Session analysis is a powerful method for improving the activation process. It allows looking at the product from the perspective of a specific user and observing their journey inside it, from the moment they open it for the first time to when they recognize the product’s value and convert.

Here we will discuss how to use session analysis for designing activation and examine several case studies involving real products.

→ Test your product management and data skills with this free Growth Skills Assessment Test.

→ Learn data-driven product management in Simulator by GoPractice.

→ Learn growth and realize the maximum potential of your product in Product Growth Simulator.

→ Learn to apply generative AI to create products and automate processes in Generative AI for Product Managers – Mini Simulator.

→ Learn AI/ML through practice by completing four projects around the most common AI problems in AI/ML Simulator for Product Managers.

All posts from the series

01. When user activation matters and you should focus on it.

02. User activation is one of the key levers for product growth.

03. The dos and don’ts of measuring activation.

04. How “aha moment” and the path to it change depending on the use case.

05. How to find “aha moment”: a qualitative plus quantitative approach.

06. How to determine the conditions necessary for the “aha moment”.

07. Time to value: an important lever for user activation growth.

08. How time to value and product complexity shape user activation.

09. Product-level building blocks for designing activation.

10. When and why to add people to the user activation process.

11. Session analysis: an important tool for designing activation.

12. CJM: from first encounter to the “aha moment”.

13. Designing activation in reverse: value first, acquisition channels last.

14. User activation starts long before sign-up.

15. Value windows: finding when users are ready to benefit from your product.

16. Why objective vs. perceived product value matters for activation.

17. Testing user activation fit for diverse use cases.

18. When to invest in optimizing user onboarding and activation.

19. Optimize user activation by reducing friction and strengthening motivation.

20. Reducing friction, strengthening user motivation: onboarding scenarios and solutions.

21. How to improve user activation by obtaining and leveraging additional user data.

How to perform user session analysis

Analyzing sessions boils down to three steps:

- Find a user session that you want to analyze.

- Export all of the user’s events, in chronological order, from your analytics system. You can optionally organize events by session and/or enrich them with other data that you have.

- Look (in the literal sense, with your eyes) at how the user interacts with the product.

This profound attention to a specific user’s experience in your product gives a completely different perspective and understanding than you would with aggregated data. You can feel what difficulties the user has, when their first session ends, whether or not they understood the product by then, how long it takes for them to return and why they return, and much more.

Session analysis can be used for different reasons. In this article, we will focus on how to use session analysis for designing the activation process.

Using session analysis to inform activation

In the context of activation, session analysis offers a way to study the behavior of two groups of users:

- People who have succeeded with the product

- People who have decided not to use the product

Usually you will want to know about their first days or weeks (depending on the time to value) with the product.

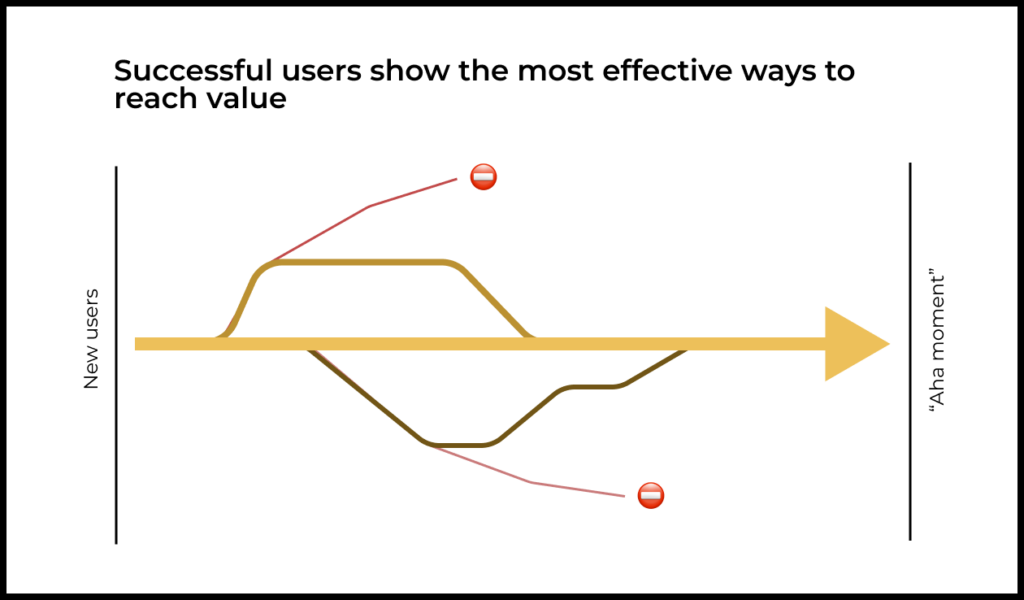

By analyzing the sessions of successful users, we trace the path from first exposure to understanding the product’s value and forming a habit. This analysis reveals the well-trodden paths that enable delivering value and activating users most effectively.

Analysis of the sessions of unsuccessful users reveals the most common dead-end paths. This information suggests where your activation mechanisms aren’t working and you need to make changes.

In most cases, looking at the paths taken by 30–50 users from each of those two groups is enough for a team to sketch out the main paths taken by new users in the product. The team can then see which paths “work” and which don’t.

This work lays the foundation for later work for connecting the anchor points of the user activation journey, leading users to the “aha moment” once the necessary conditions for each use case have been met.

This can also be useful for better understanding and clarifying the criteria for what enables users to see and appreciate value (in other words, achieve an “aha moment”) and what prerequisites have to be true for that to happen.

Using session analysis to rethink user activation for a mobile game

Disappointing launch numbers for King of Thieves

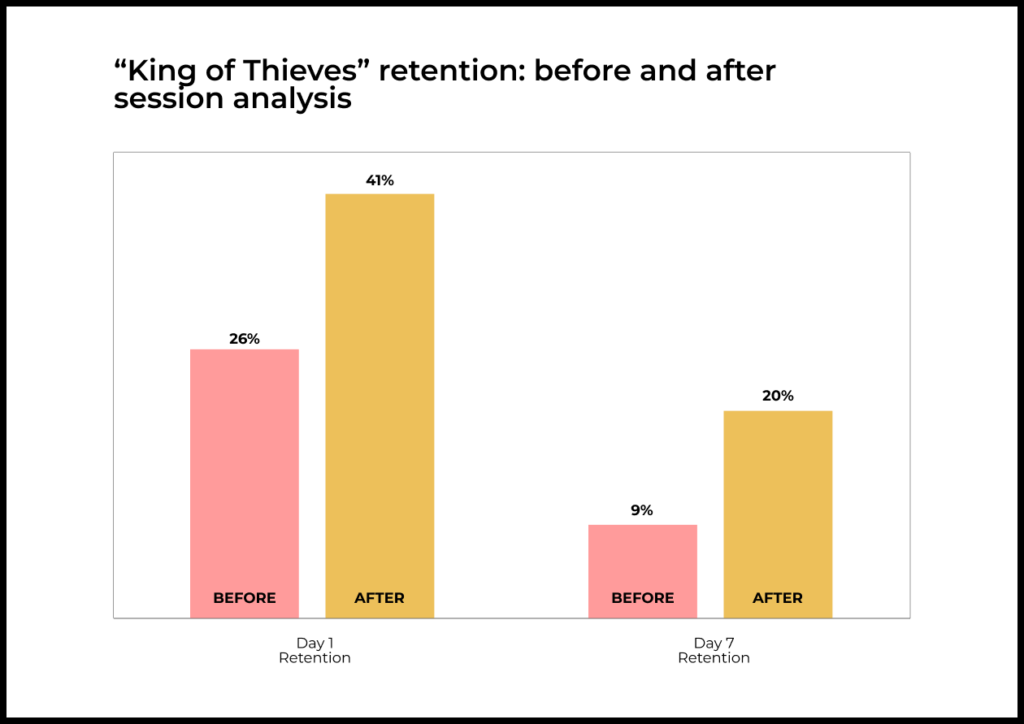

The first version of the mobile game King of Thieves launched with a thud. People weren’t playing and abandoned it almost immediately. The metrics showed big trouble. Day 1 retention was just 26% and Day 7 retention a mere 9%. Compared to other products in this category, these numbers were abysmal.

As we have mentioned, there were two potential causes for such poor metrics: either the product didn’t have value, or else the team had failed to build mechanisms able to articulate this value to users.

Indicators pointed to the second cause. The game had been under development for more than a year and all that time the whole company (including employees from other teams not working on the game) had continued playing it for fun. This gave hope that there was value after all, but perhaps they were just failing to help users see it.

Session analysis of successful and unsuccessful users

To find the causes of this launch failure, the King of Thieves team analyzed sessions for successful and unsuccessful users. They quickly spotted a difference between these two user categories based on their behavior at the start of the game.

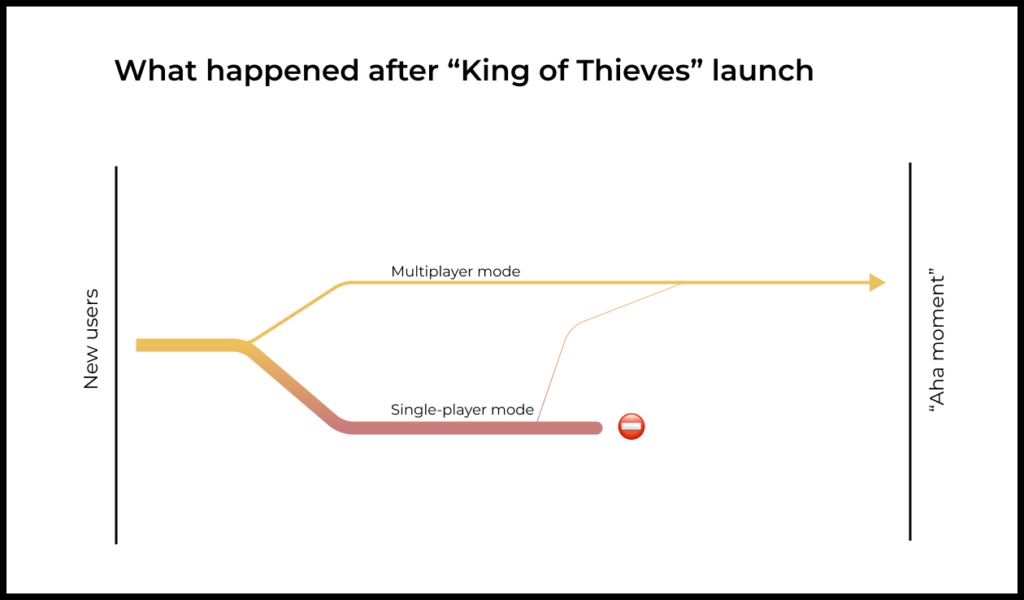

The team discovered that almost all the successful users quickly made their way to multiplayer mode and successfully stole a gem from another player there. Many of these players themselves got robbed of the gem later on. This was the point when they started having a good time and understanding the game—in other words, the “aha moment”.

Simply put, the game is about attacking other people’s dungeons and competing for gems. When designing the onboarding flow, the team assumed that users would need to first learn gameplay in simple single-player levels. Then, the logic went, these users would eventually transition to multiplayer once they had nailed down their skills and felt more confident.

But what actually happened is that most users, after onboarding, continued progressing in the single-player campaign level by level and never paid any attention to multiplayer. Eventually they got stumped by a difficult level or simply got tired of the game, and left.

A few users still tried out multiplayer, but for them it tended to be just like the single-player campaign. Most of the opponents these players attacked did not have any gems to steal. And the ones who did had difficult dungeons, making it hard to steal gems.

After analyzing sessions of hundreds of users (sessions were very short so this didn’t take long), the team had a working hypothesis of what was wrong.

Subsequent “classical” analysis of the data showed that:

- Less than 40% of new users tried multiplayer mode at all.

- Less than 10% of new users successfully attacked another player.

- Less than 3% of users successfully stole a gem from another player.

Of course, the team probably could have found this problem just by looking over the metrics—they could have seen that people weren’t going for multiplayer and even the ones who did weren’t stealing any gems. But the team didn’t know what to look for or where to focus. There could have been other reasons, like people simply not liking the game’s mechanics.

By analyzing sessions and looking at the product through users’ eyes, the team quickly found a discrepancy between the experience of successful and unsuccessful users. Or, more specifically, between real-world player experience and the designers’ initial vision of the game.

Finding solutions with session analysis

Session analysis showed both effective and dead-end paths to value.

This information inspired the decision to re-design the initial user experience with the product:

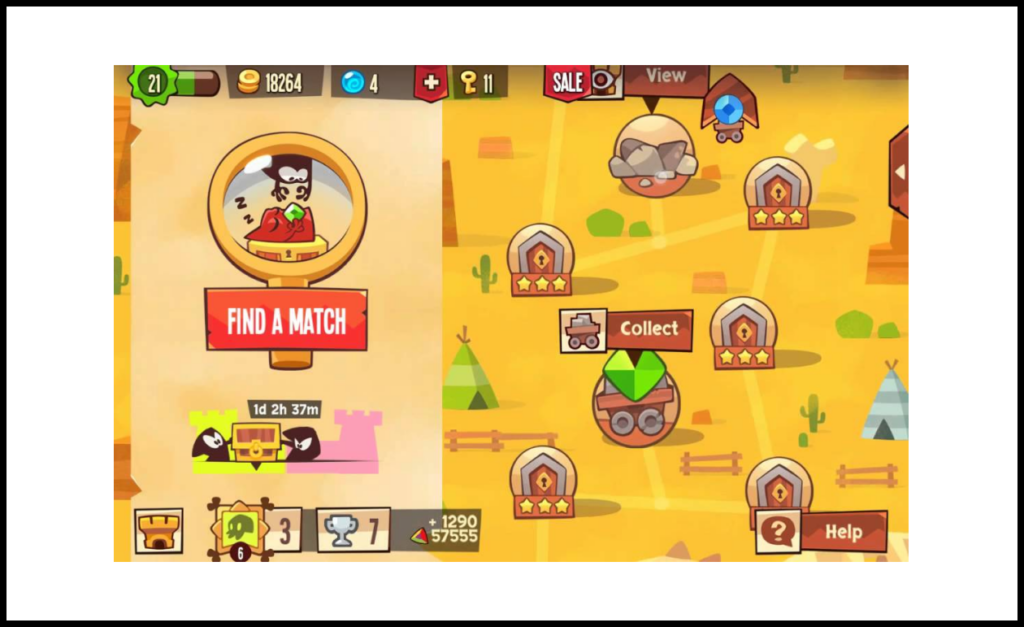

- During onboarding, all new users immediately went to multiplayer and attacked an opponent.

- This opponent (who was not an actual human, but users didn’t know this) would always have gems and the dungeon layout was simple enough that a new player could complete it.

- After a successful attack, the user got a gem and added it to their vault. They rose closer to the top of the leaderboard.

- Soon after, the just-robbed opponent would attack the player and take back the gem.

The first session was now designed in a way that guided people through the core game action, acquainted them with gameplay, and most importantly gave a sense of fun, adventure, and competition with other players.

Dead ends at the start of the user experience were fixed as well:

- Now the single-player campaign was optional. Users were taken to multiplayer right away.

- For those who still wanted to play solo after onboarding, a special animation was added to draw attention to multiplayer.

- The multiplayer option was made more visually prominent.

- Many other decisions helped to simplify the journey to value: the difficulty of the dungeons of early opponents was reduced, the chance of winning a gem after a successful attack was increased, and much more.

Thanks to these changes, the percentage of people experiencing an “aha moment” soared from 3% to 90%.

Day 1 retention grew from 26% to 41%. Day 7 retention also increased, from 9% to 20%.

The game’s value had not changed, but the ways used by the team to surface it to new users certainly did.

Limitations of session analysis

This method of session analysis has a few limitations that are important to keep in mind:

- Firstly, you do not always know the user’s use case, which makes it hard to analyze the user’s actions and assess their journey in the product.

- Secondly, many important events for a number of products occur outside of the product itself. These events will not be reflected anywhere in analytics or data.

Now let’s look more closely at how these limitations might affect decision-making for Workplace from Meta, the corporate communication platform.

Example of the limitations of session analysis

Workplace from Meta is a complex product with many different use cases. The product’s value for users can vary wildly from company to company:

- For some companies, Workplace informs teams about important news, in addition to facilitating discussion and feedback.

- For other companies, Workplace is an environment for collaboration and teamwork on projects and other tasks.

- And at still others, it’s a space for socializing on non-work topics.

Each of these use cases has a different optimal path for realizing value. If you lead users needing collaboration down the path that works for those wanting to socialize with teammates, the result will be far from optimal.

For session analysis it’s important to know what problem a specific user has come to solve, as well as how well their journey in the product fits that use case.

Another difficulty in applying session analysis at Workplace was that much of the process for deciding whether or not to use the service took place outside of it.

These could be discussions over email or in person, for example. A specific employee or team might be the blocker. The problem could also be with the security team. Or maybe a detailed comparison vis a vis the competition pointed away from Workplace.

None of these things are reflected in the data, making them invisible to session analysis. Analyzing just the data we have about product use and success/failure factors will not give a full picture of what caused what.

This doesn’t make session analysis pointless. All it means is that sometimes you will need additional tools to get the job done.

How to compensate for the limitations of session analysis

To solve these problems, it’s often a good idea to combine session analysis with qualitative methods. This extra context helps to see not only what the user does in the product, but understand the bigger picture: what the user is thinking, what they are comparing the product to, what they are trying to do, and what additional actions they are performing outside of the product.

This could be in-depth interviews for insight and context on the actions you see in your analytics system. It could come in the form of hallway testing or usability tests, where people comment on what they are doing and how they understand what is going on. Sometimes a survey might provide necessary information.

Qualitative research combines with session analysis for a full picture of what is happening and points to the key factors shaping the user’s understanding of the product. This foundation is usually enough to form a rough mental model of how the user views the product’s added value.

Using session analysis to improve user activation

Session analysis is a powerful tool for teams wanting to refine activation.

Studying the first sessions of successful and unsuccessful users can identify both effective and dead-end ways of articulating product value.

However, session analysis has two key limitations to keep in mind:

- First, when you’re doing session analysis it’s not always possible to identify the user’s use case, even though it is key to activation.

- Second, the analytics system will have only a fraction of the information needed to measure how well user activation is working. Many things happening outside of the product can have a large impact on the outcome.

To overcome these limitations, round out session analysis with qualitative research.