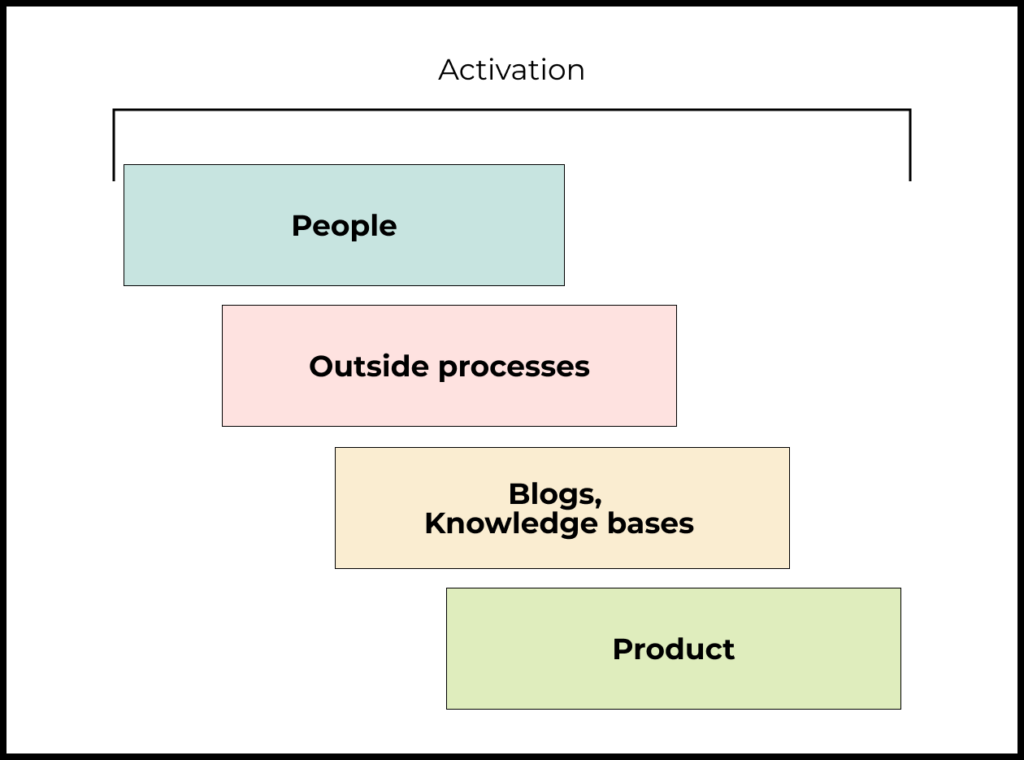

Building blocks for activation in a complex product

For complex products such as Amplitude and Workplace, user onboarding within the product is just one of many components of activation.

Components include the product itself, people (sales team and Customer Success Managers), tutorials and educational materials, a knowledge base, and case studies of successful clients.

User acquisition and the monetization model are also hugely important. They shape the level of motivation and intent of users who encounter the product.

So when designing activation for a complex product, the team needs to keep all these factors in mind to create a system that can find target users through growth channels, build relationships with them, create an awareness of the problem and demand for a solution, and ultimately deliver value.

As product complexity increases, so does the importance of user motivation and supporting users as they move from sign-up to obtaining value. The absence of motivation makes it unlikely that they will persist to see the product’s value. The absence of help sufficient for overcoming obstacles will cause users to drop out at various stages of the activation process.

In an upcoming article we will look more closely at the main types of building blocks for the activation process, and which ones should be used when.

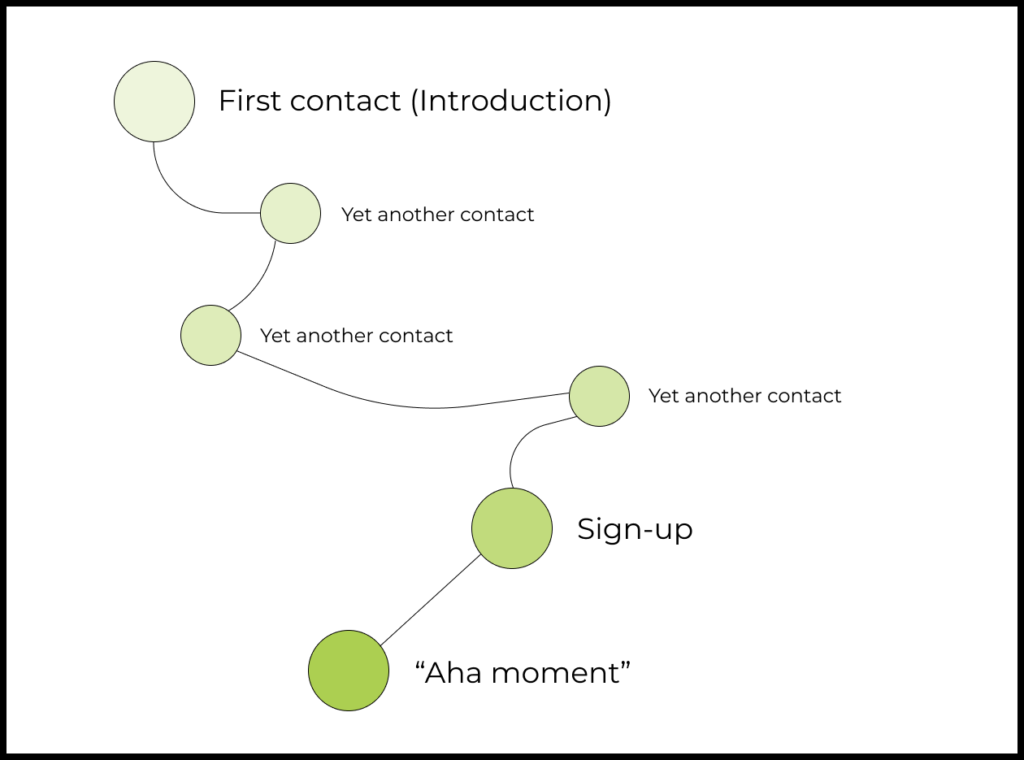

Mistakes in activation for complex products: an example

At Workplace by Meta, the team for attracting small to mid-sized businesses invested vast amounts of time and effort into optimizing activation of new users at the product level.

This investment brought some results, but returns diminished quickly. The key reason was that for complex products, successful activation begins long before sign-up. Activation is much more than just onboarding or a user’s first session with the product. At Workplace, the team was concentrating on just one small piece of a much larger and interrelated system.

To meaningfully improve activation, the team needed to broaden its focus and look at the user’s entire journey, from hearing about the product to the “aha moment”.

Let’s compare two hypothetical users who have signed up for Workplace. Both of their companies can benefit equally from Workplace, but the first users at each company heard about Workplace in very different ways:

- At Company #1, the one to hear about Workplace was the CEO. The CEO heard about it from an old entrepreneur friend, who loves Workplace and has used it for years. The friend casually mentioned how to get the most possible out of the product based on the specifics of the CEO’s company and industry.

- At Company #2, an HR employee happened to walk by a billboard at an airport.

At Company #1, onboarding can start right away. The CEO has both the motivation and authority needed for the company to reach the “aha moment” and see the product’s value.

But if the HR employee at Company #2 starts the onboarding flow as the company’s admin for Workplace, then the company will almost certainly not have an “aha moment”. A better idea might be for the HR employee to learn about the product with a demo account and then help to convince their boss or an influential executive at the company that the product could make the company more efficient. Doing so will take additional materials, case studies, webinars, or a personal call with the sales team. Product-level activation can take place only after all these other stages have been completed.

That’s why for complex products, users should start the onboarding flow only if they already want to use the product and are aware of how it can make their life better. Without trust and motivation, the user will give up before ever seeing the product’s value.

Fitting activation to product complexity and user intent

Every product has its own intrinsic complexity and corresponding time to value. These two things have an enormous influence on the user activation and acquisition mechanisms available to the product.

The higher the complexity and time to value, the more motivation and intent that new users will need. Users should have enough of both to overcome all obstacles and reach the “aha moment”.

The higher the complexity and time to value, the more personal the user activation process must be. Users will need more assistance to overcome obstacles and ultimately reach value.

For mass-market B2C products, in-product onboarding, if done right, may be enough for good activation results. But for more complex B2B products, obtaining similar results may require a very strong brand and dedicated team helping the client to integrate the product into existing processes and obtain value.