In our previous articles, we showed how people change the way they get a job done after finding a new product whose benefits outweigh the cost of switching.

But it’s not enough just to make a product that does the job significantly better. People make decisions based not on a product’s objective value, but its subjective perceived value—how that particular person happens to feel about the product.

People are not always rational in their decisions. This topic has been covered at length by Dan Ariely (“Predictably Irrational”) and Daniel Kahneman (“Thinking, Fast and Slow”). Many different factors affect perception. So when working on activation for your own product, you have to go beyond the objective benefits of the product and also focus on how users see this value, how they come to realize this value, and what factors impact this process.

Below we will expand on why a product’s perceived value can vary from its objective value, provide examples illustrating this discrepancy, and suggest how and why to use this knowledge for improving product activation.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

All posts from the series

01. When user activation matters and you should focus on it.

02. User activation is one of the key levers for product growth.

03. The dos and don’ts of measuring activation.

04. How “aha moment” and the path to it change depending on the use case.

05. How to find “aha moment”: a qualitative plus quantitative approach.

06. How to determine the conditions necessary for the “aha moment”.

07. Time to value: an important lever for user activation growth.

08. How time to value and product complexity shape user activation.

09. Product-level building blocks for designing activation.

10. When and why to add people to the user activation process.

11. Session analysis: an important tool for designing activation.

12. CJM: from first encounter to the “aha moment”.

13. Designing activation in reverse: value first, acquisition channels last.

14. User activation starts long before sign-up.

15. Value windows: finding when users are ready to benefit from your product.

16. Why objective vs. perceived product value matters for activation.

17. Testing user activation fit for diverse use cases.

18. When to invest in optimizing user onboarding and activation.

19. Optimize user activation by reducing friction and strengthening motivation.

20. Reducing friction, strengthening user motivation: onboarding scenarios and solutions.

21. How to improve user activation by obtaining and leveraging additional user data.

Mechanisms for improving perceived value: individual perception

Everything is relative. Human perception is imperfect. These two facts can cause plenty of situations in which people perceive value in very non-objective ways.

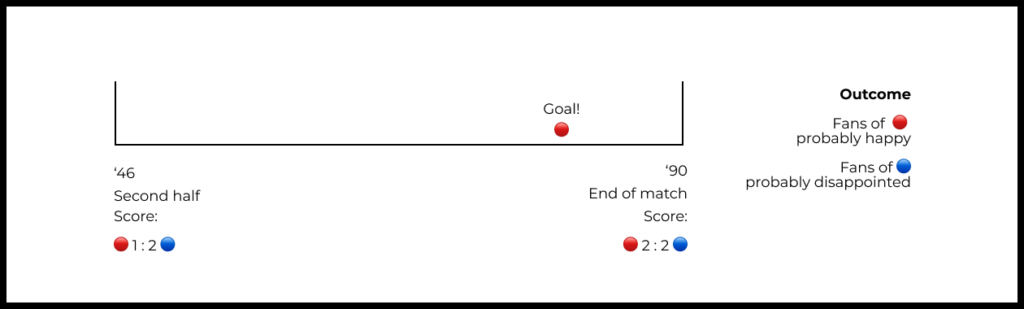

Example: A tied soccer game

Two soccer teams have finished their game in a tie. Imagine the reaction by fans if their team has just scored a goal during the closing minute. By contrast, imagine that their star forward has missed a shot, costing the team victory. The final tie score (the objective value) is the same in both cases, but the perception will be extremely different.

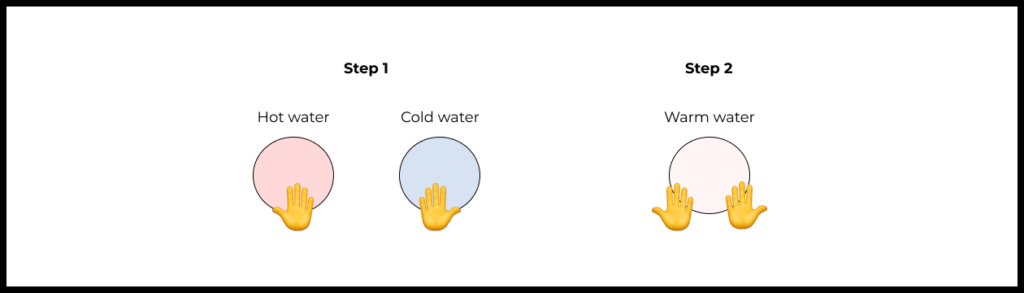

Example: Hot and cold water

Sometimes it’s possible to feel the difference between objective and perceived value very quickly and memorably. Put one hand in a tub with hot water and your other hand in a tub with cold water. Then try putting both hands in the hot water—your hands will feel quite different.

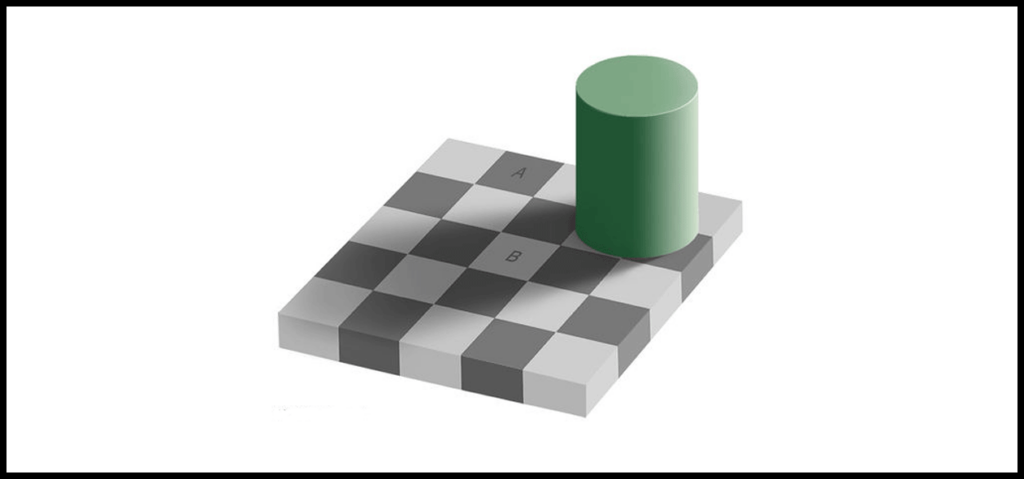

Example: An optical illusion

Most people think that squares A and B below are different colors. But objectively, they’re the same color. (Check for yourself using any graphics editor of your choice.)

Often it’s impossible for someone to identify and analyze all the factors needed to make a “rational” decision. This is especially true in new and unfamiliar situations when the key factors aren’t even known. This also applies in situations that are emotionally charged.

In the absence of a pre-existing template, people start making judgments based on weaker signals: other people’s behavior, indirect evidence, abstract principles, or comparison with the available alternatives. Emotions tend to push out our rational thought processes. Because of this, the value we perceive might not be what objectively exists.

Let’s look at a few of the kinds of situations when our cognitive wiring causes perceived value to differ wildly from objective value.

The importance of indirect evidence

Example: Painkiller experiment

Researchers at MIT in Boston wanted to test a new experimental painkiller in humans.

They invited subjects into a waiting room where they had placed brochures about the painkiller. Then they connected each subject to a machine that generates electrical shocks. After each round of shocks, the subject would rate their pain on a computer. The subject received the painkiller before going through another round of electrical shocks and rating their pain again.

But they weren’t receiving any painkiller at all, actually. They received just a placebo—a simple vitamin C pill. The difference between the groups was in the brochure they got. The first group’s brochures said that the eventual retail price of the medication would be $3 per pill. The brochure for the second group gave a price of just $0.10.

Although the objective effect of the pill was unchanged, the group with the higher price perceived more value. In the group receiving $3 pills, 100% reported relief. But only 50% of subjects in the 10-cent group had their pain reduced after taking the same vitamin C placebo.

This is a clear case of the placebo effect, when relief comes not from pharmaceutical properties but from the patient’s belief and state of mind. In this experiment, higher prices increased the effect of the “painkiller”.

Thus pricing itself influences a product’s perceived value. There is a common assumption, drawn from experience in other areas of life, that effective, high-quality products cost more. Test subjects subconsciously applied this assumption during the MIT experiment.

A similar effect is at work when reviews and ratings by other people affect our decisions. When we make a choice involving an unfamiliar topic or complex products, an independent expert’s opinion can play a decisive role.

Example: Street violinist

Now picture a busy subway station with an ordinary-looking street musician playing on a violin near the entrance. If they were actually one of the world’s greatest living violinists, how much money do you think passersby would leave?We know the answer thanks to an experiment performed in Washington D.C. by violin star Joshua Bell.

By the numbers:

- Performing for 60 minutes during rush hour, he collected a total of $32.

- 98% of passersby did not pay any attention to him.

- Only 2% left any money.

- Less than 0.5% lingered to listen (many of the lingerers recognized Bell).

These earnings weren’t much more than an ordinary busker would have made. The commotion of a noisy subway setting brought a star down to the level of a ho-hum street performer, even though his playing was as masterful as ever.

People aren’t able to objectively assess mastery or quality in many fields. The setting and context are enormously important for preparing their perception.

Example: A tale of two developers

Picture that two developers have come to you for a job interview. There is no difference between them and they have the exact same skill level (objective value). One of them previously worked at an industry leader, while the other was at a failed startup.

The first candidate will usually have greater perceived value, even though their objective value is the same.

How is this actionable in practice?

Determine the signs and factors that people use to indirectly measure your product’s effectiveness and quality. Then think about how this knowledge could help you to impact perceived value.

Scarcity effect

Another way for boosting perceived value is to create scarcity and competition for a limited resource.

Example: Clubhouse

Remember the battle for Clubhouse invites? The product creates value because of the ability to listen to discussions with interesting people, but invitation-only access multiplied this value in the eyes of users who wanted to be part of the action. A prime case of Fear of Missing Out (FOMO).

Example: Snapchat Spectacles

In September 2016, Snap launched sales of the company’s Snapchat Spectacles. But instead of selling them online, Snap decided to install unique vending machines in random places. People shared these locations with each other on social media and lined up for the choice to snag a pair. Snap played on the audience’s FOMO and artificial scarcity.

Something similar happens with people buying limited edition sneaker collections, catching a flash sale, or applying to prestigious universities.

How is this actionable in practice?

Even if your product is a digital one, you can still create artificial constraints that will increase its perceived value. This could involve selectivity: handpick users through an application process, add users by invitation only, or offer special privileges to qualifying users.

Don’t get carried away though—hype alone won’t get any product far. It’s still as critical as ever for the product to create sufficient added value and solve a real job-to-be-done.

Confirmation bias

People often confuse correlation and causation. Product teams are no exception. This confusion, combined with selective cherry-picking of facts, leads to confirmation bias.

We want to see positive trends in things that are important to us, like our health. But it’s a mistake to automatically assume that any improvement is because of something we’ve done.

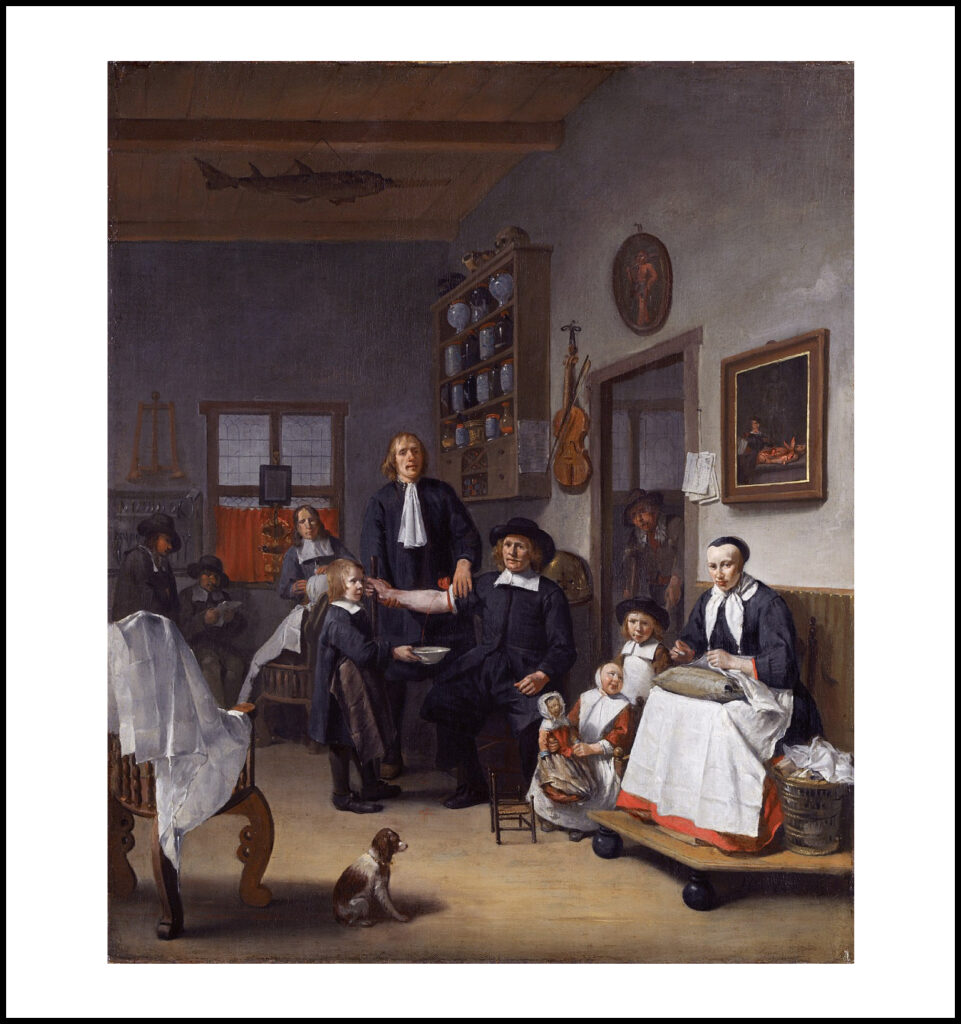

Bloodletting was pretty common centuries ago, after all. This action had no benefit at all for patients. Still, most patients survived. Therefore, people assumed that bloodletting must have been why, mixing up correlation and causation as they did so. They incorrectly perceived bloodletting as having value. As a result, it was used actively despite having no objective value for patients.

There are countless such examples around us even now. The predictive value of astrology, say, is zilch, although many people would not agree. This too is the result of confirmation bias: people think that random-but-correct predictions mean that astrology “works”.

Product teams make this same kind of mistake when they analyze the success of other products and try to apply it to their own. For example, a product manager decides that a popular product became successful because of a certain feature, so they decide to add the same feature to their own product. However, making this kind of decision requires knowing the wider context and the added value that the feature would have in your product compared to your competitors.

This thinking can also work in the opposite direction. Some people might perceive an effective product as harmful or ineffective because of isolated incidents. You can hear anti-vaxxers, for example, discount the experimentally proven (objective) effectiveness of a vaccine because of perceived risks based on one-off anecdotes or conspiracy theories.

How is this actionable in practice?

Alas, this cognitive glitch is usually used to cause harm, either to defraud people by selling them products that don’t work or to discredit products that actually are good. What you can do is find the patterns in how people come to their conclusions about product value, whether right or wrong, and try to minimize wrong ones.

Impact of brand on perceived value

Branding and positioning are also important for perceived value.

Example: iPhone and Android

When deciding whether to buy an iPhone or Android smartphone, not all buyers will bother comparing tech specs. An iPhone can be preferable sheerly thanks to brand. Here again we see the power of indirect evidence, with a more expensive iPhone likely to be perceived as a worthier purchase.

Something similar makes people sure that the latest iPhone always has the best camera on the market, even if there are Android alternatives with better optical characteristics.

Example: Telegram and WhatsApp

Telegram built a brand as the most secure and private chat platform. The thing is that objectively, WhatsApp—with end-to-end encryption for all chats, and no server-side storage of messages—beats Telegram on both counts.

Ordinary chats on Telegram are stored on the company’s servers. Users wanting a level of security and privacy comparable to WhatsApp have to manually create secret chats, which most users have no idea about.

But most people who use Telegram have the impression that it’s more secure than WhatsApp.

(In this specific example, WhatsApp is also hurt by the brand of its parent company Meta, considering the latter’s association with use of personal data for advertising purposes.)

How is this actionable in practice?

You can use positioning and brand to increase perceived value. This works particularly well if your brand is built in opposition to a major competitor that lags behind you in that particular aspect in user opinion.

Emotion’s importance for perception

A strong emotional reaction can change how we perceive reality.

People are more afraid of flying than driving. Of course, all the statistics say that airplanes are the safest mode of transport.

When swimming, we tend to be more afraid of sharks than of drowning. This is an emotional reaction that is contradicted by the evidence.

This is why those promoting propaganda and populism often aim for “gut reactions”. Emotional resonance shuts out all rational argument.Emotions are an important part of how users form and reinforce product habits. When a product causes positive emotions, the user is likely to overestimate their benefit from it and becomes more reluctant to abandon the product or switch to an alternative. For details on the theory and practice of habit formation and the importance of dopamine for products, read our series of articles.

How is this actionable in practice?

Identify the situations when your product sparks strong emotions. These moments can be a great opportunity for forming a positive perception and, potentially, a product habit.

User expectations

Example: Antivirus software that’s too fast

The team for one antivirus app put a lot of effort into making the virus scan process on smartphones as quick as possible. They reduced this time to just seconds. And this, the team thought, was the product’s added value compared to the alternatives.

The problem was that after they launched the new version, conversions (purchases of the full version) fell substantially. In-depth interviews showed that people didn’t believe a legitimate antivirus app could scan for malware that quickly. The team confirmed this hypothesis when they artificially increased scan times.

Example: Instagram’s algorithmic feed

Something similar occurred when Instagram launched an algorithmic feed. The point of the algorithmic feed was to solve a problem: many Instagram users have much more new content than they are able to view on an average day. This kind of feed was designed to show the user what is most likely to interest them.

All of the Instagram team’s experiments showed a positive effect for user engagement. Key user metrics all improved considerably. But a large number of users were still unhappy with the algorithmic feed.

In 2016 Instagram ran an experiment where users could try out the algorithmic feed. When told that the feed was just an ordinary one, people liked it. But they became unhappy after learning that it was algorithmic.

How is this actionable in practice?

Try to identify your users’ expectations of the product and determine how well the product fits them. If the product does not act in the way they expect, this will be a signal for many users that the product does a bad job, even if the facts say otherwise.

Mechanisms for increasing perceived value: communicating value

So far we have been describing the mechanisms that impact perceived value at the level of individual perception.

But there are other types of mechanisms as well, most of them at the product level.

How product value is communicated

Simply presenting information in a different way can improve your product’s perceived value.

Example: Joom and Wish

Many users of Joom, a cross-border marketplace, revealed during interviews that they preferred Joom over its direct competitor Wish because Joom offered free shipping.

Actually, the cost of shipping was nearly identical on Joom and Wish. The difference is that on Joom, the cost of shipping was included in the product price. Wish showed the “clean” price and only added shipping during checkout.

This is another case where the objective effectiveness (in this example, the final checkout price) was the same but Joom was perceived as cheaper thanks to not adding separate shipping charges.

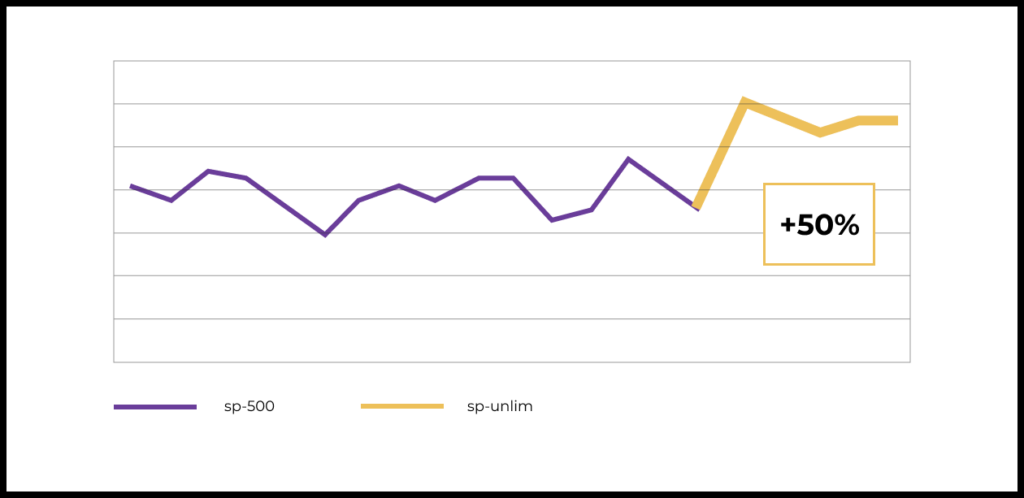

Example: Cut the Rope

Another example comes from the mobile game Сut the Rope.

The developer made a tiny change. In the game store, they increased the quantity in the fourth pack of superpowers (a paid add-on for easily completing a difficult level) from “500” to “infinite”.

In practical terms, nothing had changed. Having 500 superpowers was easily more than enough for completing the game—this far exceeded what the user could ever possibly need. But the change sparked a 50% revenue increase for the pack. Buying an unlimited amount of superpowers is just nicer.

How is this actionable in practice?

The same value can be communicated in different ways inside the product. Find ways of presenting value so that users see as many distinct and tangible advantages as possible.

Talking about technical benefits vs. what they mean for the user’s life

Example: Saving time with train commutes

The objective value of choosing a train to commute to work, compared to other means of transportation, could include time savings or the opportunity to work on the train. But when communicating with potential passengers, the ways they could spend that time—such as with family—will likely resonate most of all.

Example: Unlimited virtual cards from banks

A bank might highlight their support for issuing an unlimited number of one-time virtual cards. But for users, the much more important upshot is that they can make online purchases more securely. One-time card numbers make it much harder for criminals to perform unauthorized transactions.

Example: Oura

The objective value of an Oura ring compared to the alternatives lies in superior sleep tracking. Presumably this is because the Oura team prioritizes this capability. But in its marketing, Oura doesn’t talk about how precise its sleep measurements are. Instead they focus on how they use such data to help people sleep better and be more productive.

How is this actionable in practice?

Product teams invest a lot of energy in making their product solve user problems more effectively. They tend to use metrics and other quantitative systems to gauge success. But when communicating with users, they can often improve perceived value by accentuating improvements in important parts of people’s lives (“what”), as opposed to mere product features (“how”).

First experience with the product

Example: Markkula’s third principle

Mike Markkula, one of Apple’s first employees, wrote a paper called “The Apple Marketing Philosophy” with three main points, the last of which was:

“People DO judge a book by its cover. We may have the best product, the highest quality, the most useful software, etc.; if we present them in a slipshod manner, they will be perceived as slipshod; if we present them in a creative, professional manner, we will impute the desired qualities.”

Everyone has been in situations when we later revisited our first impression of someone or something. But the first impression of a product is enormously important for perceived value. Overcoming a bad first impression is very, very difficult.

How is this actionable in practice?

We’ve already discussed the importance of tracing the path from when a user learns about the product to when they have an “aha moment” with it. It is just as important to figure out which factors impact user perceptions and make the relevant adjustments.

Ability to surface value

When your product offers many different kinds of value to users, it can be harder to surface the specific value needed by any one particular user.

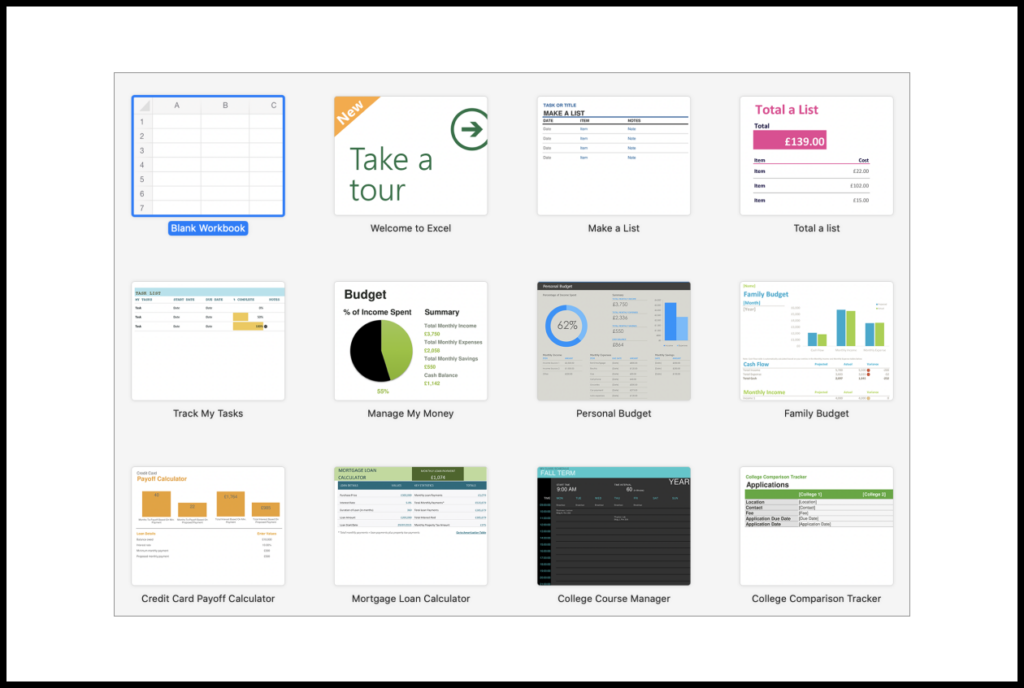

Example: Microsoft Excel

Excel has thousands, if not millions, of use cases. Guessing what a particular user wants to get out of it is nearly impossible.

You can provide templates as a way of suggesting how to use the product. But the user-perceived value of the product will inevitably fall short of the full potential.

This is a common problem for “horizontal” products that ordinary people can use for countless different tasks. Unfortunately, there is no perfect solution for these situations.

Another version of this situation occurs when people see the product differently than the team itself does. People might misunderstand or underrate an important part of the program. Like if users think that a product’s content has been written by other ordinary internet users, but in reality comes from licensed physicians. Or they might not be aware of useful functionality currently available in the product.

These are clear signals of a gap between perceived and objective value. Talking with users is good for catching problems when they describe your product differently than you do.

The perceived vs. objective value gap also applies when a product is used for unintended purposes. For example, a car manufacturer might create a hot rod that brims with speed, maneuverability, and style. But some buyers want one merely for the sake of acquiring a status symbol.

How is this actionable in practice?

You may eventually realize that the product value seen by users doesn’t look like what its creators have envisioned. By keeping an eye on this dichotomy and making timely product decisions, you can reduce this gap—or even turn it to your advantage.

Methods for researching perceived value

There are only so many ways to study users. For looking into product perception and the causes of particular actions, the tools in our arsenal are qualitative ones: in-depth interviews, surveys, and UX testing.

The study design will depend on the product and its job. Below we will just highlight some of the things worth paying special attention to.

Learn what users say about the product

When talking with users, listen carefully to how they describe the product’s value, why they choose it over the alternatives, and what was the trigger for them to start using it.

Direct quotes often contain insights into how users see the product’s value. Using this same language (sometimes even the exact same words) in your own communications can enable more users to appreciate the value of your product.

Track how product perception changes between discovery and the “aha moment”

Another useful approach is to track how user perceptions change between when they learned about your product for the first time to when they realized that it makes their life better.

You’re looking for their subjective impression, not their “objective” or “balanced” opinion. User perceptions can change remarkably over time. But tracing the events that led to those changes will suggest levers for improving perceived value.

Make and check hypotheses

It can be helpful to generate hypotheses about the factors impacting perceived value and test them with experiments and research. For coming up with hypotheses, simply consider the examples above or draw on experience from your own product domain.

Conclusion

Product teams have to be rational as they look for ways to accomplish user jobs more effectively. But when working to improve activation rates, we have to understand how objective value transforms into perceived value at the level of individual users.

Users frequently base decisions on their perception of a product, not its objective qualities.

That’s why it’s important to remember how perceived value can differ from a product’s objective value. Spotting the key levers for increasing perceived value, and learning how to work with these levers, is an important part of the activation toolkit for product teams.